The individual income tax (or personal income tax) is a tax levied on the wages, salaries, dividends, interest, and other income a person earns throughout the year, generally imposed by the state in which the income is earned. State and local governments collected a combined $545 billion in revenue from individual income taxes in 2021.

In 2023, 41 states and the District of Columbia levy a broad-based individual income tax. New Hampshire taxes only interest and dividends. New Hampshire’s tax is being phased out and will be fully repealed in tax year 2027. Alaska, Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, and Wyoming do not tax individual income of any kind. Tennessee previously taxed bond interest and stock dividends but the tax was repealed effective in tax year 2021.

How much revenue do state and local governments raise from individual income taxes?

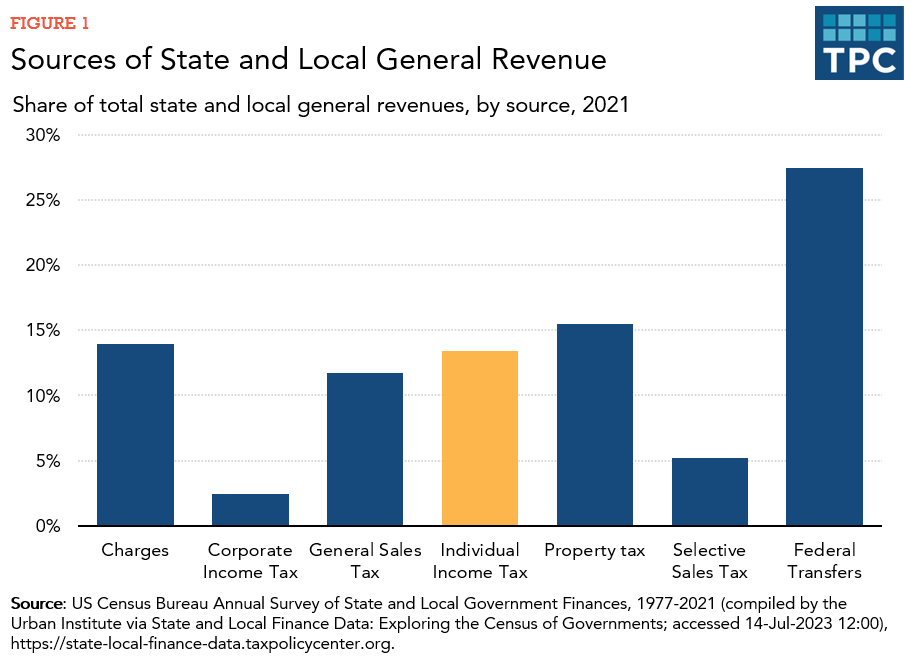

State and local governments collected a combined $545 billion in revenue from individual income taxes in 2021, or 13 percent of general revenue. That was a smaller share than state and local governments collected from property taxes and slightly more than what they collected from general sales taxes.

Individual income tax revenue collections in 2021 were notably higher than 2019 when state and local governments collected $445 billion (in inflation-adjusted dollars). Some of the increase was the result of “tax shifting.” States delayed tax deadlines at the start of the pandemic, in the spring of 2020, and thus shifted some individual income tax collections from fiscal year 2020 (April) into fiscal year 2021 (July). That said, other factors, including strong economic growth, also drove robust individual income tax collections in 2021.

In all years, individual income taxes are a major source of revenue for states, but they provide relatively little revenue for local governments. State governments collected $504 billion (19 percent of state general revenue) from individual income taxes in 2021, while local governments collected $42 billion (2 percent of local government general revenue).

In part, the share of local government revenue from individual income taxes is small because of state rules: only 11 states authorized local governments to impose their own individual income tax (or payroll tax) in 2021. In those 11 states, local individual income tax revenue as a percentage of local general revenue ranged from less than 1 percent in Alabama, Iowa, and Kansas to 19 percent in Maryland.

Localities in Indiana, Iowa, Maryland, and New York levy an individual income tax that piggybacks on the state income tax. That is, local taxpayers in these states file their local tax on their state tax return and use state deductions and exemptions when paying the local tax. The Portland, Oregon metro region also levies an income tax that piggybacks off of the state income tax, but only households earning more than $125,000 ($200,000 if filing jointly) pay the tax. Michigan localities also levy an individual income tax but use local forms and calculations.

Meanwhile, localities in Alabama, Delaware, Kentucky, Missouri, Ohio, Oregon, and Pennsylvania levy an earnings or payroll tax. These taxes are separate from the state income tax. Earnings and payroll taxes are typically calculated as a percentage of wages, withheld by the employer (though paid by the employee) and paid by individuals who work in the taxing locality, even if the person lives in another city or state without the tax. Additionally, some localities in Kansas tax interest and dividends but not wages.

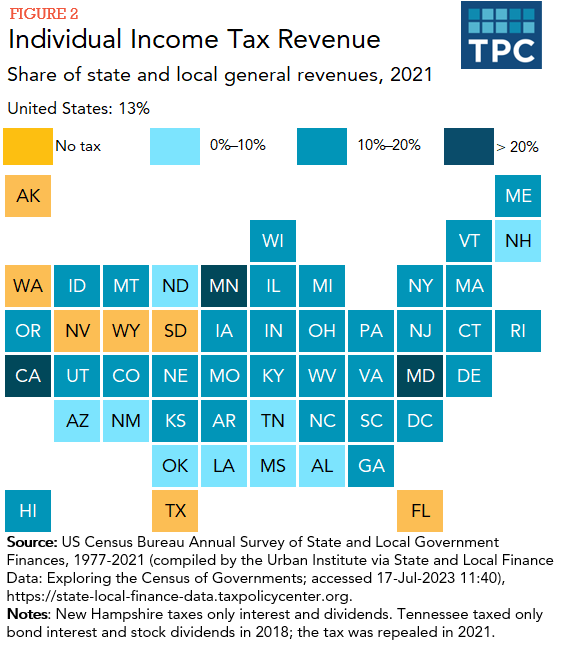

Which states rely on individual income taxes the most?

California collected 23 percent of its state and local general revenue from individual income taxes in 2021, the most of any state. The next highest shares that year were in Maryland (22 percent), Minnesota (20 percent), and New York (20 percent).

Data: View and download each state's general revenue by source as a percentage of general revenue

Among the 41 states with a broad-based individual income tax, North Dakota relied the least on the tax as a share of state and local general revenue (4 percent) in 2021. In total, eight of the 41 states with a broad-based tax collected less than 10 percent of state and local general revenue from individual income taxes that year. In 2021, New Hampshire taxed a very narrow base of income, and as a result income taxes provided about 1 percent of state and local general revenue in the state that year. Washington's capital gains tax took effect in tax year 2023 so there were no collections in 2021.

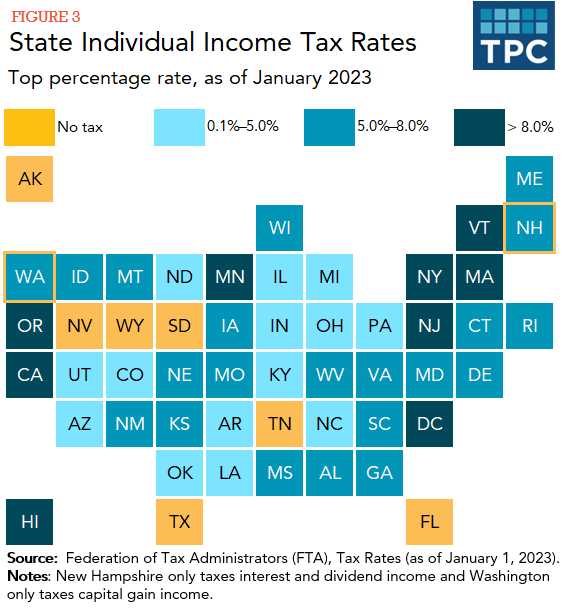

How much do individual income tax rates differ across states?

In 2023, the top state individual income tax rates range from 2.5 percent in Arizona to 13.3 percent in California. The next highest top individual income tax rates are in Hawaii (11 percent), New York (10.9 percent), and New Jersey (10.75 percent). In total, eight states and the District of Columbia have top individual income tax rates above 8 percent.

Data: View and download each state's top individual income tax rate

In contrast, 18 states with a broad-based individual income tax have a top individual income tax rate of 5 percent or lower. Arizona, Indiana, North Dakota, Ohio, and Pennsylvania have a top tax rate below 4 percent.

Currently, 10 states with a broad-based tax use a single (flat) tax rate on all income, and three additional states are moving to a flat tax rate over multiple years. Hawaii has the most tax brackets with 12.

Further, unlike the federal individual income tax, many states that use multiple brackets have top tax rates starting at relatively low levels of taxable income. For example, the threshold for the top tax rate in Alabama (5 percent) begins at only $3,001 of taxable income. Thus, many state individual income taxes—even those with multiple rates—are relatively flat. The threshold for the top income tax rate is below $40,000 in taxable income in 19 states, not counting the 10 states with a flat tax rate. (These taxable income amounts are for single filers. Some states have different brackets with higher totals for married couples. See this table of state income tax rates for more information.)

But some states have more progressive rate schedules. For example, California's top rate (13.3 percent) applies to taxable income over $1 million. The District of Columbia and New Jersey both levy a 10.75 percent tax rate on taxable income greater than $1 million. New York's top tax rate (10.9 percent) applies to taxable income greater than $25 million.

What income is taxed?

States generally follow the federal definition of taxable income. According to the Federation of Tax Administrators, 31 states and the District of Columbia use federal adjusted gross income (AGI) as the starting point for their state income tax. Federal AGI is a taxpayer’s gross income after "above-the-line" adjustments, such as deductions for individual retirement account contributions and student loan interest. Another five states use their own definitions of income as a starting point for their tax, but these state definitions rely heavily on federal tax rules and ultimately roughly mirror federal AGI. Colorado, Idaho, North Dakota, Oregon, and South Carolina go one step further and use federal taxable income as their starting point. Federal taxable income is AGI minus the federal calculations for the standard or itemized deductions (e.g., mortgage interest and charitable contributions) and any personal exemptions (which the federal government currently sets at $0). That said, some AGI states (e.g., New Mexico) choose to use the federal standard deduction and personal exemption in their state tax calculations, while one taxable income state, Oregon, chooses not to.

However, across all states, state income tax rules can diverge from federal laws. For example, unlike the federal government, states often tax municipal bond interest from securities issued outside that state. Many states also allow a full or partial exemption for pension income that is otherwise taxable on the federal return. And in most states with a broad-based income tax, filers who itemize their federal tax deductions and claim deductions for state and local taxes may not deduct state income taxes as part of their state income tax itemized deductions.

Because states often use federal rules in their own tax systems, the Tax Cuts and Job Acts (TCJA) forced many states to consider changes to their own systems. This was especially true for states that used the federal standard deduction and personal exemption on their state income tax calculation (before the TCJA nearly doubled the former and eliminated the latter).

A similar dynamic (but with smaller fiscal ramifications) occurred when Congress expanded the federal earned income tax credit and child tax credit in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Because of connections between the federal and state tax codes, states that conform with these policies also saw increases in their state-level EITCs.

How do states tax capital gains and losses?

Four states and the District of Columbia treat capital gains and losses the same as federal law treats them: they tax all realized capital gains, allow a deduction of up to $3,000 for net capital losses, and permit taxpayers to carry over unused capital losses to subsequent years.

Other states offer a range exclusion and deductions not in federal law. Arkansas excludes at least 50 percent of all capital gain income and up to 100 percent of capital gains over $10 million, Arizona exempts 25 percent of long-term capital gains, and New Mexico exempts 50 percent or up to $1,000 of federal taxable gains (whichever is greater). Pennsylvania and Alabama only allow losses to be deducted in the year that they are incurred, while New Jersey does not allow losses to be deducted from ordinary income (see our table on state treatment of capital gains for more detail)

Unlike the federal government, which provides a preferential rate for long-term capital gain income, most states tax all capital gain income at the same tax rate as ordinary income. However, some states provide lower tax rates for capital gain income.

How do states tax income earned in other jurisdictions?

State income taxes are generally imposed by the state in which the income is earned. However, if a taxpayer owes income tax to both their resident state and a non-resident state, the resident state typically provides a credit equal to the non-resident tax payment so the taxpayer is not double-taxed. But if the worker resides in a state without an income tax and works in a state with a tax (e.g., New Hampshire and Massachusetts), the worker pays income tax to the non-resident state without a tax credit from their home state.

To ease complexity and competition, some states have entered into reciprocity agreements with other states that allow outside income to be taxed in the state of residence. For example, Maryland’s reciprocity agreement with the District of Columbia allows Maryland to tax income earned in the District by a Maryland resident—and vice versa. Typically, these are states with major employers close to the border and large commuter flows in both directions.

Updated January 2024

Auxier, Richard C., and David Wiener. 2023. Who Benefited from 2022's Many State Tax Cuts and What is in Store for 2023?. Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Auxier, Richard C. 2022. How Post-Pandemic Tax Cuts Can Affect Racial Equity. Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Dadayan, Lucy. 2023. State Tax and Economic Review. Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. (Reports are updated quarterly.)

Boddupalli, Aravind, Frank Sammartino, and Eric Toder. 2020. State Income Tax Expenditures. Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Maag, Elaine, and David Weiner. 2021. How Increasing the Federal EITC and CTC Could Affect State Taxes. Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Auxier, Richard C., and Frank Sammartino. 2018. The Tax Debate Moves To The States: The Tax Cuts And Jobs Act Creates Many Questions For States That Link To Federal Income Tax Rules. Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Sammartino, Frank, and Norton Francis. 2016. Federal-State Income Tax Progressivity. Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Gale, William G., Kim S. Rueben, and Aaron Krupkin. 2015. The Relationship between Taxes and Growth at the State Level: New Evidence. Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Interactive Data Tools

State and Local Finance Data: Exploring the Census of Governments