C-corporations pay entity-level tax on their income, and their shareholders pay tax again when the income is distributed. But in practice, not all corporate income is taxed at the entity level, and many corporate shareholders are exempt from income tax.

Income earned by C-corporations (named after the relevant subchapter of the Internal Revenue Code) is subject to the corporate income tax at a 21 percent rate. This income may also be subject to a second layer of taxation at the individual shareholder level, whether on dividends or on capital gains from the sale of shares.

Suppose a corporation earns $1 million in profits this year and pays $210,000 in federal taxes. If the corporation distributes the remaining $790,000 to its shareholders as dividends, the distribution would be taxable to shareholders. Qualifying dividends are taxed at a top rate of 20 percent, plus a 3.8 percent tax on net investment income. As a result, if the shares were held by high-income individuals only $601,980 would be left, and the combined tax rate on the income would be 39.8 percent = 0.21 + (1-0.21) * 0.238.

To alleviate double taxation of corporate income, other countries have “integrated” their corporate and shareholder taxes. Some countries permit corporations to deduct the dividends they pay to shareholders. Other countries give shareholders full or partial credit for taxes paid at the corporate level, or they permit shareholders to exclude dividends from their taxable income.

Impact on Business Behavior

Businesses have devised several ways to reduce the burden of double-taxation:

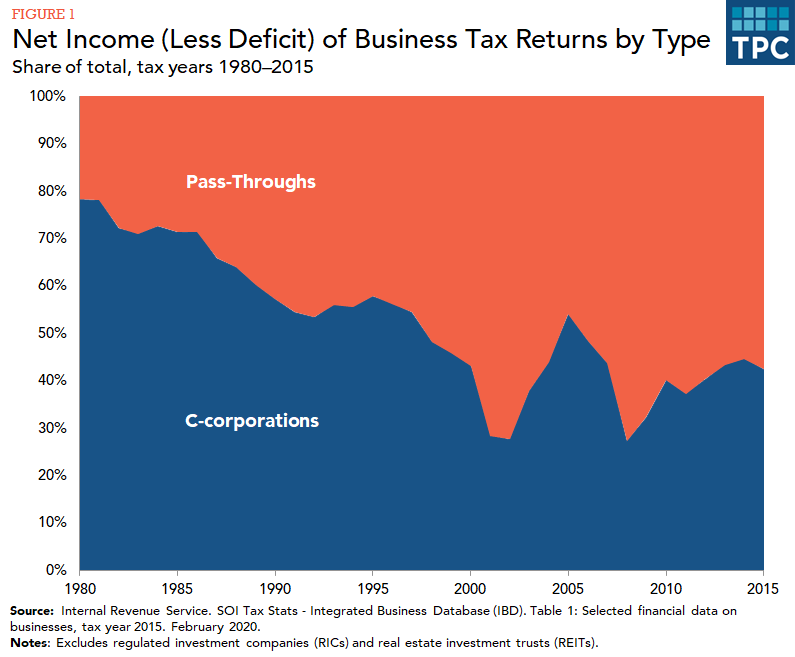

Choice of organizational form: Double taxation encourages businesses to organize as pass-through businesses (S-corporations, partnerships, limited liability companies, or sole proprietorships) instead of C-corporations. Pass-through profits are taxed only once at a top rate of 37 percent (or 29.6 percent if eligible for the Section 199A deduction). By no coincidence, the share of business activity represented by pass-through entities has been rising (figure 1). However, businesses that wish to list their shares for public trading generally need to organize as C-corporations.

Source of Financing (Debt versus Equity): Unlike dividends, which are paid out of after corporate tax income, interest is deductible. C-corporations can thus reduce the total tax paid on their income by issuing debt instead of stock to finance investment.

Payout Policy (Dividends versus Retained Earnings): C-corporations can also choose to retain their earnings rather than pay dividends. The corporation would still pay the corporate income tax on its earnings, but the shareholders would defer the second round of taxation until either the corporation distributed the earnings sometime in the future or the shareholders sold their stock at a price that reflected the value of the retained earnings. Deferral of taxation reduces the present value of its burden. The incentive to retain earnings created by shareholder-level taxation is known as “corporate lock-in.”

These tax-induced behavioral distortions have costs. Increased debt (leverage) elevates bankruptcy risk, especially during economic downturns. And corporate lock-in usually results in inefficient use of funds that could earn a higher real return if distributed to shareholders.

Most Shareholders are Not Subject to a Second Layer of Tax

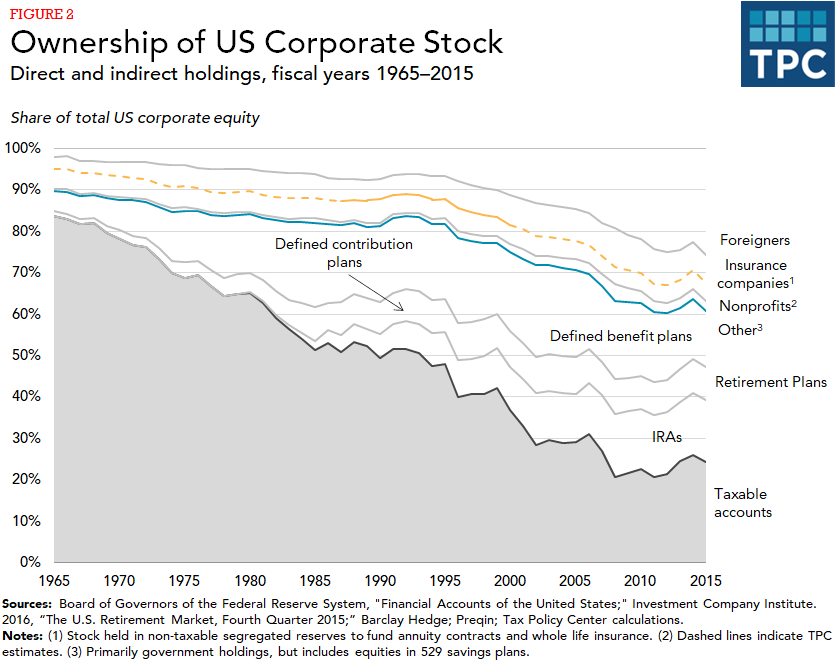

Often, however, there is not a second level of tax. Many shareholders of corporate stock, such as retirement accounts, educational institutions, and religious organizations, are exempt from income tax. US domestic law imposes a 30 percent withholding tax on dividends distributed to foreign shareholders, but many are exempted from this tax under bilateral tax treaties. The earnings distributed to these shareholders are therefore not double-taxed. By some recent estimates, the share of U.S. corporate stock held in taxable accounts has fallen from over 80 percent in 1965 to about 25 percent today (Rosenthal and Austin 2016).

Updated January 2024

US Department of the Treasury. 1992. Report of the Treasury on Integration of the Individual and Corporate Tax Systems. Washington, DC.

The White House and the US Department of the Treasury. 2012. “The President’s Framework for Business Tax Reform.” Washington, DC.