States use federal tax laws in their own state tax codes to make rules and definitions simpler for both taxpayers and tax administrators. However, “conformity” means federal tax changes can also affect state tax laws.

States have conformed with the federal individual income tax code in various ways since the tax was introduced over a century ago. In fact, some states originally levied state income taxes simply as a percentage of a resident’s federal tax liability. (North Dakota, Rhode Island, and Vermont used this calculation as recently as 2001.)

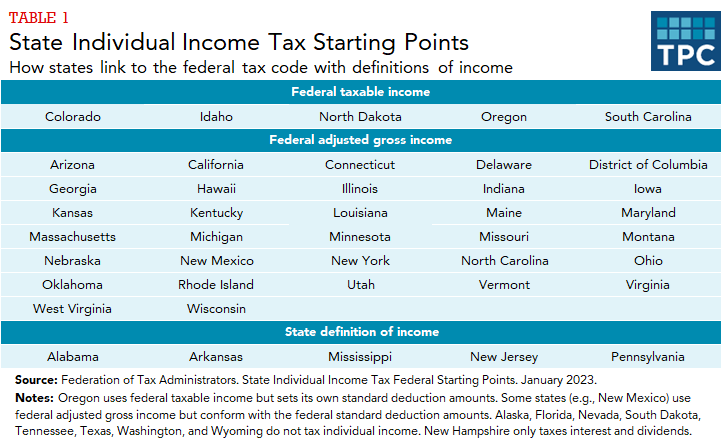

Today, most states conform through their definitions of income. Of the 41 states with a broad-based individual income tax, 31 states and the District of Columbia started their state income tax calculations with federal adjusted gross income (AGI) as of 2023. This is a taxpayer’s gross income after “above the line” federal adjustments, including eligible exemptions (e.g., employer contributions for health insurance) and deductions (e.g., student loan interest).

Another five states used federal taxable income as the starting point for their state income tax return. This is federal AGI minus the filer’s standard or itemized deductions (e.g., mortgage interest or charitable contributions).

Most of these states simply ask the filer to copy their AGI or federal taxable income from their federal tax form onto their state tax form. As a result, they accept all the federal definitions and rules that went into that calculation unless they explicitly “decouple” for a particular rule. This is why most state individual income tax expenditures (measured in revenue loss) are actually federal income tax expenditures the state has conformed with.

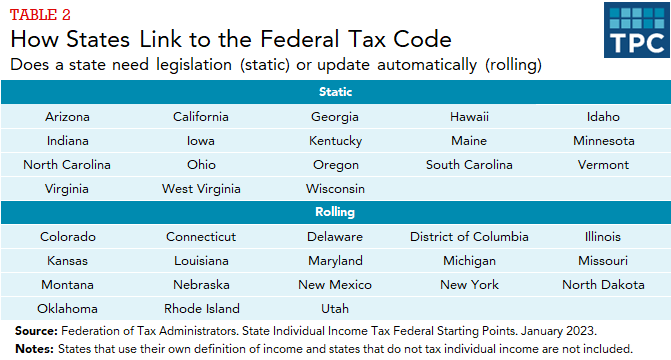

These 36 states and the District of Columbia connect to the federal tax rules on a “rolling” basis (i.e., they use the current federal tax code) or “static” basis (i.e., they use the federal tax code as of a fixed date, such as January 1, 2022). In a rolling state, federal tax law changes automatically affect the state’s tax code, while state legislators must pass legislation to accept federal changes in a static state. At the start of 2023, 18 states and the District of Columbia used a rolling basis, and 18 states used a static basis.

Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania do not use either federal AGI or taxable income as a starting point, but all five states refer often to Internal Revenue Service (IRS) rules and definitions to establish their state income tax base. For example, these states ask filers to list income amounts from their federal W-2 and 1099 forms on their state return.

In addition to definitions of income, some states use other parts of the federal tax law in their codes. For example, some states link to the federal child tax credit (CTC), child and dependent care tax credit (CDCTC), and earned income tax credit (EITC) in their own tax codes. States often provide these tax benefits as a percentage of the federal amount.

[Note: This page focusses on state individual income taxes but state corporate income taxes also conform with federal tax rules in a similar way.]

Why do states conform with federal rules?

When states link to the federal code, it benefits both their residents and their government’s tax administrators. Using federal rules and definitions simplifies state returns for taxpayers who only need one set of documents and calculations for both their federal and state returns. When states adopt the same federal laws, it also helps residents who earn income in multiple states. On the administrative side, states that use the federal code can rely on the IRS, Treasury Department, and federal courts for regulation, guidance, liability determinations, and compliance.

However, a state’s decision to conform with federal rules is always a choice, and a state can reject (or decouple) from any federal rule it does not want in its tax code. For example, most states start with the federal rules and definitions for itemized deductions, but do not let filers deduct state and local taxes on their state income tax return.

State tax conformity also means that when Congress changes federal laws, their actions can simultaneously affect state tax laws. If a state opposes those changes for its state tax system, it must then choose between keeping conformity and its built-in simplicity or decoupling and establishing new rules.

For example, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 eliminated the federal personal exemption, increased the federal standard deduction, and created a new deduction for pass-through business income. These federal changes affected states that used federal taxable income as their starting point at the time.

In response to the 2017 legislation, Minnesota and Vermont stopped using federal taxable income and began using federal AGI to ensure none of the TCJA changes affected their state individual income tax. Meanwhile, Colorado, Oregon, and South Carolina remained federal taxable income states but decoupled from the pass-through deduction. (Oregon and South Carolina completely removed the deduction from their state tax code while Colorado limited who could claim it.)

Similarly, the American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act of 2021 temporarily increased the federal EITC, and this affected states that used the federal rules in their state EITC calculations. No state decoupled from the ARP EITC changes, so all states using federal EITC rules also temporarily provided a larger state EITC in tax year 2021.

Updated January 2024

Maag, Elaine, and David Weiner. 2021. How Increasing the Federal EITC and CTC Could Affect State Taxes. Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Boddupalli, Aravind, Frank Sammartino, and Eric Toder. 2020. State Income Tax Expenditures. Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Maag, Elaine, and Richard Auxier. 2018. Addressing the Family-Sized Hole Federal Tax Reform Left for States. Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Auxier, Richard, and Frank Sammartino. 2018. The Tax Debate Moves to the States: The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Creates Many Questions for States That Link to Federal Income Tax Rules. Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.