Working parents are eligible for two tax benefits to offset child care costs: the child and dependent care tax credit and the exclusion for employer-provided child care. The credit benefits only a small share of parents because relatively few have formal child care expenses that qualify for the credit.

The Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit

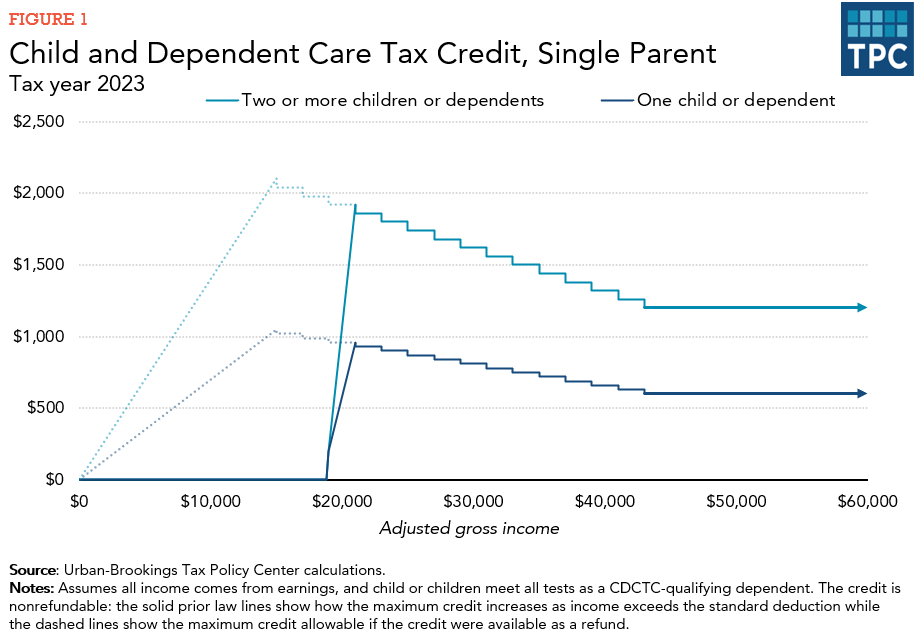

The child and dependent care tax credit (CDCTC) provides a credit worth between 20 and 35 percent of child care costs for a child under age 13 or any dependent physically or mentally incapable of self-care. Eligible child care expenses are limited to $3,000 per dependent (up to $6,000 for two or more dependents). Higher credit rates apply to families with lower adjusted gross income. Families with incomes below $15,000 qualify for the full 35 percent credit. That rate falls by 1 percentage point for each additional $2,000 of income (or part thereof) until it reaches 20 percent for families with incomes of $43,000 or more. The credit is nonrefundable so it can only be used to offset income taxes owed—in other words, any excess credit beyond taxes owed is forfeited. As a result, low-income families who owe little or no income tax get little benefit from the credit (figure 1).

Since expenses claimed for the credit cannot exceed earned income, a single parent must work to claim the credit. For married couples, generally both spouses must work since allowable expenses are capped at the earnings of the lower-earning spouse. For married couples, there is an exception to this rule if one spouse cannot work because they are disabled or a student. In these cases, the spouse's earned income is assumed to be $250 per month ($500 if there is more than one qualifying child).

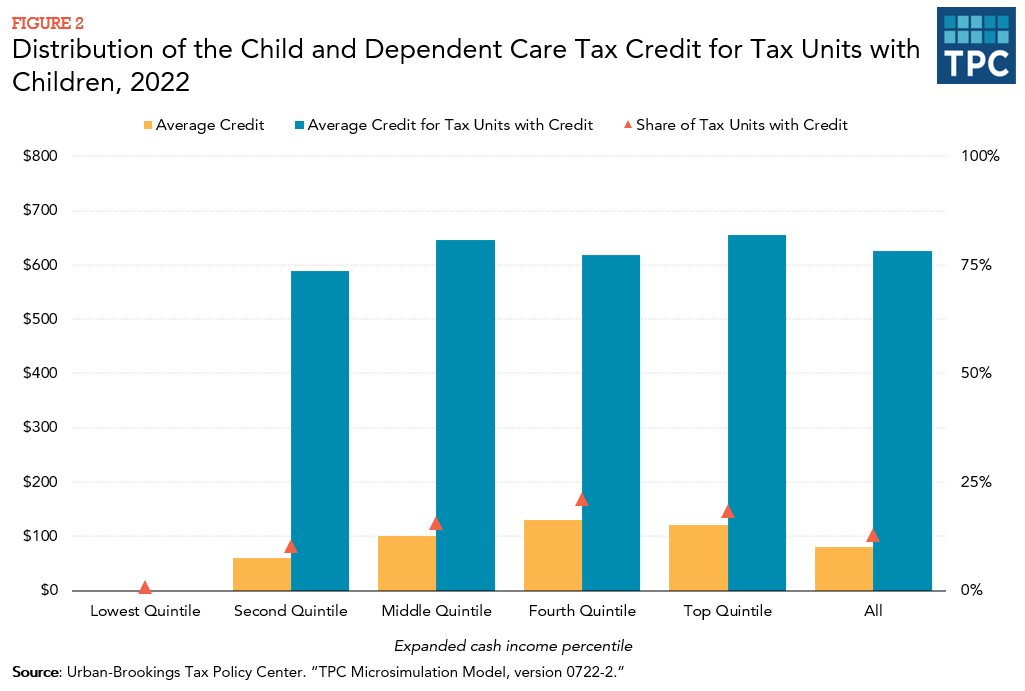

The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center estimates that, in 2022, 13 percent of families with children benefited from the CDCTC. Some families with children did not benefit because they did not have child care expenses or, in the case of married couples, only one partner worked or went to school. Among families with children who benefited from the CDCTC, taxes were reduced by an average of $625. The only income quintile in which families’ average benefits substantially differed was the lowest. Not only were their child care expenses likely to be lower than those of families in higher-income quintiles, they are typically unable to benefit from the credit because the CDCTC is nonrefundable (figure 2).

Employer Exclusion: Flexible Spending Accounts

Employer-provided child and dependent care benefits include amounts paid directly for care, the value of care in a day care facility provided or sponsored by an employer, and, more commonly, contributions made to a dependent care flexible spending account (FSA).

Employees can set aside up to $5,000 per year of their salary (regardless of the number of children) in an FSA to pay child care expenses. (FSAs are also available for health care expenses.) The money set aside in an FSA is not subject to income or payroll taxes. Unlike the CDCTC, though, which requires both partners in a married couple to work to claim benefits, only one parent must work to claim a benefit from an FSA. In 2014, 39 percent of civilian workers had access to a dependent care FSA (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014). Lower earners are less likely to have access to an FSA than higher earners (Stoltzfus 2015).

Interaction of CDCTC and FSAs

If a family has child care expenses that exceed the amount set aside in a flexible spending account, the family may qualify for a CDCTC. Families first calculate their allowable CDCTC expenses ($3,000 per child under age 13, up to $6,000 per family). If this calculation exceeds the amount of salary set aside in an FSA, a parent may claim a CDCTC based on the difference. For example, a family with two or more children can qualify for up to $6,000 of expenses to apply toward a CDCTC. If that family excluded $5,000 from salaries to pay for child care expenses in an FSA, it may claim the difference between the two ($1,000) as child care expenses for a CDCTC.

Higher-income families generally benefit more from the exclusion than from the credit because the excluded income is free from both income and payroll taxes. Most higher-income families with child care expenses qualify for a credit of 20 percent of their eligible expenses. Because the combined tax saving from each dollar of child care expenses excluded from income exceeds $0.20, the exclusion is worth more than the credit. The exclusion, however, is only available to taxpayers whose employers offer FSAs.

Neither the CDCTC nor the FSA are indexed for inflation. Thus, each year, the real (inflation-adjusted) value of benefits from the two provisions erodes.

Recent Legislative Changes

In 2021, the American Rescue Plan Act, expanded the child and dependent care tax credit (CDCTC) to temporarily provide a refundable credit of up to 50 percent of child care costs for a child under age 13 or any dependent physically or mentally incapable of self-care. Eligible child care expenses were limited to $8,000 per dependent (up to $16,000 for two or more dependents). After 2021, the credit returned to being nonrefundable and the maximum credit rate returned to 35 percent. Eligible child care expenses were once again limited to $3,000 per dependent (up to $6,000 for two or more dependents).

For 2021, there was a two-part phase-out for the 50 percent credit rate. Families with adjusted gross income below $125,000 qualified for the full 50 percent credit. That CDCTC rate then fell by 1 percentage point for each additional $2,000 of adjusted gross income (or part thereof) until the rate reached 20 percent (at $183,000 of income). Under the second part, the credit rate was reduced from 20 percent to 0 percent by one percentage point for each additional $2,000 of adjusted gross income (or part thereof) above $400,000 of adjusted gross income. The credit was fully phased out at $438,000 of adjusted gross income. After 2021, only the first part of the phase-out applies, the credit rate is not reduced below 20 percent.

Updated August 2024

Buehler, Sara J. 1998. “Child Care Tax Credit, and the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997: Congress’ Missed Opportunity to Provide Parents Needed Relief from the Astronomical Costs of Child Care.” Hastings Women’s Law Journal 9 (2): 189–218.

Burman, Leonard E., Jeff Rohaly, and Elaine Maag. 2005. “Tax Credits to Help Low-Income Families Pay for Child Care.” Tax Policy Issues and Options Brief 14. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Dunbar, Amy E. 2005. “Child Care Credit.” In Encyclopedia of Taxation and Tax Policy, 2nd ed., edited by Joseph J. Cordes, Robert D. Ebel, and Jane G. Gravelle, 53–55. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

Internal Revenue Service. “Publication 503—Main Content.” Accessed November 23, 2015.

Maag, Elaine. 2005. “State Tax Credits for Child Care.” Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Maag, Elaine. 2014. “Child-Related Benefits in the Federal Income Tax.” Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Maag, Elaine, Stephanie Rennane, and C. Eugene Steuerle. 2011. “A Reference Manual for Child Tax Benefits.” Perspectives on Low-Income Working Families brief 27. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Stoltzfus, Eli R. 2015. “Access to Dependent Care Reimbursement Accounts and Workplace-Funded Childcare.” Beyond the Numbers: Pay & Benefits 4 (1).