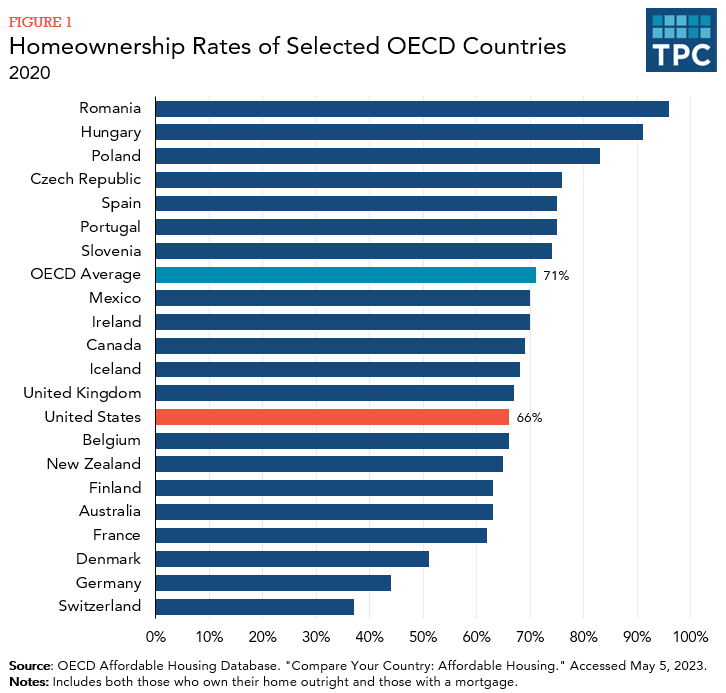

Probably not. The US homeownership rate is lower than in many other developed countries that do not offer similar tax subsidies for homeownership. Beyond a base level, US subsidies mainly support larger homes and second homes. Additionally, evidence suggests that the subsidies raise housing costs, thus dissipating their effectiveness in helping people buy their own homes.

According to the US Department of the Treasury, the federal government spent $243 billion in fiscal year 2022 in forgone tax revenue on housing and homeownership. This included the exclusion of imputed rental income, mortgage interest deduction, property tax deduction, exclusion of profits off home sales, and several other smaller tax provisions.

Contrary to popular belief, the mortgage interest deduction was not added to the tax code to encourage homeownership. The deduction existed at the birth of the income tax in 1913—a tax explicitly designed to hit only the richest individuals, a group for whom homeownership rates were not a social concern. The bulk of US homeownership tax subsidies go to middle- and upper-income households that likely own their homes anyway; thus, these subsidies simply facilitate their consumption of more housing. In addition, some evidence suggests that the tax subsidies raise housing costs, which could raise housing costs for those taking the standard deduction.

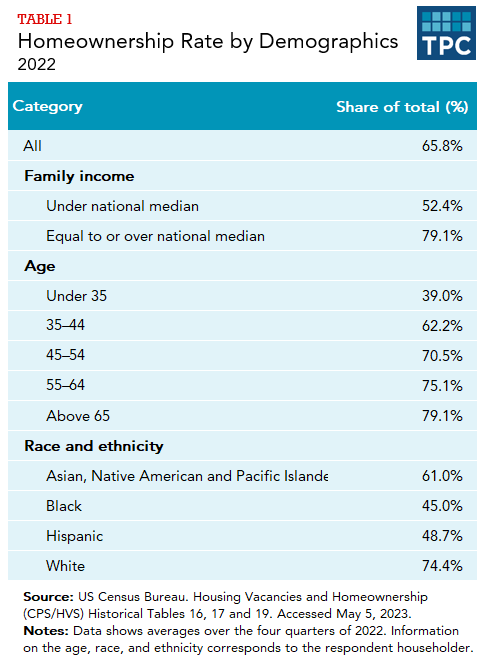

Sixty-six percent of all US households owned their homes in 2022. The homeownership rate was 70 percent or higher for those age 45 and over—and just under 80 percent for those over age 65. The homeownership rate for those under age 35 was only 39 percent. As expected, homeownership rates also increase with income, reaching nearly 80 percent for those with family income over the national median. Disparities are particularly large by race or ethnicity: under 50 percent of Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black households owned their homes in 2019, compared with 74 percent of non-Hispanic White households.

The US homeownership rate is lower than that of many other industrialized countries. Some provide similar tax benefits for ownership as the US while others do not. For example, Canada, with a homeownership rate marginally above that of the US, provides tax relief similar in scale to the US as a percentage of GDP; the United Kingdom, with a homeownership rate close to that of the US, provides much higher tax relief for homeowners as a percentage of GDP than does the US (OECD 2021). Both Canada and the UK exempt the proceeds from the sale of a primary residence from capital gains tax. Unlike the US, neither Canada nor the UK have a tax deduction for mortgage interest, but they both provide tax relief for first-time home buyers. For example, Canada provides a tax credit to first-time homebuyers and allows them to make tax-free withdrawals from retirement savings accounts to purchase their home. Many factors other than tax subsidies affect homeownership rates, including the ease of obtaining a mortgage, home prices, and cultural patterns, making cross-country comparisons difficult.

Some of the major tax benefits for homeowners are available only to taxpayers who itemize deductions, currently about 10 percent of all households. The deductions for home mortgage interest and for property taxes are thus worth more to high-income households because they are much more likely to itemize and because, facing higher tax rates, their tax saving is greater for each dollar deducted. These tax benefits help households that would likely own their own homes even without a tax subsidy. Low-income households, which typically are most in need of aid to afford homeownership, get little or no benefit from those deductions, because they more frequently use the standard deduction.

Beyond a base level, tax subsidies mainly support purchases of larger homes and second homes. In effect, the tax benefits encourage middle- and upper-income households to consume more housing than they otherwise would and to incur greater mortgage debt. Limits on the amount of mortgage debt for which taxpayers may deduct interest costs do, however, constrain those subsidies to the largest debts. to some degree.

Housing subsidies reduce the after-tax cost of housing at any given level of housing prices. This reduced cost raises demand for owner-occupied housing and thus drives up the price, particularly where land is scarce. By reducing the after-tax cost of housing, the subsidies enable people to pay more than they otherwise would. The resulting increase in demand for housing may cause prices to rise, and rise most in markets where supply cannot easily increase to meet that higher demand.

Updated January 2024

Andrews, Dana, and Aida Caldera Sánchez. 2011. “Drivers of Homeownership Rates in Selected OECD Countries.” OECD Economics Department Working Papers no. 849. Paris, France.

Carasso, Adam C., Eugene Steuerle, and Elizabeth Bell. 2005. “How to Better Encourage Homeownership.” Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Gale, William G., Jonathan Gruber, and Seth Stephens-Davidowitz. 2007. “Encouraging Homeownership through the Tax Code.” Tax Notes. June 18. Washington, DC.

Glaeser, Edward L., and Jesse M. Shapiro. 2003. “The Benefits of the Home Mortgage Interest Deduction.” Tax Policy and the Economy 17 (2003): 37–82.

Goodman, Laurie, and Christopher Mayer. 2018. “Homeownership and the American Dream.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Volume 32, Number 1, Winter 2018. pages 31–58.

Goodman, Laurie, Christopher Mayer, and Monica Clodius. March 2018. “The US Homeownership Rate Has Lost Ground Compared With Other Developed Countries.” Urban Wire (blog). Washington, DC: The Urban Institute.

Gruber, Jonathan, Amalie Jensen, and Henrik Kleven. 2017. “Do People Respond to the Mortgage Interest Deduction? Quasi-Experimental Evidence from Denmark.” NBER Working Paper No. 23600, Issued in July 2017. Cambridge, MA.

Harris, Benjamin H., and Lucie Parker. 2014. “The Mortgage Interest Deduction across Zip Codes.” Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Hilber, Christian A. L., and Tracy M. Turner. 2014. “The Mortgage Interest Deduction and Its Impact on Homeownership Decisions.” Review of Economics and Statistics 96 (4): 618–37.

Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. January 2020. “Racial Disparities and the Income Tax System.” Washington, DC.

Toder, Eric J. 2013. “Options to Reform the Home Mortgage Interest Deduction.” Testimony before the Committee on Ways and Means, US House of Representatives. Washington, DC.

Toder, Eric J. 2014. “Congress Should Phase Out the Mortgage Interest Deduction.” Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research 16 (1): 211–14.