All countries tax income earned by multinational corporations within their borders. The United States also imposes a minimum tax on the income US-based multinationals earn in low-tax foreign countries, with a credit for 80 percent of foreign income taxes they’ve paid. Most other countries exempt most foreign-source income of their multinationals.

Taxation of Foreign-Source Income

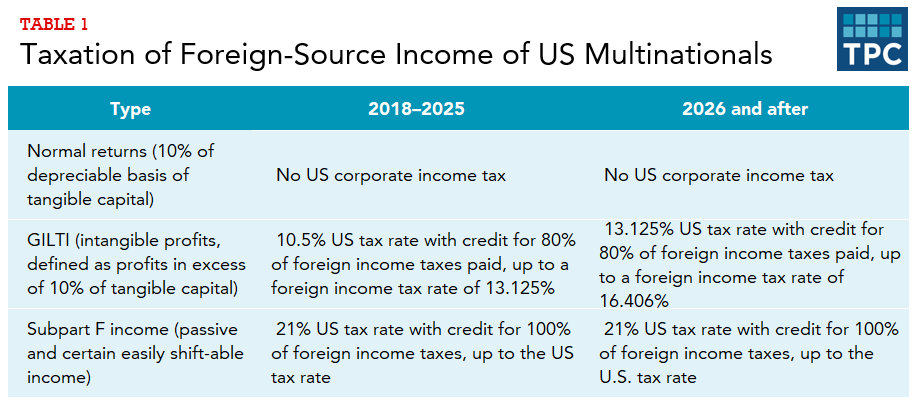

Following the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the federal government imposes different rules on the different types of income US resident multinational firms earn in foreign countries (table 1).

- Income that represents a “normal return” on physical assets—deemed to be 10 percent per year on the depreciated value of those assets—is exempt from US corporate income tax.

- Income above a 10 percent return—called Global Intangible Low Tax Income (or GILTI)—is taxed annually as earned at half the US corporate rate of 21 percent on domestic income, with a credit for 80 percent of foreign income taxes paid. Because half the US corporate rate is 10.5 percent, the 80 percent credit eliminates the GILTI tax for US corporations except for any income foreign countries tax at less than 13.125 percent. After 2025, the GILTI tax rate increases to 62.5 percent of the US corporate rate, or 13.125 percent, which makes US corporations subject to GILTI tax only on income foreign countries tax at less than 16.406 percent.

- Income from passive assets, such as bonds or certain categories of easily shiftable assets, is taxable under subpart F of the Internal Revenue Code at the full 21 percent corporate rate, with a credit for 100 percent of foreign income taxes on those categories of income.

US companies can claim credits for taxes paid to foreign governments on GILTI and subpart F income only up to their US tax liability on those sources of income. Firms may, however, pool their credits within separate income categories. Excess foreign credits on GILTI earned in high-tax countries, therefore, can be used to offset US taxes on GILTI from low-tax countries. US companies may not claim credits for foreign taxes on the 10 percent return exempt from US tax to offset US taxes on GILTI or subpart F income.

Suppose, for example, a US-based multinational firm invests $1,000 in buildings and machinery for its Irish subsidiary and earns a profit of $250 in Ireland, which has a 12.5 percent tax rate. It also holds $1,000 in an Irish bank, on which it earns interest of $50.

- The company pays the Irish government $31.25 of tax on the $250 of profits earned in Ireland plus another $6.25 on the $50 of interest from the Irish bank. Overall, it pays $37.50 of Irish tax on income of $300.

- The company owes no tax to the United States on the first $100 of Irish profits (10 percent of invested capital). It owes a tax before credits of $15.75 on the $150 of GILTI ($250 of profit less the $100 exempt amount). It owes $10.50 (21 percent of $50) on the interest from the Irish bank. So, overall its US tax before credits is $26.25.

- The company can claim a foreign tax credit of $21.25 from its Irish investments. This consists of $15 from the Irish tax on GILTI income (80 percent of .125 × $150) and the full $6.25 of Irish tax on interest income.

- So, overall, the US company pays $37.50 of tax to Ireland and an additional $5.00 to the United States ($26.25 less the $21.25 foreign tax credit) for a total tax liability of $42.50. This can be broken down into

- $12.50 of Irish tax on the first $100 of profits from the investment;

- $18.75 of Irish tax plus $0.75 of net US tax on the $150 of GILTI; and

- $6.25 of Irish tax plus $4.25 of US tax on the $50 of interest income.

TCJA also introduced a special tax rate for Foreign Derived Intangible Income (FDII)—the profit a firm receives from US-based intangible assets used to generate export income for US firms. An example is the income US pharmaceutical companies receive from foreign sales attributable to patents they hold in the United States. The maximum rate on FDII is 13.125 percent, rising to 16.406 percent after 2025. FDII aims to encourage US multinationals to report their intangible profits to the United States instead of to low-tax foreign countries.

Most countries, including all other countries in the G7 (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom), use a territorial system that exempts most so-called “active” foreign income from taxation. Still others have hybrid systems that, for example, exempt foreign income only if the foreign country’s tax system is similar to that in the home country. In general, an exemption system provides a stronger incentive than the current US tax system to earn income in low-tax countries because foreign-source income from low-tax countries incurs no minimum tax.

Many countries also have provisions, known as “patent boxes,” that allow special rates to the return on patents their resident multinationals hold in domestic affiliates.

Most other countries, however, also have rules similar to the US subpart F rules that limit their resident corporations’ ability to shift profits to low-income countries by taxing foreign “passive” income on an accrual basis. In that sense, even countries with a formal territorial system do not exempt all foreign-source income from domestic tax.

Inbound Investment

Countries, including the United States, generally tax the income foreign-based multinationals earn within their borders at the same rate as the income domestic-resident companies earn. Companies, however, have employed various techniques to shift reported profits from high-tax countries in which they invest to low-tax countries with very little real economic activity.

The US subpart F rules, and similar rules in other countries, limit many forms of profit shifting by domestic-resident companies but do not apply to foreign-resident companies. Countries use other rules to limit income shifting. For example, many countries have “thin-capitalization” rules, which limit companies’ ability to deduct interest payments to related parties in low-tax countries in order to reduce reported profits from domestic investments.

TCJA enacted a new minimum tax, the Base Erosion Alternative Tax (BEAT) to limit firms’ ability to strip profits from the United States. BEAT imposes a 10.5 percent alternative minimum tax on certain payments, including interest payments, to related parties that would otherwise be deductible as business costs.

Updated January 2024

Altshuler, Rosanne, Stephen Shay, and Eric Toder. 2015. “Lessons the United States Can Learn from Other Countries’ Territorial Systems for Taxing Income of Multinational Corporations.” Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Clausing, Kimberly A. 2020. "Profit Shifting Before and After the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act." January 20, 2020.

Dharmapala, Dhammika. 2018. “The Consequences of the TCJA’s International Provisions: Lessons from Existing Research.” Prepared for National Tax Association, 48th Annual Spring Symposium Program, Washington, DC, May 1.

Gravelle, Jane G. and Donald J. Marples. 2020. “Issues in International Corporate Taxation: The 2017 Revision (P.L. 115-97).” CRS Report R45186. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Updated February 20, 2020.

Joint Committee on Taxation. 2015. “Issues in Taxation of Cross-Border Income.” JCX-51-15. Washington, DC: Joint Committee on Taxation.

Kleinbard, Edward D. 2011. “The Lessons of Stateless Income.” Tax Law Review 65 (1): 99–172.

Morse, Susan C. 2021. “The Quasi-Global GILTI Tax.” Pittsburgh Tax Review 18.

Shaviro, Daniel N. 2018. “The New Non-Territorial U.S. International Tax System.” Tax Notes. July 2.

Toder, Eric. 2017. “Territorial Taxation: Choosing among Imperfect Options.” AEI Economic Perspectives. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute.