For 2021, the child tax credit provided a credit of up to $3,600 per child under age 6 and $3,000 per child from ages 6 to 17. If the credit exceeded taxes owed, families could receive the excess amount as a refund. From July 2021 to December 2021, half of the credit was automatically paid on a monthly basis to most families in advance of their filing a tax return. Families could opt out of advance payments.

The American Rescue Plan increased the child tax credit (CTC) for 2021. Tax filers could claim a CTC of up to $3,600 per child under age 6 and up to $3,000 per child ages 6 to 17. There was no cap on the total credit amount that a filer with multiple children could claim. The credit was fully refundable, meaning low-income families qualified for the maximum credit regardless of how much they earned. If the credit exceeded taxes owed, families could receive the excess amount as a tax refund.

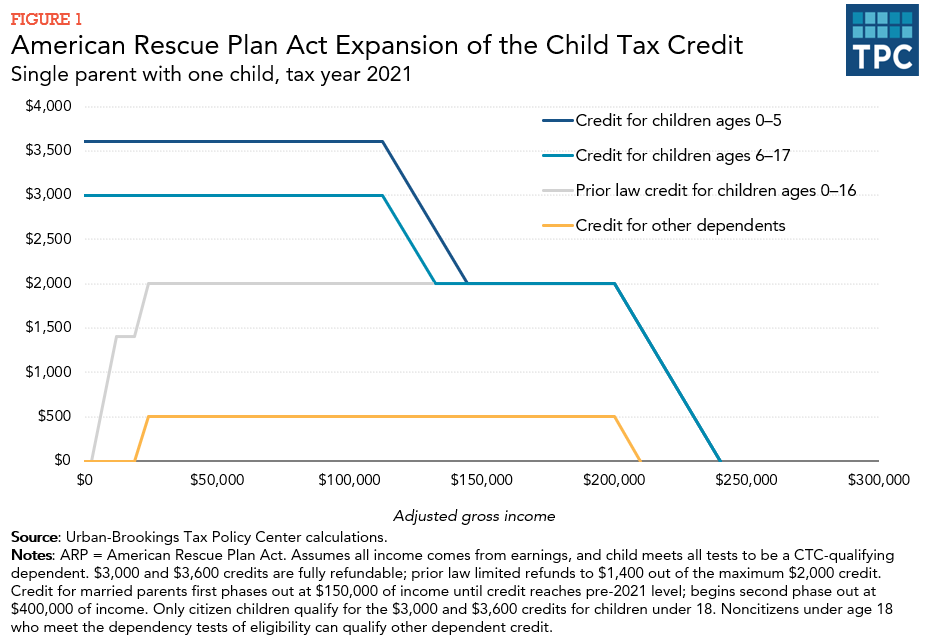

Prior law provided a CTC of up to $2,000 per child ages 16 and younger, with refunds limited to $1,400 per child. These parameters are back in effect again for tax years 2022 through 2025, although the amount of CTC that can be received as a refund is indexed to inflation and grew to $1,600 in 2023.

Other dependents—including children aged 18 and full-time college students ages 19–24—continued to receive a nonrefundable credit of up to $500 each in 2021.

Only children who were US citizens were eligible for these benefits. The maximum credit phased out in two steps. First, the maximum credit began to decrease at $112,500 of income for single parents ($150,000 for married couples), declining in value at a rate of 5 percent of adjusted gross income over that amount until it reached pre-2021 levels. Second, the credit was further reduced by 5 percent of adjusted gross income over $200,000 for single parents ($400,000 for married couples; figure 1, blue lines).

In 2021, most families received half of the CTC they were eligible for in monthly payments that were delivered from July to December, in advance of filing a tax return. A family with one child under 6 received a monthly payment of up to $300, and a family with one older child received up to $250 each month.

Families that received an advanced payment but were later determined ineligible based on updated income and household information when filing their taxes were not always required to repay the advanced credit. Low-income families whose eligibility changed because of a change in the number of children at home were only required to repay excess benefits above a “safe harbor” amount. Eligibility changes resulting from changes in income, in marital status, and in other household arrangements did not qualify for the safe harbor, and affected families were required to repay excess benefits in full.

Impact of the 2021 CTC Expansion

Child poverty decreased by nearly half to a record low of 5.2 percent in 2021 as a result of the CTC expansion. Making the CTC fully refundable and removing the 15 percent phase-in were key: maximum benefits under the expansion reached the 19 million children whose families’ earnings were too low to receive the full credit under prior income requirements. Prior to making the CTC fully refundable, a disproportionate share of Black and Hispanic children were left out of receiving the full CTC benefit. As a result of the CTC expansion, poverty rates for Black and Hispanic children dropped more than for other race and ethnic groups.

Throughout 2021, CTC monthly payment recipients reported lower rates of food insecurity, especially low-income recipients. Most recipients reported using the CTC to pay for essential and routine household expenses. In addition, some families improved their financial well-being by using the CTC to save and pay off debt. Black and Hispanic/Latine adults and low-income adults were more likely to use the credit to pay off debt. The financial buffer provided by the CTC allowed families to make longer-term changes: to spend time job searching, training for a career change, paying for childcare, or spending time caring for children.

CTC monthly payments also stabilized families’ incomes from month to month, potentially mitigating the negative effects of income volatility on children. Early research has identified positive effects of the 2021 CTC on health, including mental health and other behavioral outcomes.

Monthly Payments

The 2021 CTC was the largest tax credit program that the IRS has ever delivered through monthly advanced payments instead of as a lump sum at tax filing time. Parents generally preferred monthly payments, especially parents at lower income levels. Monthly and lump sum payments each help families address distinct sources of economic hardship.

CTC Effect on Employment

Since CTC payments increased families’ income, researchers and policymakers anticipated that it could cause some recipients to work less in response to the new benefit. Most, but not all, analysts have found that the CTC did not significantly reduce employment, or that employment rates did not significantly differ between recipients and nonrecipients. Estimates of long-term employment effects varied based on different assumptions about the strength of the labor market, how payments affect families at different income levels, and how families with one and two parents negotiate the balance between childcare and work. Receiving the credit may have even increased employment by enabling parents to pay for childcare. The effects of the CTC on parents’ employment could also be weighed against how receiving the credit in childhood can improve labor force participation later in life.

Participation in the 2021 CTC

CTC monthly payments reached 62 million children according to the IRS and the Government Accountability Office. Around 2 percent of these payments were made in error: either to people not eligible for the payments or to incorrect bank accounts. Since not all families are required to file taxes, the total population of eligible children is not known. Up to an estimated 5 million more eligible children missed out on monthly payments, though some of these families signed up for monthly payments after they began, and others claimed their benefits at tax time.

People who had not recently filed taxes or who had recently become parents are two examples of populations more likely to miss out on benefits. Families encountered informational, technological, and linguistic barriers to interacting with the tax system, and outreach efforts alone without efforts to reduce these barriers did not increase participation. Successful outreach efforts during the expansion employed trusted messengers and culturally specific messages to deliver tax information to eligible families. More work to simplify identity and employment verification can further reduce barriers to filing.

Updated January 2024

Browse Urban Institute's research on the CTC here.

Ananat, Elizabeth, Benjamin Glasner, Christal Hamilton, and Zachary Parolin. 2022. “Effects of the Expanded Child Tax Credit on Employment Outcomes: Evidence from Real-World Data from April to December 2021.” NBER Working Paper. Cambridge, MA: NBER.

Corinth, Kevin, Bruce Meyer, Matthew Stadnicki, and Derek Wu. 2021. “The Anti-Poverty, Targeting, and Labor Supply Effects of the Proposed Child Tax Credit Expansion.” BFI Working Paper. Chicago, IL: Becker Friedman Institute for Economics

Curran, Megan A. 2022. “Research Roundup of the Expanded Child Tax Credit: One Year On.” Poverty and Social Policy Report, 6 (9).

Enriquez, Brandon, Damon Jones, and Ernie Tedeschi. 2023. “The Short-Term Labor Supply Response to the Expanded Child Tax Credit.” Working Paper. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Godinez-Puig, Luisa, Aravind Boddupalli, and Livia Mucciolo. 2022. “Lessons Learned from Expanded Child Tax Credit Outreach to Immigrant Communities in Boston.” Washington, DC: Tax Policy Center.

Hamilton, Leah, Stephen Roll, Mathieu Despard, Elaine Maag, Yung Chun, Laura Brugger, Michal Grinstein-Weiss. 2022. “The Impacts of the 2021 Expanded Child Tax Credit on Family Employment, Nutrition, And Financial Well-Being: Findings from the Social Policy Institute’s Child Tax Credit Panel (Wave 2).” Brookings Global Working Paper #173. Washington, DC: Brookings Institute.

Karpman, Michael, and Elaine Maag. 2022. “Lack of Awareness and Confusion over Eligibility Prevented Some Families from Getting Child Tax Credit Payments.” Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Maag, Elaine, and Michael Karpman. 2022. “Many Adults with Lower Income Prefer Monthly Child Tax Credit Payments.” Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Pilkauskas, Natasha, Katherine Michelmore, and H. Luke Shaefer. 2022. “The Effects of Income on the Economic Well-Being of Families with Low Incomes: Evidence from the 2021 Expanded Child Tax Credit.” Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Poverty Solutions.

Walker, Fay, Mary Bogle, Elaine Maag. 2022. “Early Lessons on Increasing Participation in The Child Tax Credit.” Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Waxman, Elaine, Poonam Gupta, and Dulce Gonzalez. 2021. “Initial Parent Perspectives on the Child Tax Credit Advance Payments.” Washington, DC: Urban Institute.