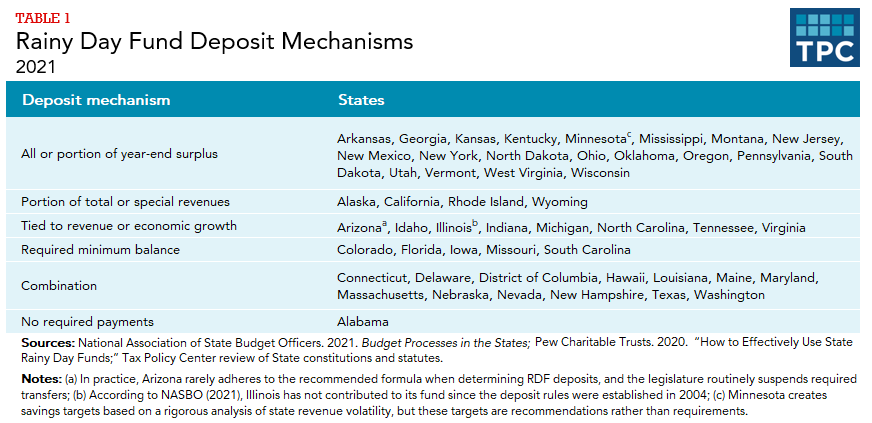

Rainy day funds, also known as budget stabilization funds, allow states to set aside surplus revenue for use during unexpected deficits. Every state has some type of rainy day fund, though deposit and withdrawal rules vary considerably.

Sources of Funding

States finance their reserve funds differently (table 1). Most allow some or all of their year-end surplus to flow to the rainy day fund (RDF), but some states require a flat contribution out of total revenue or a special revenue source. California, for example, dedicates a portion of its capital gains tax revenue to its budget stabilization account. Similarly, natural resource–rich states like Texas and Louisiana dedicate a portion of oil extraction revenues to various reserve funds, in combination with other deposit mechanisms.

A handful of states tie their reserve accounts to either revenue or economic growth. Indiana, for example, ties its deposits to personal income. Arizona also ties its deposits to a personal income growth formula, but the legislature must authorize the transfer and in practice rarely adheres to the recommended formula. Other states require specified set-asides until the fund reaches its minimum required balance. A few states replenish their funds with discretionary appropriations as part of the budget process, but regular contributions are not automatic or required in these states. Except for the few states (such as Colorado) required to remit surplus revenues to voters, most states can also carry additional general fund surpluses into the following fiscal year once any RDF funding requirements are met.

Current Fund Balances

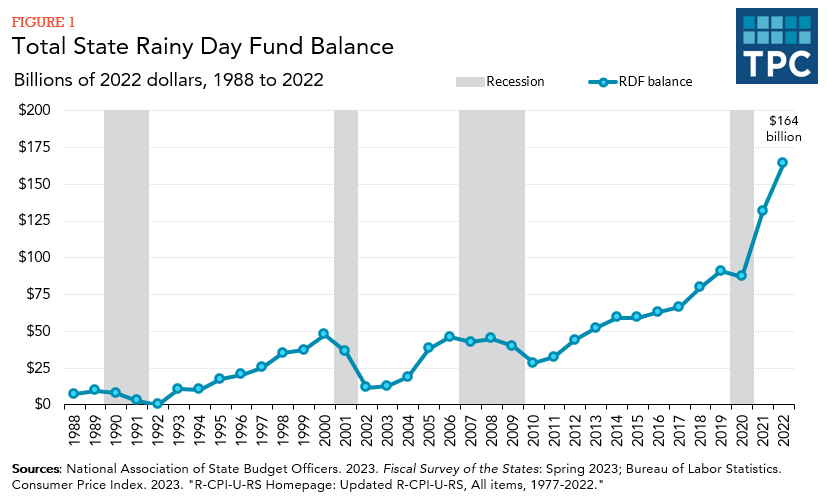

According to the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO), the total balance across all states’ rainy day funds in fiscal year 2022 reached an all-time high of $164 billion (figure 1). This is, in part, because of stronger-than-anticipated revenue growth leading to substantial budgetary surpluses in most states in fiscal years 2021 and 2022.

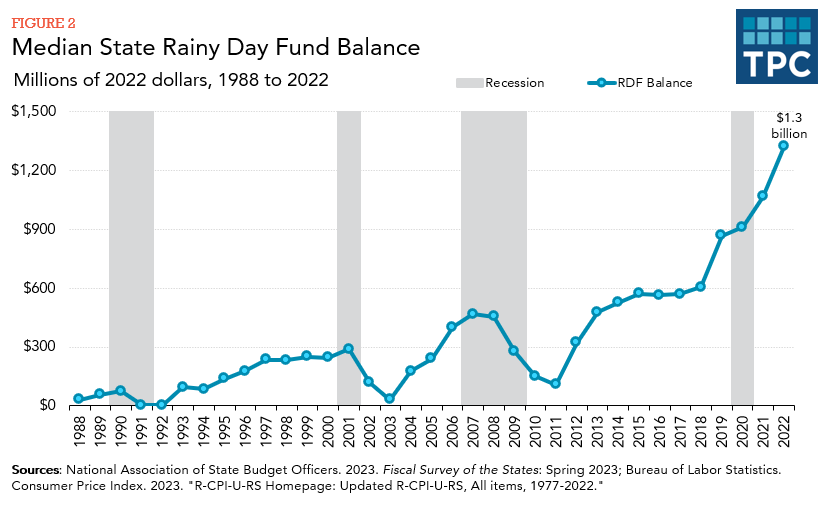

The median balance was also at a historic high of $1.3 billion in fiscal year 2022 (figure 2).

California ($76 billion) had the highest state rainy day fund balance in 2022; its balance alone contributed 46 percent of the nation’s total. The next highest balances were in Texas ($11 billion), Massachusetts ($7 billion), and Georgia ($5 billion). Per NASBO, New Jersey recorded $0 in its state rainy day fund balance in 2022; the next lowest balances were in Montana ($118 million), New Hampshire ($160 million), and Vermont ($266 million).

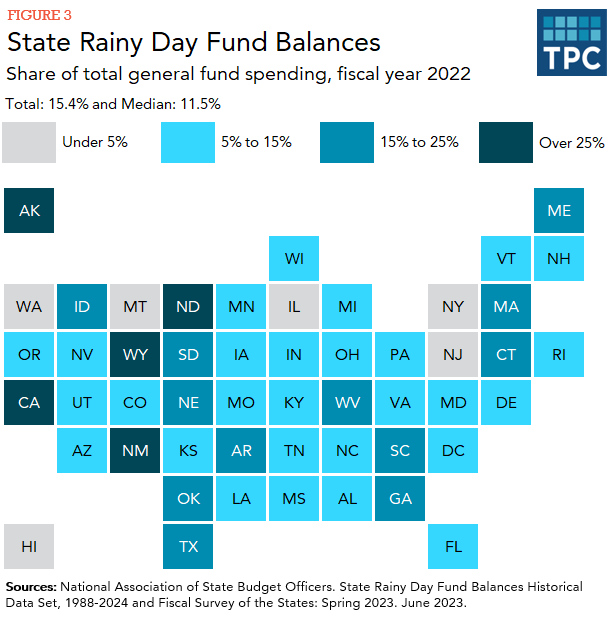

As a share of total general fund spending in fiscal year 2022, Wyoming (96 percent), Alaska (48 percent), New Mexico (38 percent) and California (34 percent) had the highest state rainy day fund balances (figure 3). Besides New Jersey, Washington (1.2 percent), Illinois (1.6 percent), Hawaii (3.7 percent), and New York (3.9 percent) had the lowest fund balances as shares of their respective spending.

Use of Funds

In most states, the RDF is dedicated to closing deficit gaps in the current year or maintaining government spending when revenues are projected to decline. However, withdrawal rules vary. Some states include transfers from the rainy day fund to the general fund in normal appropriations bills, while others require an emergency declaration or a supermajority (e.g., three-fifths or two-thirds) of the legislature to make a transfer. Several states can use the RDF to cover short-term cash flow gaps. Money is transferred to the general fund and must be paid back by the end of the fiscal year.

In addition to an RDF that can be used for general purposes during a fiscal crisis, some states have reserve funds available for only specific uses. For example, 37 states and the District of Columbia have a reserve account dedicated to disaster recovery. Other states have separate reserve funds for education or Medicaid spending, designed to cover shortfalls in these vital programs. Deposit and withdrawal rules for these supplemental reserve accounts may vary considerably from the rules governing the state’s primary RDF.

Caps on Fund Balances

Forty-one states and DC cap the balances of their funds. The cap is typically a percentage of either revenues or expenditures, although some states have more complex formulas for determining maximum fund size. Most states that finance their RDF with operating surpluses stop transfers once the cap has been reached, allowing the surplus to remain in the general fund. A few re-direct those operating surpluses to other funds for special projects or taxpayer relief. Maine, for example, after transferring the required fixed amounts to several other reserve funds, directs 80 percent of the remaining surplus to its budget stabilization fund and the remaining 20 percent to its tax relief fund for residents. If the RDF is at its cap, excess surplus flows to the tax relief fund.

Goal of Funds: Mitigating Fiscal Crises

An economic downturn can cause significant fiscal stress for states because, without changes in policy, revenues decline even as demands on programs such as unemployment insurance and Medicaid increase. Savings in rainy day funds help states weather a fiscal downturn with fewer expenditure cuts. For example, the balances of state RDFs declined significantly after each of the last three recessions, but states have gradually built them back up each time (figures 1 and 2).

Capping the amount in the RDF is a sensible approach to preventing the unnecessary build-up of restricted funds, but the cap must be set appropriately. Before the Great Recession, a typical rule of thumb was to maintain at least 5 percent of total expenditures or revenues in reserves. States that cap out at 5 percent or less, therefore, may find reserves inadequate to close fiscal gaps. Currently, nine of the 41 states with caps, as well as the District of Columbia, specify caps of 5 percent or less.

Many states have reconsidered the 5 percent rule since the Great Recession, as even states with robust prerecession RDFs exhausted much of their reserves. The Government Finance Officers Association now recommends states set aside at minimum two months of operating expenditures (i.e., roughly 16 percent of total general fund spending). Sixteen states had RDF balances at or above 16 percent at the end of 2022. In another approach, also recommended by the Government Finance Officers Association and others, some states have begun to tie and tailor their caps and deposit mechanisms to their own revenue volatility.

RDFs are an important tool for states to avoid sharp cuts in spending or tax increases when they are hurting economically. It is generally recommended that states mitigate fiscal and economic volatility by pairing strong balanced budget requirements with robust RDFs. Moreover, states should design their RDF deposit mechanisms and caps with an understanding of their revenue volatility.

Updated January 2024

Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. 2019. “Building State Budgets: Effective Process and Practice.” Washington, DC.

Randall, Megan. 2017. “How Much Rainier Does It Need to Get for Texas to Use Its Rainy Day Fund?.” Urban Wire (blog). Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Randall, Megan, and Kim Rueben. 2017 “Sustainable Budgeting in the States: Evidence on State Budget Institutions and Practices.” Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Rueben, Kim, and Megan Randall. 2017. “Budget Stabilization Funds: How States Save for a Rainy Day.” Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

McNichol, Elizabeth. 2014. “When and How Should States Strengthen Their Rainy Day Funds?.” Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Pew Charitable Trusts. 2014. “Building State Rainy Day Funds: Policies to Harness Revenue Volatility, Stabilize Budgets, and Strengthen Reserves.” Washington, DC: Pew Charitable Trusts.

Volcker Alliance. 2017. “Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting.” New York, NY.