Think savings accounts with tax benefits—and a lot of rules.

Tax-deferred defined contribution plans include the familiar 401(k) plans, similar 403(b) plans for nonprofit employees, 457(b) plans for state and local government employees, and the federal government’s Thrift Savings Plan.

Participation

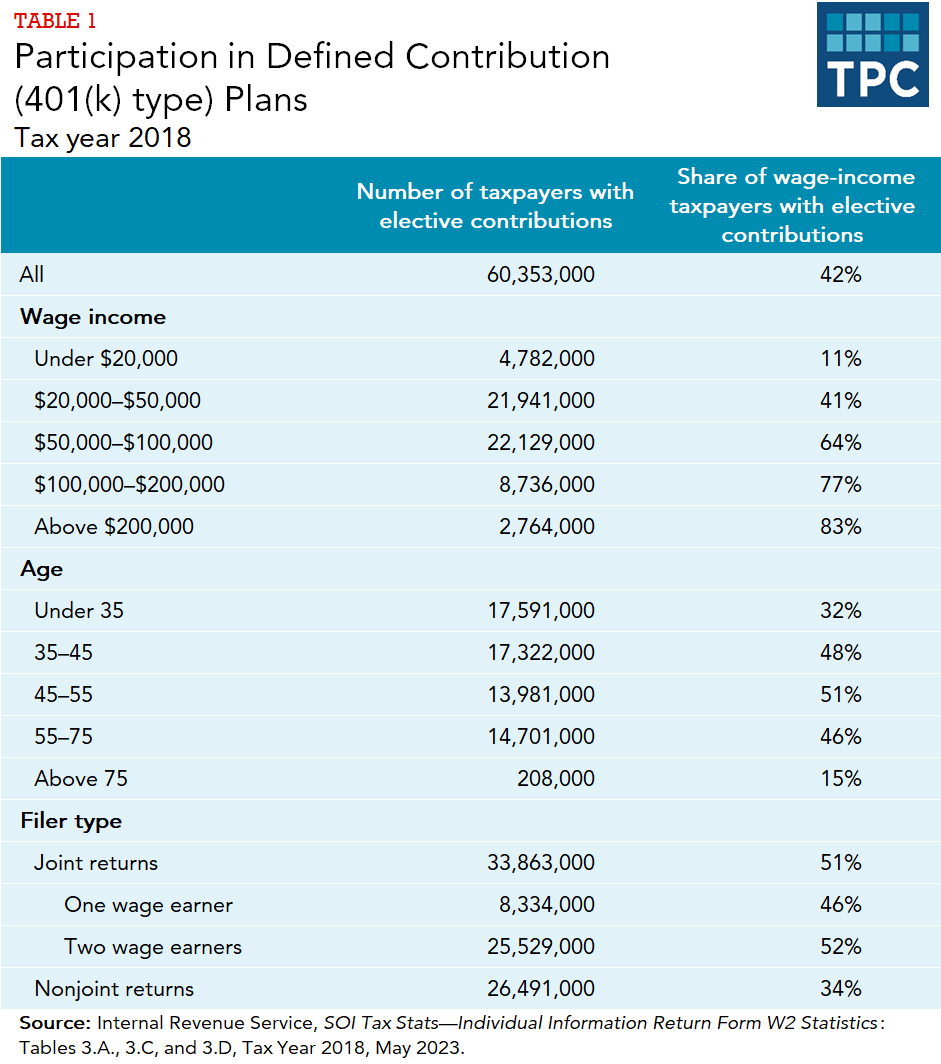

A little more than 40 percent of workers contributed to a defined-contribution plan in 2018. Workers’ participation in defined contribution plans generally increases with age and income. About three-quarters of workers earning $100,000 or more made contributions (table 1).

Contributions and Withdrawals

Contributions to defined contribution plans are tax deferred, meaning that neither the employer nor the employee pays tax on initial contributions or accumulating plan earnings. However, employees pay tax when they withdraw funds. The major exception is Roth-type defined-contribution plans. With Roth plans, account holders pay taxes when contributions are made rather than when contributions are withdrawn. With both types of plans, annual income accrued within the plans is tax-exempt.

Early withdrawals (before age 59½) from defined-contribution plans incur penalties (in addition to the regular tax on withdrawals), except in limited circumstances such as disability or very large medical expenses.

Balances

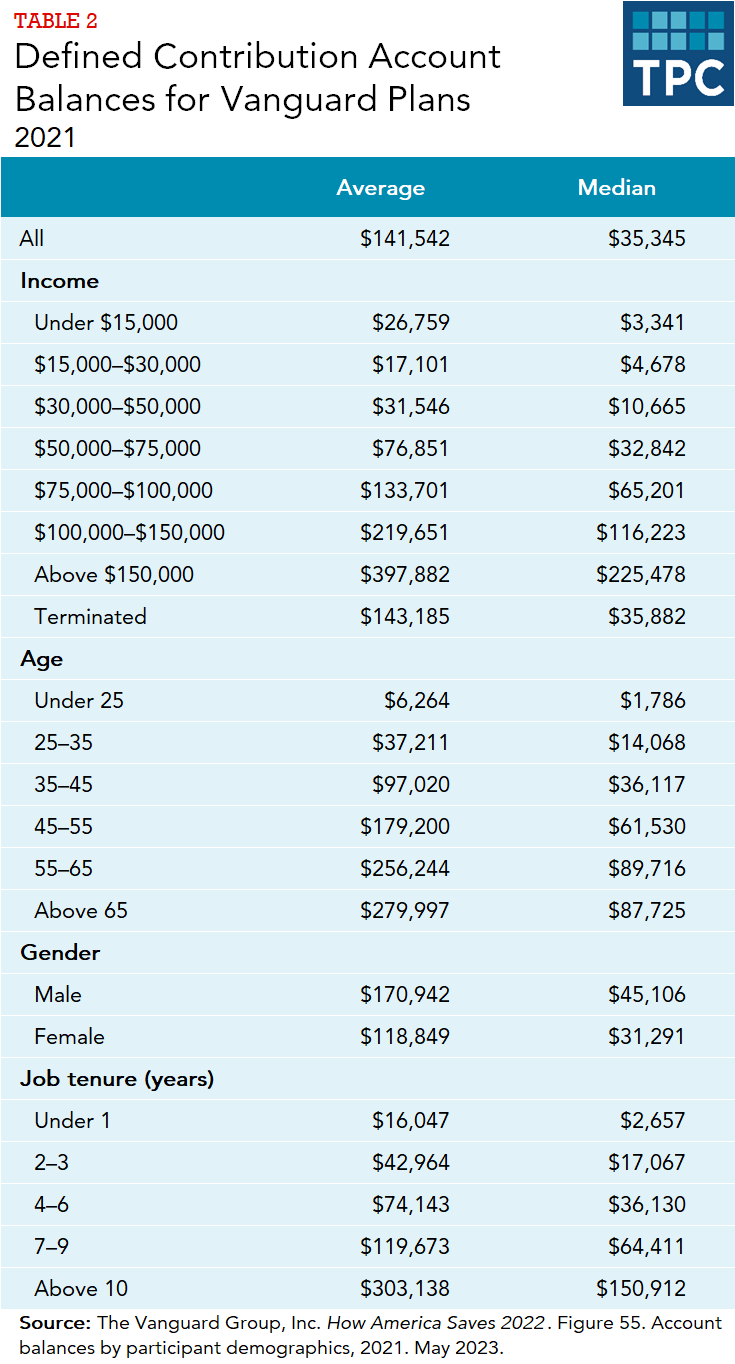

According to data from investment company Vanguard, the average defined contribution account balance was about $141,000 in 2021, while the median balance was just over $35,000. The median balance was higher by income, age (up to age 65), and job tenure. The median account balance for those age 55-65 was just under $90,000 in 2021. The median account balance was about $45,000 for men and just above $31,000 for women (table 2).

Risks

Defined benefit plans offer employees a contractually assured annuity at retirement. In contrast, under a defined contribution plan, an employee owns an account in which balances depend on the size of past contributions and on the investment returns those contributions accumulate. The employee bears the risk of underperforming assets and the possibility of outliving the income generated. But employees can manage this latter risk at retirement by using the assets in their plans to purchase annuities from insurance companies.

Updated January 2024

Burman, Leonard E., William G. Gale, Matthew Hall, and Peter R. Orszag. 2004. “Distributional Effects of Defined Contribution Plans and Individual Retirement Accounts.” Discussion Paper 16. Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Congressional Budget Office. 2007. “Utilization of Tax Incentives for Retirement Saving: Update to 2003.” Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office.

Employee Benefit Research Institute. 2015. “Chapter 5.” In EBRI Databook on Employee Benefits. Washington, DC: Employee Benefit Research Institute.

Kawachi, Janette, Karen E. Smith, and Eric J. Toder. 2006. “Making Maximum Use of Tax-Deferred Retirement Accounts.” Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Orszag, Peter R. 2004. “Balances in Defined Contribution Plans and IRAs.” Tax Notes 102 (5): 655.

Purcell, Patrick. 2007. “Pension Sponsorship and Participation: Summary of Recent Trends.” Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.