Taxing capital gains at the same rates as ordinary income would simplify the tax system by removing major incentives for tax sheltering and other attempts to manipulate the system. This could be accomplished by several different methods.

The Tax Reform Act of 1986, signed by President Ronald Reagan, raised tax rates on capital gains and lowered rates on ordinary income but set the same 28 percent top rate for both. The goal: reducing tax planning devoted to converting ordinary income to capital gains. The policy worked—briefly. Successive congresses raised the top rate on ordinary income (now 40.8 percent on most income) and reduced the top rate on capital gains (now 23.8 percent). As the gap between the two rates grew, so did the incentives to manipulate the system. Now might be a good time to once again tax capital gains and ordinary income at the same rate, which could be higher than today’s rate on capital gains but lower than the current rate on ordinary income.

In the 1980s, taxpayers exploited the ordinary income/capital gain gap by making investments that generated ordinary deductions—such as interest, lease payments, and depreciation—to reduce their current income tax liability. These taxpayers got their money back (and presumably more) in the form of long-term capital gains. The Tax Reform Act targeted these arrangements by limiting passive loss, interest, and accelerated depreciation deductions. Most importantly, it also eliminated the ordinary income/capital gain gap, thus making many tax shelter schemes unprofitable.

With the return of the ordinary/capital income tax differential, schemes to convert ordinary income into capital gains have followed. The Senate investigated one such scheme, basket options, which used the tax alchemy of derivatives to convert short-term into long-term capital gains. Private equity and other investment managers are often compensated with “carried interest,” which allows them to claim long-term gains rather than ordinary income treatment of most of their compensation.

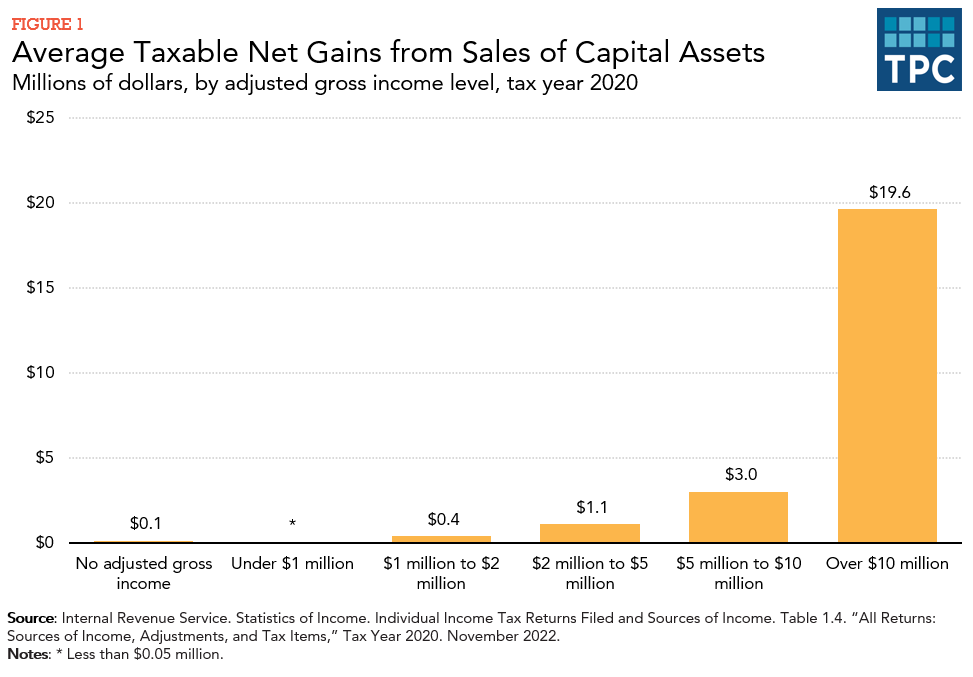

These planning opportunities are available only to the well-off, who hold the vast majority of capital assets and face the highest tax rates, thus deriving the most benefit from lower tax rates on capital gains (figure 1), although data in this figure are also affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Raising tax rates on capital gains could create a “lock-in” problem, as investors hold on to assets instead of selling them to avoid the tax. Annually taxing accrued capital gains, rather than realized gains, has been proposed as a method to eliminate lock-in. This method, sometimes called “mark-to-market”, is currently used to tax financial institutions and some financial products. By preventing “lock in”—holding property to defer tax liability (perhaps until death, when the heirs can completely avoid taxation of accrued gains on inherited assets) it could raise substantial revenue that would make it possible to reduce tax rates on both ordinary income and capital gains or reduce the deficit.

Mark-to-market would be difficult to apply to assets in closely held companies because it is difficult to determine their value. Alternatively, Congress could either tax capital gains at death or institute carryover basis so that heirs retain the lower basis of inherited assets. Either step would also reduce the tax incentive to keep assets until death and raise revenue.

Finally, if Congress is concerned about the potential double taxation of corporate earnings, it might integrate the two levels of taxes on corporate income. That is, Congress could tax corporate earnings only once, taxing the corporation or its shareholders but not both. The US Department of the Treasury (1992) has laid out several options for such integration.

Updated January 2024

Batchelder, Lilly L, and David Kamin. 2019. “Taxing the Rich: Issues and Options.”

Burman, Leonard E. 1999. The Labyrinth of Capital Gains Tax Policy: A Guide for the Perplexed. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Burman, Leonard E. 2012. “Tax Reform and the Tax Treatment of Capital Gains.” Testimony of Leonard E. Burman before the House Committee on Ways and Means and the Senate Committee on Finance, Washington, DC, September 20.

Rosenthal, Steven M. 2014. “Abuse of Structured Financial Products: Misusing Basket Options to Avoid Taxes and Leverage Limits.” Testimony before the US Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, Washington, DC, July 22.

Toder, Eric and Alan D. Viard. 2016. “Replacing Corporate Tax Revenues with a Mark-to-Market Tax on Shareholder Income.” National Tax Journal 69-3. September.

US Department of the Treasury. 1992. “Integration of the Individual and Corporate Tax Systems.” Washington, DC.