At current tax rates, the direct revenue loss from cutting tax rates almost always exceeds the indirect gain from increased activity or reduced tax avoidance. Cutting tax rates can, however, partly pay for itself. How much depends on how people respond to tax changes.

Tax rates and revenues

Economic activity generally responds to tax changes. If you increase the tax on cigarettes, people will smoke less and some will shift to illegal, untaxed cigarettes. Income taxes also trigger a response. If you increase the tax rate on wages and salaries, some people will work less. (Some will also work more to recoup lost after-tax income, but evidence suggests that the disincentive effect dominates, with the effect particularly strong on the lower earner in a couple who is taxed jointly.) Similarly, if you increase tax rates on returns to saving and investing, such as interest, dividends, and capital gains, some people will save and invest less. (Here too some people may save more to maintain the same after-tax savings, but evidence suggests that the disincentive effect, though small, still dominates. However, that evidence is not as strong or consistent as in the case of the effects of tax rates on work, so more uncertainty surrounds the effect on saving.) In addition, lower corporate tax rates may lead to more investment in the US by foreign businesses, but here also the evidence for the magnitude of the effect is relatively weak.

Meanwhile, people will also respond by trying to avoid the tax increase without changing their underlying work or saving behavior. For example, some may work off the books or reclassify earnings to lower-tax forms of income. And some will devote more effort to using tax-advantaged retirement savings, charitable deductions, and other tax breaks to cut their taxable incomes. All these responses reduce the potential revenue gain from increasing tax rates.

The same is true in reverse. If the government reduces tax rates on an activity, people will do more of it and will devote less effort to legal avoidance and illegal evasion. In principle, those responses could be so large that a tax increase would reduce revenue or a tax cut would increase revenue. In practice, however, these paradoxical effects are extremely rare. Cutting tax rates thus almost never pays for itself in full.

But cuts can and do pay for themselves in part. If a 10 percent reduction in a tax rate yields a 3 percent increase in taxable income, for example, revenues fall by only 7 percent. Taxpayer responses would thus pay for 30 percent of the tax cut. Real-world examples can be more complex; a change in income tax rates, for example, could affect both payroll and income tax receipts.

The laffer curve

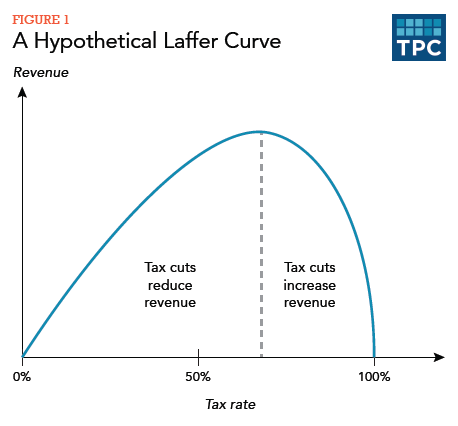

Economist Arthur Laffer helped popularize the idea that the revenue effects of tax changes depend on taxpayers’ response. Figure 1 shows a hypothetical Laffer curve that tracks how revenues depend on the tax rate.

We should expect that revenues would be very low when tax rates are close to either zero (when no revenue is raised regardless of the size of the tax base) or 100 percent (when there is an extreme disincentive to earn or report taxable income). At some point in between—65 percent in this hypothetical—revenues peak.

That much is uncontroversial. Debates often arise, however, about the shape of the Laffer curve and where on the curve current tax rates fall.

Responsiveness

A government’s ability to raise revenues by raising tax rates is limited by how people respond. For example, a local government’s ability to raise revenues by taxing hotel stays is limited by how easily potential hotel patrons can find accommodation in lower-tax communities. A state’s ability to tax personal incomes, by the same token, is limited by taxpayers’ willingness to move to lower-tax states to avoid the added levy. Likewise, the federal government’s ability to tax corporations is limited by corporations’ ability to move economic activity—in substance or merely in form—to lower-tax nations. And so on.

Responses depend on economic and policy conditions. A tax cut is a bigger deal, for example, when marginal tax rates are 70 percent than when they are 40 percent. Responsiveness also varies with the difficulty of changing behavior. Taxpayers can avoid capital gains taxes, for example, by holding appreciated stock and other assets until death or by donating them to charity. As a result, some analysts estimate that the Laffer curve for capital gains taxes peaks around a 30 percent federal rate. If the government scaled back those tax-reduction opportunities, however, taxpayers would have less ability to defer or avoid capital gains taxes and the peak rate would be higher.

Updated January 2024

Gale, William G., and Claire Haldeman. 2021. “The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act: A test of supply-side economics.” Washington DC: Brookings Institution.

Seliski, John, Aaron Betz, Yiqun Gloria Chen, U. Devrim Demirel, Junghoon Lee, and Jaeger Nelson. 2020. “Key Methods That CBO Used to Estimate the Effects of Pandemic-Related Legislation on Output.” Working Paper 2020-7. Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office.

Joint Committee on Taxation. 2018. “Overview of Joint Committee Economic Modeling.” Report JCX-33-18. Washington, DC: Joint Committee on Taxation.