The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act discouraged charitable giving by reducing the number of taxpayers claiming a deduction for charitable giving and by reducing the tax saving for each dollar donated.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) made major changes that discourage charitable giving relative to prior tax law. It lowered individual income tax rates, thus reducing the value of all tax deductions. It increased the standard deduction to $13,850 for singles and $27,700 for couples (in 2023), capped the state and local tax deduction at $10,000, and eliminated other itemized deductions—provisions that significantly reduced the number of itemizers and hence the number of taxpayers taking a deduction for charitable contributions. The new law also roughly doubled the estate tax exemption to $12.92 million for singles (in 2023) and double that amount for couples. That high level removes tax incentives for giving by some very wealthy households.

The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center estimates that the TCJA reduced the number of households claiming an itemized deduction for their charitable gifts from about 37 million to about 16 million in 2018 and reduced the federal income tax subsidy for charitable giving by one-third—for instance, from about $63 billion to roughly $42 billion in 2018.

Overall, the TCJA reduced the marginal tax benefit of giving to charity by more than 30 percent, raising the after-tax cost of donating by about 7 percent. Unless taxpayers increase their net sacrifice—that is, charitable gifts less tax subsidies—charities and those who benefit from their charitable works, not the taxpayers, bear the brunt of these changes.

Reducing Tax Rates

For taxpayers who itemize their deductions, the tax saving from charitable contributions depends on the donor’s marginal tax rate. For instance, a donor in the 32 percent tax bracket pays 32 cents less tax for every dollar donated; that is, an additional dollar of contribution costs the donor on net 68 cents. By lowering tax rates, though only modestly for individuals, the TCJA reduced the tax saving for each dollar donated.

Raising the Standard Deduction and Limiting Some Itemized Deductions

Taxpayers who choose to itemize their deductions on their income tax returns can deduct charitable contributions from income that would otherwise be taxed. This lowers the cost of charitable giving by the amount of taxes saved. Most taxpayers, however, do not itemize but instead claim the standard deduction because it is larger than the sum of their potential itemized deductions. Taxpayers who take the standard deduction cannot reduce their taxable income by the amount of their charitable contributions; only itemizers have an incentive to give to charities because it reduces their taxes.

The TCJA significantly increased the standard deduction amount. It also capped the deduction for state and local taxes at $10,000 and eliminated some other itemized deductions. The combined effect of these changes was to substantially reduce the number of taxpayers who itemize, and thus the number who take a deduction for charitable contributions.

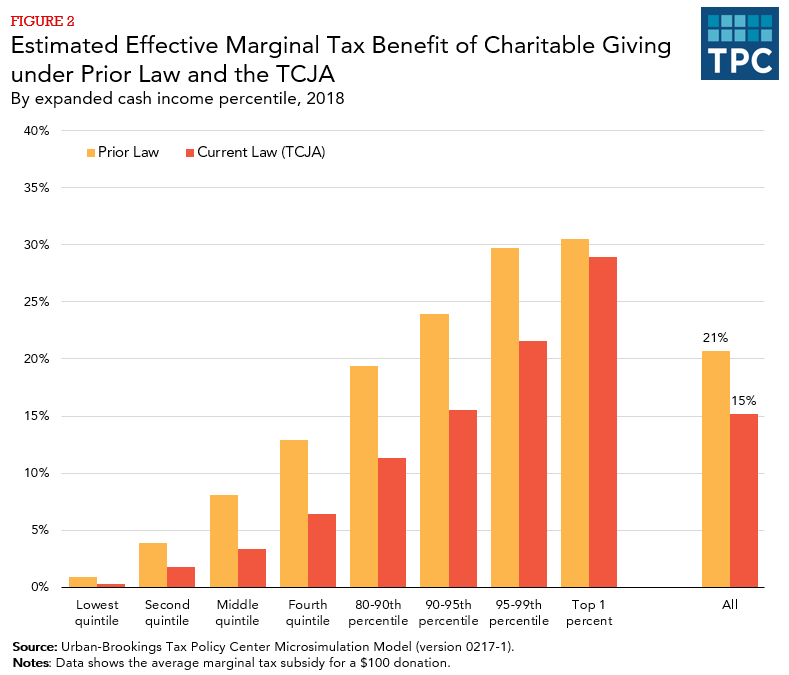

Before accounting for any changes in the amount of charitable giving, TPC estimates that the law cut the number of those itemizing their charitable contributions by more than half, from 21 percent to about 9 percent of households. The share of middle-income households, defined here as those in the middle quintile of the income distribution, claiming the charitable deduction fell by two-thirds, from about 17 percent to just 5.5 percent (figure 1).

The share of households itemizing their charitable contributions fell even among high-income households. The share of households in the 90th–95th percentile (those making between about $216,800 and $307,900), taking a deduction for charitable gifts dropped from about 78 to 40 percent, and the share itemizing among households in the 95th–99th percentile (those making between about $307,900 and $732,800) fell from 86 to 57 percent (figure 1).

While nonitemizers do not receive any subsidy for their current level of gifts, the incentive remains for a modest share of taxpayers to make large gifts. Thus, a couple filing a joint return and paying state and local taxes in excess of $10,000 and no other itemized deductions like mortgage interest, still has an incentive to give for giving in excess of $17,700 because, at that amount their total itemized deductions would exceed the standard deduction. Under prior law, which had a much lower standard deduction and no cap on deductible state and local taxes, the tax incentive for giving would have applied to a much larger share of their charitable donation.

Some taxpayers can avoid these limitations. An individual retirement account charitable rollover allows people aged 70 ½ to make direct transfers from their IRAs of up to $100,000 per year to qualified charities, without having to count these transfers as income for federal income tax purposes. Also, some taxpayers can bunch gifts. For instance, suppose a couple has $10,000 of state and local taxes and no other itemized deductions other possibly than charity. If they donate $15,000 of charitable contributions every year for five years, the standard deduction would be more valuable, so they would be unlikely to itemize their deductions. Instead, they could decide to give $75,000 away in one year only. That way would be able to deduct most of their charitable contributions, or $85,000 ($75,000 + $10,000 of state and local taxes) less the standard deduction ($27,700 in 2023). That way they would gain the advantages of both the increased standard deduction and a deduction for most of their charitable contributions.

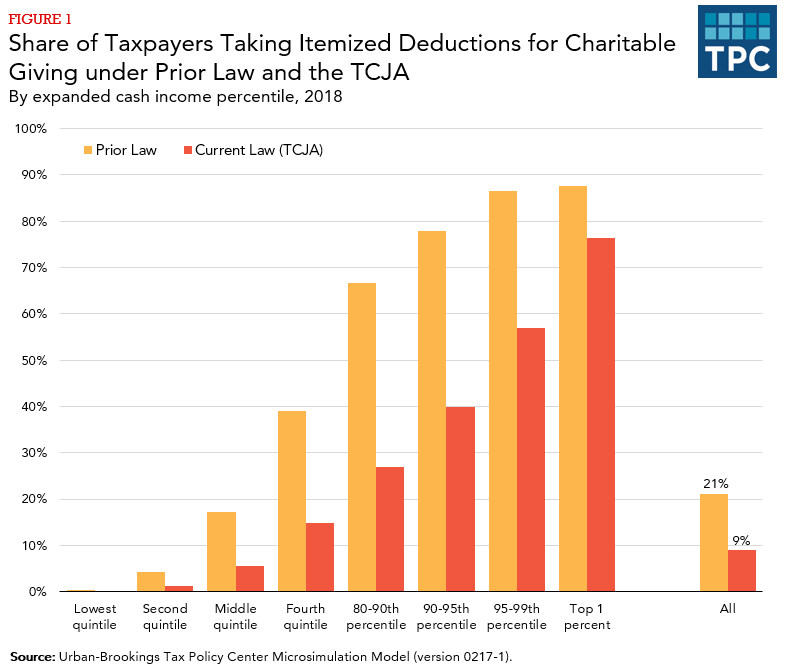

Average Subsidy for Charitable Giving

The combined effects of provisions in the TCJA that reduced both the number of itemizers and tax rates lowered the average subsidy for charitable giving (the marginal tax benefit averaged across all charitable gifts) from 20.7 percent to 15.2 percent. While the average subsidy for charitable giving declined significantly for low- and moderate-income taxpayers, it hardly changed for the highest-income taxpayers. For example, the average subsidy for middle-income taxpayers (those whose income places them between the 40th and 60th percentile of the income distribution) fell from 8.1 percent to 3.3 percent. By contrast, for those in the top 1 percent, it fell from 30.5 percent to 28.9 percent (figure 2).