The EITC is the single most effective means tested federal antipoverty program for working-age households—providing additional income and boosting employment for low-income workers.

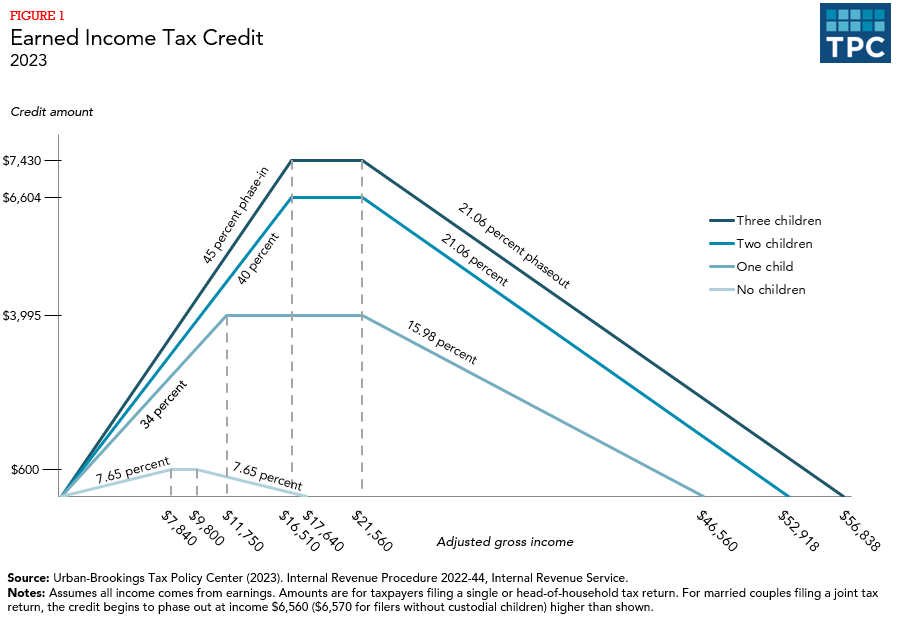

In 2023, the earned income tax credit (EITC) will provide maximum credits ranging from $538 for workers with no children to $6,660 for workers with at least three children (figure 1).

Poverty and the EITC

Official estimates of poverty compare the before-tax cash income of families of various sizes and compositions with a set of thresholds. The official poverty measure excludes the effect of federal tax and noncash transfer programs on resources available to the family. Thus, although the EITC adds income to poor households, it does not change the official number of those living in poverty.

To understand how the social safety net changes resources, the US Census Bureau has developed a supplemental poverty measure that includes additional resources available to families (and additional expenses) not captured in the official measure (Creamer 2022). To determine how well off a family is, the supplemental poverty measure compares resources available to resources needed, taking account of regional differences.

Resources needed include not only basic items such as food and housing, but also taxes and expenses such as those associated with work and health care. Resources available include government transfers, including noncash transfers, and refundable tax credits such as the EITC. Official Census publications show that together, the child tax credit and the EITC (both expanded in 2021) and the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (made refundable in 2021) lifted 9.6 million people out of poverty in 2021 (Creamer 2022). The Census Bureau estimates that around half of this effect (5.3 million people) came from the child tax credit, compared to 1.2 million people in 2020. While the CTC had an outsize effect in 2021, the EITC is typically the single most effective program targeted at reducing poverty for working-age households.

Reducing Poverty by Encouraging Work

Substantial research confirms that the EITC encourages single people and primary earners in married couples to work (Dickert, Houser, and Scholz 1995; Eissa and Liebman 1996; Meyer and Rosenbaum 2000, 2001) though more recent research has attributed increased labor participation to a historically strong labor market and other welfare reforms (Kleven 2020). The credit, however, appears to have little effect on the number of hours people work once they are employed. Although the EITC phaseout could cause people to reduce their work hours (because credits are lost for each additional dollar of earnings, effectively a surtax on earnings in the phaseout range), there is little evidence that this actually happens (Meyer 2002).

The most recent relevant study found that a $1,000 increase in the EITC led to a 7.3 percentage point increase in employment and a 9.4 percentage point reduction in the share of families with after tax and transfer income in poverty (Hoynes and Patel 2015). If this employment effect were included in census estimates of poverty reduction (rather than just the dollars transferred through the credit), the number of people lifted out of poverty would be much greater.

Updated January 2024

Bipartisan Policy Center. 2013. “Bipartisan Policy Center (BPC) Tax Reform Quick Summary.” Washington, DC: Bipartisan Policy Center.

Center for Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP). 2019. “Policy Basics: The Earned Income Tax Credit.” Washington DC: Center for Budget and Policy Priorities.

Creamer, John, Emily A. Shrider, Kalee Burns, and Frances Chen. 2022. “Poverty in the United States: 2021.” Washington, DC: Census Bureau.

DaSilva, Bryann. 2014. “New Poverty Figures Show Impact of Working-Family Tax Credits.” Off the Charts (blog). October 17.

Dickert, Stacy, Scott Houser, and John Karl Scholz. 1995. “The Earned Income Tax Credit and Transfer Programs: A Study of Labor Market and Program Participation.” Tax Policy and the Economy 9.

Eissa, Nada, and Jeffrey B. Liebman. 1996. “Labor Supply Response to the Earned Income Tax Credit.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 111 (2): 605–37.

Executive Office of the President and US Department of the Treasury. 2014. “The President’s Proposal to Expand the Earned Income Tax Credit.” Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President and US Department of the Treasury.

Hatcher Group. “Tax Credits for Working Families.”

Hoynes, Hilary, and Ankur J. Patel. 2015. “Effective Policy for Reducing Inequality? The Earned Income Tax Credit and the Distribution of Income.” NBER Working Paper 21340. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Internal Revenue Service. 2014. “Compliance Estimates for the Earned Income Tax Credit Claimed on 2006–2008 Returns.” Washington, DC: Internal Revenue Service.

Kleven, Henrik. 2020. “The EITC and the Extensive Margin: A Reappraisal.” NBER Working Paper No. 26405. Revised, first issued October 2019.

Maag, Elaine. 2015a. “Earned Income Tax Credit in the United States.” Journal of Social Security Law 22 (1).

Maag, Elaine. 2015b. “Investing in Work by Reforming the Earned Income Tax Credit.” Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Meyer, Bruce D. 2002. “Labor Supply at the Extensive and Intensive Margins: The EITC, Welfare, and Hours Worked.” American Economic Review 92 (2): 373–79.

Meyer, Bruce D., and Dan T. Rosenbaum. 2000. “Making Single Mothers Work: Recent Tax and Welfare Policy and Its Effects.” National Tax Journal (53): 1027–62.

Meyer, Bruce D., and Dan T. Rosenbaum. 2001. “Welfare, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and the Labor Supply of Single Mothers.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 116 (3): 1063–1114.

Pergamit, Mike, Elaine Maag, Devlin Hanson, Caroline Ratcliff, Sara Edelstein, and Sarah Minton. 2014. “Pilot Project to Assess Validation of EITC Eligibility with State Data.” Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

President’s Advisory Panel on Federal Tax Reform. 2005. Simple, Fair, and Pro-Growth: Proposals to Fix America’s Tax System. Washington, DC: President’s Advisory Panel on Federal Tax Reform.