The TCJA reduced some tax expenditure provisions, eliminated others, and introduced and expanded still others. In addition to these direct changes in tax expenditure provisions, an increase in the standard deduction and lower individual and corporate tax rates reduced the number of taxpayers using tax expenditure provisions and the value of the tax benefits they receive.

While the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) reduced overall federal receipts by about $1.5 trillion over 10 years, it did modestly reduce the net revenue cost of tax expenditures. Comparing the first post-TCJA Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) tax expenditure estimates to its last pre-TCJA estimates, the sum of the revenue losses for all tax expenditures for fiscal years 2018–20 (the years for which both JCT studies provide estimates) declined from $5.0 trillion to $4.5 trillion. (The total revenue losses from tax expenditures do not exactly equal the sum of losses from each provision because of interactions among the provisions, but studies by the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center have shown that the simple sum of revenue losses from separate provisions is a reasonably good approximation of the revenue loss of tax expenditures including these interactions.)

The TCJA eliminated and reduced some tax expenditures while introducing some new ones and increasing some existing ones. In addition, interactions between tax expenditures and changes in the law affected the number of taxpayers who benefit from tax expenditure provisions and the value of benefits they receive. The most important of these indirect effects comes from lower individual and corporate income tax rates, which reduce the value of many tax expenditures, and the increase in the standard deduction which reduces tax benefits from itemized deductions.

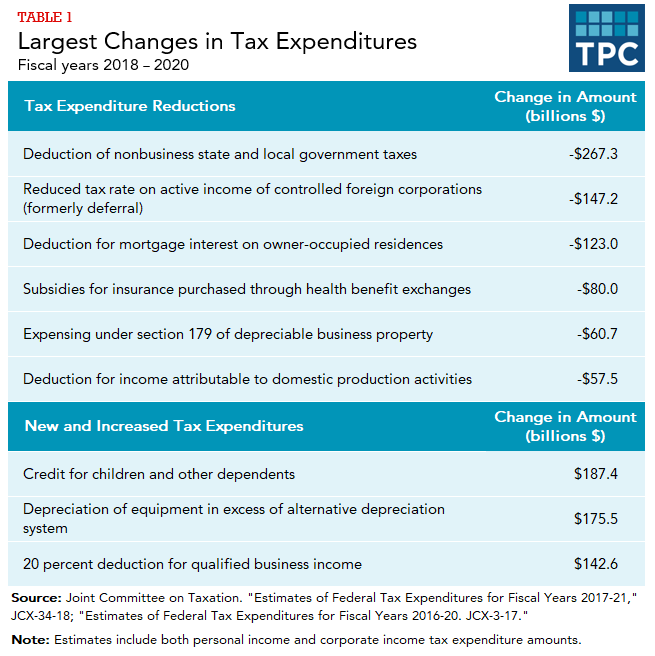

The tax expenditures that the TCJA reduced the most in fiscal years 2018–20 were the deduction of nonbusiness state and local income and property taxes, replacement of deferral by a reduced tax rate on the active income of controlled foreign corporations, deductions for mortgage interest on owner-occupied residences, subsidies for insurance purchased through health benefit exchanges, expensing of business depreciable property for small businesses under section 179, and the deduction for income attributable to domestic production activities (table 1).

The existing tax expenditures that the TCJA increased the most were the credit for children and other dependents and depreciation of equipment in excess of the alternative depreciation system. The largest new tax expenditure enacted in the TCJA was a 20 percent deduction for qualified business income (table 1).

Direct changes in tax expenditures

Most of the tax expenditures that the TCJA eliminated were small. The principal exception was the deduction attributable to domestic production activities ($58 billion in 2018–20), which was 9 percent of taxable business income. (For large corporations, the deduction was equivalent to a cut in the tax rate on profits from domestic production from 35 to 31.9 percent.) With the lower corporate tax rate from the TCJA, Congress believed this deduction was no longer needed to reduce the tax burden on domestic manufacturing.

The TCJA raised much more revenue from reducing several large tax expenditures instead of eliminating them. It reduced the value of the nonbusiness state and local income, sales, and property tax deductions in fiscal years 2018–20 to less than one-quarter its former cost. This resulted from a combination of changes: a $10,000 cap on the amount of taxes taxpayers could claim as a deduction; an increase in the standard deduction and reductions in other itemized deductions, which reduced the number of taxpayers claiming the deduction; and modestly lower individual income tax rates, which reduced the tax saving for taxpayers who claim it.

International provisions in the TCJA also reduced tax expenditures. The replacement of deferral of the profits of controlled foreign corporations until repatriation with a reduced tax rate on intangible profits accrued in low-tax countries reduced estimated tax expenditures in 2018–20 by $147 billion. JCT previously scored deferral as costing $365 billion over the three-year period, while the estimated revenue loss from the reduced tax rate on accrued profits (10.5 percent instead of 21 percent) was $218 billion. More than 100 percent of the reduction is this tax expenditure was, however, attributable to a reduction in the corporate rate from 35 to 21 percent instead of the reform of international provisions.

The largest expansions were for the child credit and depreciation of equipment by businesses. The child tax credit was doubled from $1,000 to $2,000 per child. TCJA introduced a new $500 credit for dependents and other children receiving the regular child tax credit, it increased the income levels at which the credit phases out, and it increased the amount of the credit that could be refunded. These changes raised the estimated 2018–20 revenue loss from the child credit by $187 billion.

The largest new tax expenditure, the 20 percent deduction for qualified business income received by owners of pass-through businesses (sole proprietorships, partnerships, limited liability companies, and subchapter S corporations), effectively reduces the top rate on qualified business income from 37 percent to 29.8 percent.

On the business side, the largest change was the enactment of 100 percent bonus depreciation for five years beginning in 2018 (and then phasing out at 20 percent per year beginning in 2023). Bonus depreciation raised the cost of depreciation of equipment in excess of the alternative depreciation system (JCT’s view of depreciation rules under the baseline income tax) by $176 billion between 2018 and 2020.

Indirect effects on the costs of tax expenditures

Lower marginal tax rates reduce the cost of tax expenditures that take the form of exclusions and deductions, because reducing taxable income provides smaller tax benefits at lower rates. TCJA modestly reduced the value of many individual tax expenditures by reducing the individual rate schedule from rates ranging from 10 to 39.6 percent to rates ranging from 10 to 37 percent.

The decline in the top corporate tax rate from 35 to 21 percent was much larger than the cut in the marginal individual rates. Most corporate tax expenditures are small, however, so the corporate rate cut per se did not change their total cost very much. Changes in what were the two of the three largest corporate tax expenditures before the TCJA (depreciation in excess of the alternative depreciation system and the domestic manufacturing deduction) were largely or wholly the result of other changes in the legislation (expensing of investment in equipment, and elimination of the domestic manufacturing deduction), while more than 100 percent of the reduction in tax expenditures for foreign-source income was a result of the lower corporate tax rate.

Other provisions of the legislation also had significant indirect effects on selected tax expenditures. The increase in the standard deduction significantly reduced the value of itemized deductions, which benefit taxpayers only to the extent that their sum exceeds the standard deduction. And the cap on the state and local deduction reduced the value of other itemized deductions, by also reducing the amount by which itemized deductions exceed the standard deduction.

For example, the cost of the mortgage interest deduction declined from $234 billion to $112 billion. Only a small portion of this decline came from the direct provisions affecting mortgage interest—the reduced ceiling on the size of new mortgages eligible for the deduction from $1 million to $750,000 and elimination of the deduction for up to an additional $100,000 of home equity loans. Most of the estimated saving was instead an indirect effect of the increase in the standard deduction, the $10,000 cap on state and local tax deductions, and lower marginal tax rates. The same indirect effects reduced the estimated cost of charitable deductions (other than for education and health) from $142 billion to $110 billion.

Indirect effects also reduced other tax expenditures. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that the elimination of the penalty tax on individuals without health insurance coverage would reduce the take-up rate for health insurance plans under the Affordable Care Act exchanges. The resulting reduction in coverage would then reduce tax subsidies paid out by the exchanges by about $80 billion between 2018 and 2020. On the business side, the estimated tax expenditure for small business expensing under section 179 declined from about $100 billion to about $40 billion between 2018 and 2020, even though the amount of deductions taken was made more generous. The estimated tax expenditure declined because, with bonus depreciation in place, the additional benefit of allowing expensing under section 179 is much less than it would have been without bonus depreciation.

Updated January 2024

Marron, Donald, and Eric Toder. 2013. “Tax Policy and the Size of Government.” Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Rogers, Allison, and Eric Toder. 2011. “Trends in Tax Expenditures: 1985–2016.” Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Toder, Eric, and Daniel Berger. 2019. “Distributional Effects of Individual Income Tax Expenditures After the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.” Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.