The corporate income tax is levied on business profits of C-corporations (named after the relevant subchapter of the IRS code). State and local governments collected a combined $99 billion in revenue from corporate income taxes in 2021.

Most US businesses, including sole proprietorships, partnerships, and certain eligible corporations, do not pay federal or state corporate income taxes. Instead, their owners must include an allocated share of the businesses’ profits (known as "pass-through" income) in their taxable income under the individual income tax. Over 95 percent of businesses were organized as pass-through entities in 2019. The remaining businesses, which have about half of all profits, pay the federal and state corporate income tax.

Forty-four states and the District of Columbia levy a corporate income tax. Ohio, Nevada, and Washington tax corporations' gross receipts instead of income. Texas levies a franchise tax on all businesses, including pass-through businesses, but excluding sole proprietorships. The Texas franchise tax is applied on business income or "margin" but the tax otherwise operates like a gross receipts tax (and the Census Bureau classifies its revenue as such). South Dakota and Wyoming do not tax business income.

How much revenue do state and local governments raise from corporate income taxes?

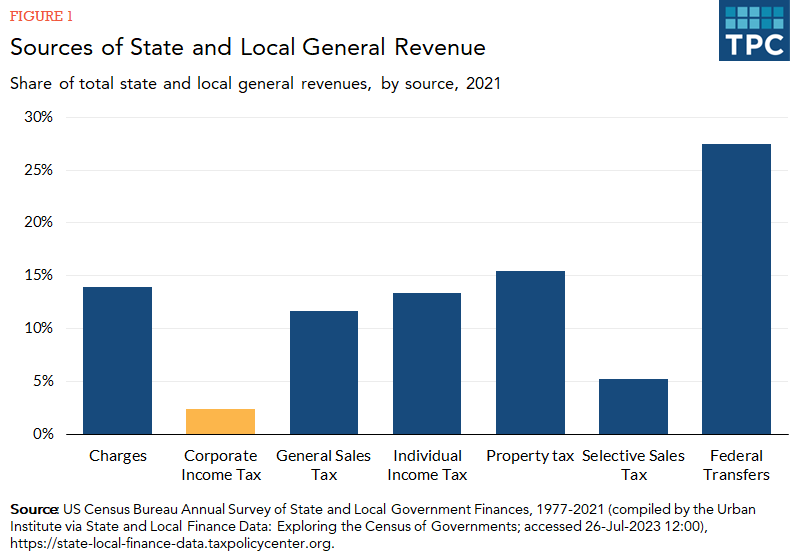

State and local governments collected a combined $99 billion in revenue from corporate income taxes in 2021, or 2 percent of general revenue. Corporate tax revenue collections in 2021 were notably higher than in 2020 when state and local governments collected $64 billion (in inflation-adjusted dollars). Some of the increase was the result of “tax shifting.” States delayed tax deadlines at the start of the pandemic, in the spring of 2020, and thus shifted some corporate tax collections from fiscal year 2020 (April) into fiscal year 2021 (July). That said, other factors, including strong economic growth, also drove robust corporate income tax collections in 2021.

Still, the share of state and local general revenue from corporate income taxes remained far smaller than the share from property taxes, general sales taxes, and individual income taxes in 2021. In fact, since 2001, state and local corporate income tax revenues have averaged 2 percent of general revenue.

State governments collected $89 billion in revenue from corporate income taxes in 2021, or 3 percent of state general revenue. Local governments collected $9 billion in revenue from corporate income taxes, or less than 1 percent of local general revenue. Local government corporate income tax revenue is low in part because only eight states allowed local governments to levy the tax in 2021. In fact, the local corporate income taxes in New York—that is, New York City’s corporate income tax—accounted for 77 percent of national local corporate income tax revenue in 2021.

Which states rely on corporate income tax revenue the most?

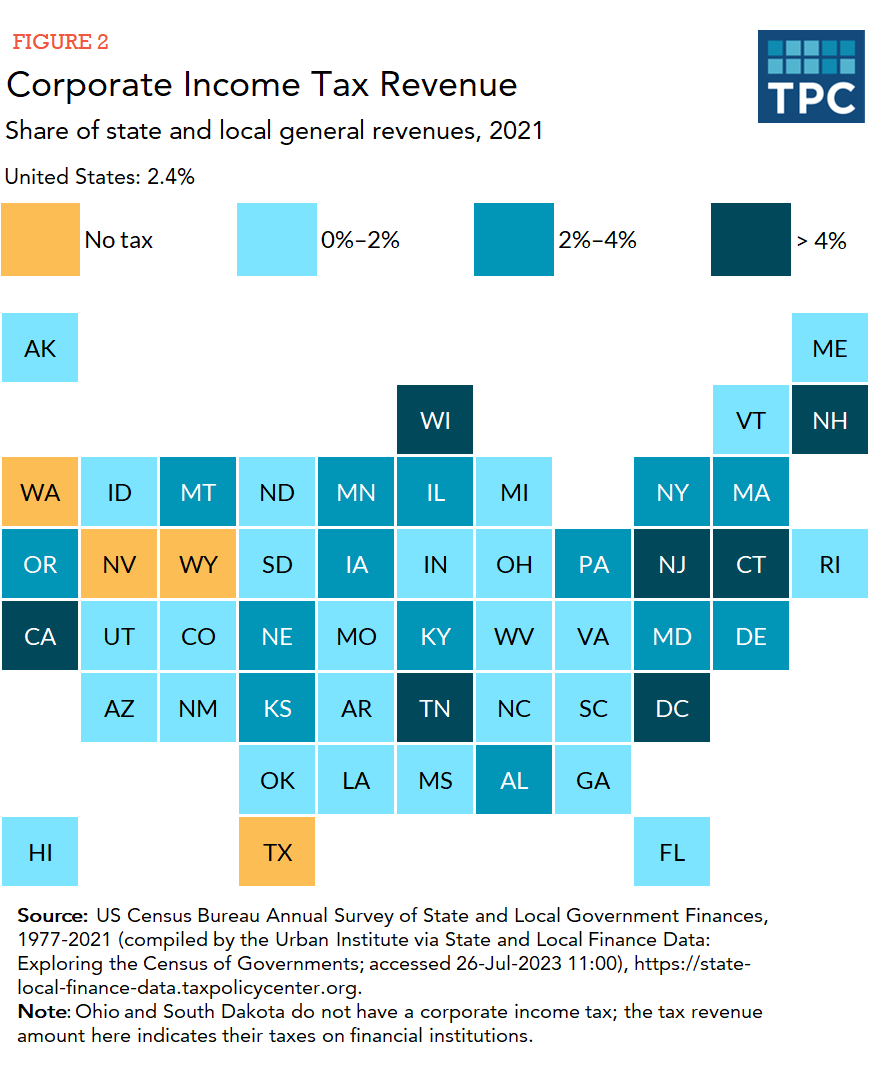

New Hampshire’s corporate income tax provided 7.3 percent of its state and local general revenue in 2021, the most of any state. (New Hampshire does not levy a broad-based individual income tax or general sales tax.) The corporate income tax accounted for more than 4 percent of state and local general revenue in five other states: Connecticut (4.9 percent), New Jersey (4.9 percent), Tennessee (4.1 percent), California (4.1 percent), and Wisconsin (4.0 percent). The District of Columbia collected 5.1 percent of its general revenue from the tax. In most states the corporate income tax accounted for less than 2 percent of general revenue. In New York, local corporate income taxes raised more revenue ($7.2 billion) than its state corporate income tax ($5.0 billion). In no other state did local corporate tax collections exceed $600 million in 2021.

Data: View and download each state's general revenue by source as a percentage of general revenue

The Census Bureau reports Ohio and South Dakota collected corporate income tax revenue in 2021 even though neither state had a broad-based corporate income tax because both levy special taxes on financial institutions. The resulting revenue is less than 1 percent of state and local general revenue in both states. Nevada, Texas, Washington, and Wyoming had no corporate income tax revenue in 2021.

How much do corporate income tax rates differ across states?

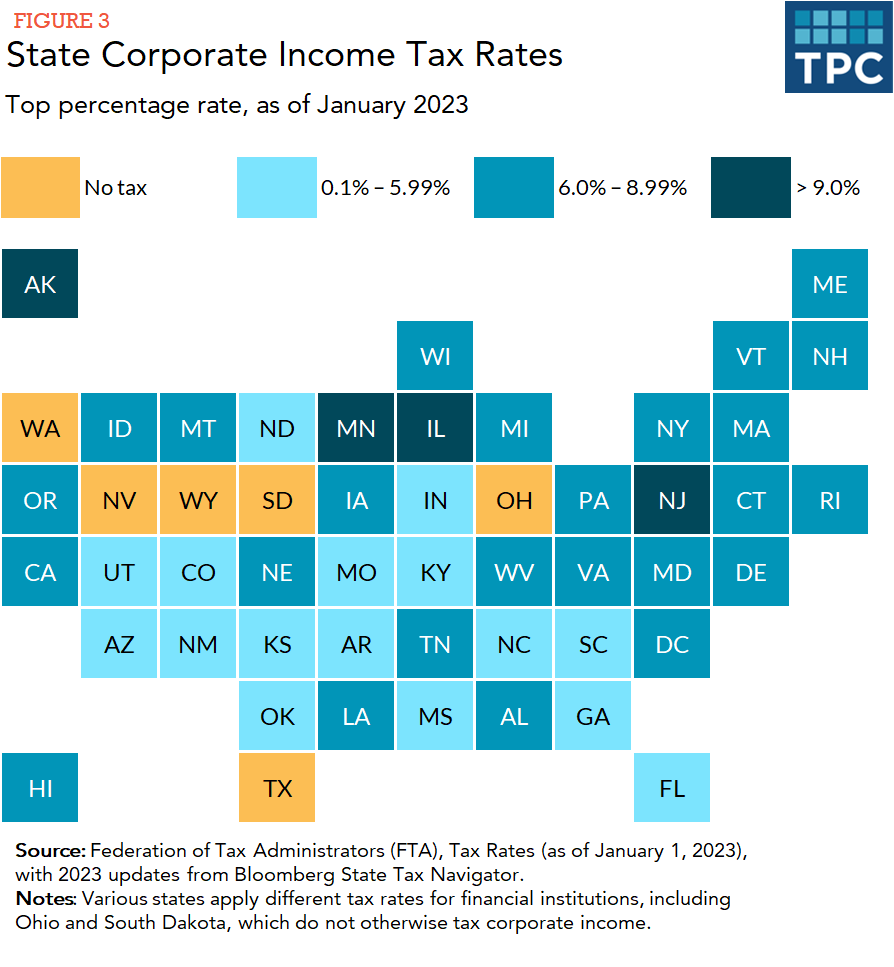

In 2023, top state corporate income tax rates range from 2.5 percent in North Carolina to 9.8 percent in Minnesota.

Data: View and download each state's top corporate income tax rate

Arizona, Colorado, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Utah all had top corporate tax rates lower than 5 percent. In contrast, Alaska, Illinois, Minnesota, and New Jersey had top tax rates of 9 percent or higher.

How do multistate corporations pay state corporate income taxes?

Most states use the federal definition of corporate income as the starting point for their state corporate income tax. States do deviate from the federal rules in some instances—for example, states use various rules for the treatment of net operating losses—but state corporate taxable income mostly mirrors federal taxable income. States use many federal corporate income tax definitions and rules in their tax code so they can benefit from the federal administration and enforcement of the corporate income tax.

However, states must take additional steps for multistate corporations to determine what portion of that income is taxable in each state.

States must first establish whether a company has "nexus" in the state—that is, enough physical or economic presence to owe corporate income tax. Next, the state must determine the taxable income generated by activities in their state. For example, multistate companies often have subsidiaries in no-tax or low-tax states that hold intangible assets, such as patents and trademarks. The rent or royalty payments to those wholly owned subsidiaries may or may not be considered income of the parent company operating in another state. Finally, states must determine how much of a corporation’s taxable income is properly attributed to that state.

For much of the twentieth century, most states used a three-factor formula based on the Uniform Division of Income for Tax Purposes Act to determine the portion of corporate income taxable in the state. That formula gave equal weight to the shares of a corporation’s payroll, property, and sales in the state. But over the past few decades states have moved toward formulas that rely more heavily or exclusively on a business's sales within the state to apportion income. As of January 2023, only four states used the traditional three-factor formula, while 29 states and the District of Columbia used only sales in their apportionment formula. The remaining states use property and payroll in their formulas but give greater weight to sales. By using the portion of a corporation’s sales rather than employment or property to determine tax liability, states hope to encourage companies to relocate or to expand their production operations within the states they operate in.

Updated January 2024

Dadayan, Lucy. 2023. State Tax and Economic Review. Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. (Reports are updated quarterly.)

Auxier, Richard C., and David Wiener. 2023. Who Benefited from 2022's Many State Tax Cuts and What is in Store for 2023?. Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. 2021. State Corporate Income Tax: Treatment of Net Operating Losses. Washington, DC.

Interactive Data Tools