Social Security trust funds provide cash benefits for the elderly and disabled as well as for their spouses and dependents. They are funded chiefly through payroll taxes.

There are two Social Security trust funds: old-age and survivors insurance (OASI) and disability insurance (DI), though the two are often analyzed together as Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI). The funds finance benefits for eligible retired and disabled workers and their spouses, dependents, and survivors. When revenue dedicated to financing OASI and DI exceeds program expenses, the surplus is credited to the respective trust funds, which invest in special interest-bearing Treasury bonds. When program costs exceed receipts, the Social Security Administration can redeem its bonds to cover expenses, until it runs out of bonds. The US Department of the Treasury pays its interest obligation to the trust funds from general government funds.

Payroll Taxes: FICA and SECA

The Social Security trust funds are financed chiefly through payroll taxes on workers covered by the OASDI program. Employers and employees each contribute 5.3 percent of the employee’s taxable wages for OASI and 0.9 percent for DI coverage as part of what are sometimes called Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) taxes. For 2023, up to $160,200 in wages are subject to FICA taxes, a threshold updated for average wage growth each year. (Revenue from a separate 1.45 percent FICA tax is dedicated to the Medicare hospital insurance trust fund, and together they are often labeled by the public as the “Social Security” tax. There is no wage cap for the Medicare tax.) Because the employer portion of the tax raises the cost of hiring workers, economists believe that this tax is passed on to workers in the form of lower compensation. Thus, workers effectively bear the entire tax.

Self-employed workers covered by Social Security contribute both the employer and employee portions of the tax under the Self-Employment Contributions Act (SECA) but can deduct the employer portion from their federal taxable income, just as other employees exclude employer FICA contributions from their taxable income.

Other Financing Sources

Social Security benefits are partially taxable for beneficiaries whose incomes exceed a threshold. The revenues are remitted to the OASI, DI, and HI trust funds. The trust fund balances also earn interest from special interest-bearing Treasury bonds. Congress sometimes adds to the trust funds directly from general funds. For example, when the payroll tax was cut temporarily as a stimulus measure in 2011 and 2012, the general funds reimbursed the trust funds for lost revenue.

Trust Fund Solvency and Government-Wide Deficits

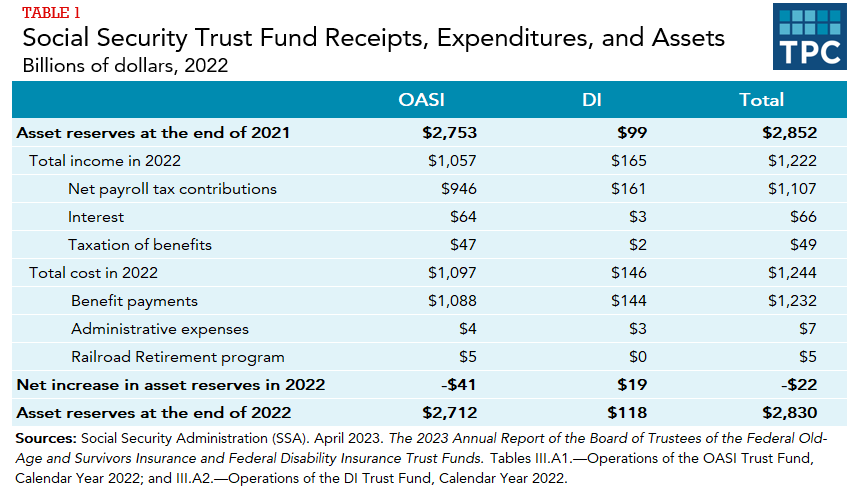

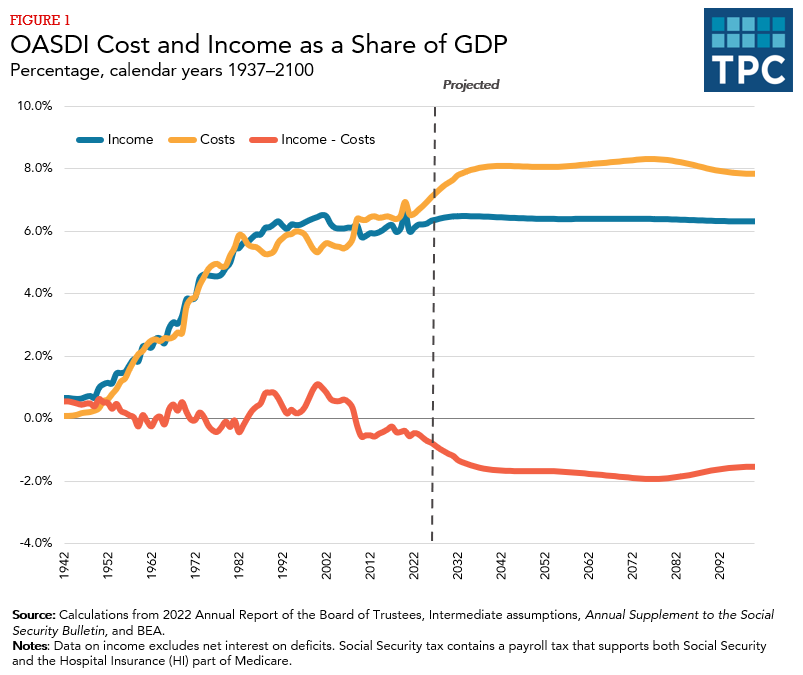

Both the OASI and DI trust funds face shortfalls as benefits currently exceed the taxes paid into their combined total. In recent years, costs (mainly benefits) of the combined OASDI trust fund have been exceeding income even when including interest payments from the Treasury(Table 1). However, excluding interest, the combined trust fund has been running deficits since 2010 (see Figure 1). In the 2023 Trustees’ Report, Social Security’s actuaries projected that the DI trust fund could maintain solvency by itself but the OASI trust fund will be exhausted by 2033, and the combined trust funds by 2034. If either event occurs, the Social Security Administration will only be able to pay a portion of benefits from payroll and other trust fund taxes collected—about three-quarters of promised benefits in the case of OASI.

When the DI fund came close to depletion in 1994, Congress diverted some of the OASI fund’s payroll tax receipts to the DI fund to maintain its solvency. Legislators took this step again in 2015, transferring funds from the OASI trust fund to extend the DI fund’s solvency, but in so doing advanced the date when the OASI fund would be exhausted.

To restore long-term trust fund solvency, policymakers will need to change Social Security through some combination of raising the payroll tax rate, reducing the rate of growth of benefits for future retirees, and tapping other sources of revenue. Research shows that both lifetime benefits and taxes increase from generation to generation, implying that any reduction in scheduled benefits can still leave future retirees with higher lifetime benefits than current retirees (Steuerle and Quakenbush 2018), although it does mean that annual benefits will be a lower portion of their average annual wages. Closing the ever-growing gap between benefits relative to taxes require policy changes.. Acting sooner rather than later will make those adjustments less dramatic when they occur and reduce the burden on future generations.

Updated January 2024

Congressional Research Service. 2022. Social Security: The Trust Funds. Washington, DC.

Social Security Administration. 2023 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds. Washington, DC.

Steuerle, C. Eugene and Karen E. Smith. 2023. “Social Security and Medicare Lifetime Benefits and Taxes.” Washington, DC: Urban Institute.