Credits reduce taxes directly and do not depend on tax rates. Deductions reduce taxable income; their value thus depends on the taxpayer’s marginal tax rate, which rises with income.

Tax Credits

Tax credits are subtracted directly from a person’s tax liability; they therefore reduce taxes dollar for dollar. Credits have the same value for everyone who can claim their full value.

Most tax credits are nonrefundable; that is, they cannot reduce a filer’s income tax liability below zero. As a result, low-income filers often cannot receive the full benefit of the credits for which they qualify. For example, the child and dependent care credit is nonrefundable, so a married couple with income under $27,700 in tax year 2023 would not be able to use the credit because they have no income tax liability.

Some tax credits, however, are fully or partially refundable: if their value exceeds income tax liability, the tax filer is paid the excess. The earned income tax credit (EITC) is fully refundable; the child and other dependent tax credit (commonly referred to as the child tax credit, or CTC) is refundable only if the filer’s earnings exceed a $2,500 threshold. The refundable portion of the CTC is commonly called the Additional child tax credit.

Most Popular Tax Credits

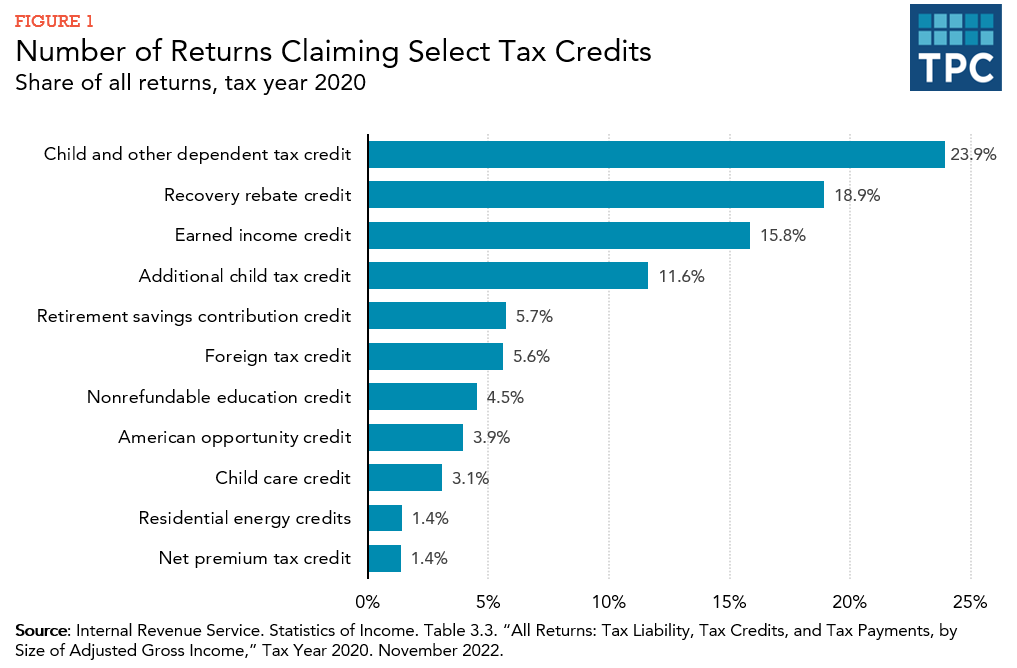

The CTC is the most commonly claimed credit, showing up on nearly a quarter of 2020’s tax returns (24 percent). The EITC was claimed on about 16 percent of tax returns. The “recovery rebate credit,” claimed by 19 percent of tax returns in 2020, was part of the federal government’s effort to provide economic relief during the COVID-19 pandemic, accounting for taxpayers who did not receive their full rebates in the first or second round Economic Impact Payments (figure 1).

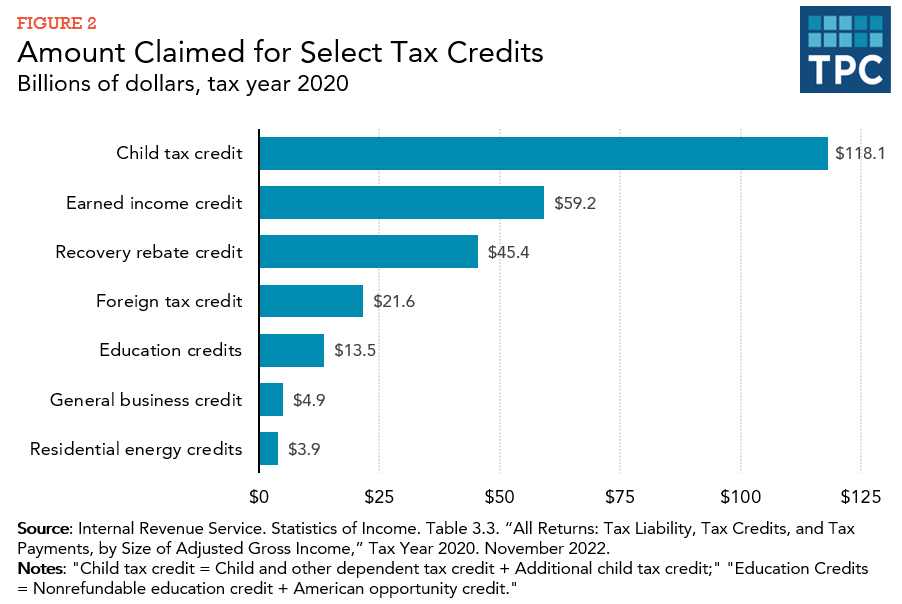

In terms of overall costs for tax year 2020, the CTC (including the refundable portion) is also the costliest tax credit, totaling about $118 billion, followed by the EITC ($59 billion) (figure 2).

The amount claimed in tax credits will change after the expiration of the individual income tax provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) at the end of 2025. According to the Joint Committee on Taxation, under current law, the total costs of the CTC will drop significantly, from nearly $119 billion in tax year 2025 to about $62 billion in tax year 2026. Whereas, the EITC will gradually increase over the coming years to cost $77 billion in 2026. Those two will remain the largest tax credits.

Tax Deductions

Tax filers have the choice of claiming the standard deduction or itemizing deductible expenses from a list that includes state and local taxes paid, mortgage interest, and charitable contributions. In either case, filers decrease their taxable income by the amount of the allowed deduction.

Tax filers may also claim some deductions in addition to the standard deduction or itemized deductions. These deductions (technically “adjustments to income”) are sometimes called “above the line” deductions because they come before the line that determines adjusted gross income on tax return form 1040. Adjustments to income include contributions to individual retirement accounts, educator expenses, and interest on student loans.

Further, there are also so-called “between the line” deductions, which reduce taxable income, but not adjusted gross income. These include the deduction for qualified business income (QBI), which reduces taxable income but can be claimed irrespective of whether or not a taxpayer itemizes. These deductions do not affect tax benefits that phaseout as adjusted gross income increases.

The value of all deductions, itemized or otherwise, depends on the taxpayer’s tax liability and marginal tax rate. A deduction cannot reduce taxable income below zero, so taxpayers lose the value of excess deductions once they reach that limit. Taxpayers can, however, carry over some unused deductions into future years. By reducing taxable income, a deduction lowers tax liability by the amount of the deduction times the taxpayer’s marginal tax rate. Deductions are thus worth more to taxpayers in higher tax brackets. For example, a $10,000 deduction reduces taxes by $1,200 for people in the 12 percent tax bracket, but by $3,200 for those in the 32 percent tax bracket.

The alternative minimum tax (AMT) disallows the standard deduction and some itemized deductions. For example, AMT taxpayers may not deduct state and local tax payments. The AMT reduces but does not eliminate other deductions. After TCJA was passed in 2017, the AMT has impacted a very small share of taxpayers.

Updated January 2024

Holt, Steve. 2006. “The Earned Income Tax Credit at Age 30: What We Know.” Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Maag, Elaine. 2006. “Tax Credits, the Minimum Wage, and Inflation.” Tax Policy Issues and Options brief 17. Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.