This post is part of the Tax Policy Center’s new series, Tax Line, which digs into the data behind the day’s most pressing tax policy issues. You can read all posts in this monthly series by clicking on the topics tag, TaxLine, at the bottom of this post.

Since the late 1990s, the earned income tax credit (EITC) has been among the largest federal programs exclusively benefiting low- and moderate-income working families. Designed to encourage work while reducing poverty, the credit grows proportionally with a worker’s earned income up to a cap that varies with family size. The credit then plateaus and falls until it phases out completely at middle-incomes.

According to new estimates from the Tax Policy Center, the lowest-income 40 percent of taxpayers receive almost 87 percent of EITC benefits. Recipients in the bottom 20 percent see an average benefit greater than their federal tax liability – which is paid out as a tax refund.

The effect of the credit is not distributed equally across people with the same income. Larger families receive larger credits. And workers with children – whether married or unmarried – benefit much more from the EITC than those without. This disparity has prompted calls for reform.

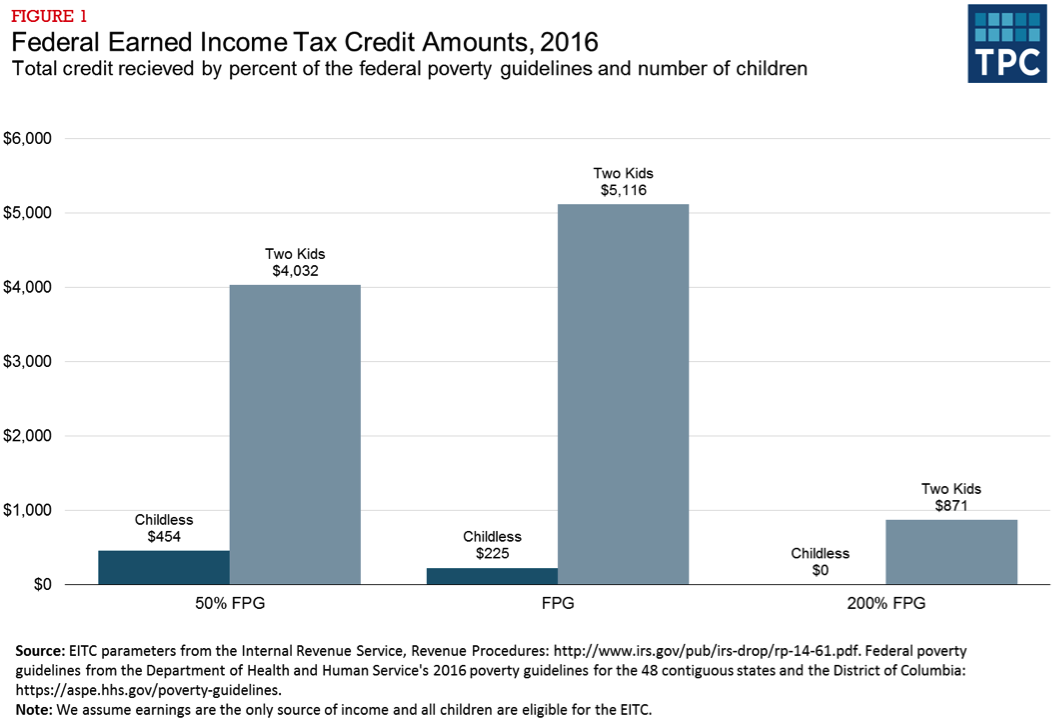

The size of the EITC benefit is closely tied to the number of eligible children in a household. Using the US government’s federal poverty guidelines (FPG) as a benchmark, the income measure used to determine eligibility for federal programs, take a look at how EITC receipts vary with the number of eligible children.

A single worker with two children and earnings at the FPG receives over $5,000 from the EITC, while a worker without children at the FPG receives only $225. It is important to note that the FPG varies by household size as a worker with two children has to earn more to support their family than a worker without children.

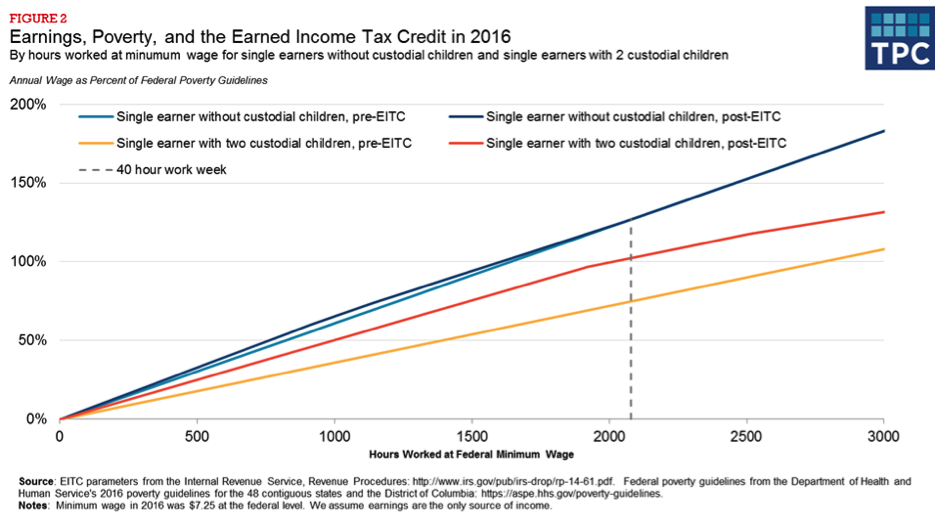

While the EITC does have a disparate impact for those at the FPG with and without children, the family size adjustments to FPG distort this picture. Consider a single full-time worker earning minimum wage. Without children, she would make around 125 percent of the FPG and receive no EITC. However, if she has two children, she earns less than 80 percent of the FPG before the EITC and barely crosses the guideline with the EITC.

The EITC plays an important role in lifting workers with custodial children out of poverty. That role does not extend to workers without custodial children – who receive little or no EITC at near-poverty level earnings. Our interpretation of the EITC relies on our understanding of fairness. If we think the EITC should treat those with equal incomes relative to poverty the same, then the program clearly fails to provide enough for childless workers. However, if we think that raising children makes it much harder to get out of poverty, then the EITC’s focus on workers with children is an equitable choice.