An automatic 401(k) enrolls workers automatically, assigning them a default contribution rate and allocation of funds that they are free to change later.

An automatic 401(k) is one that automatically enrolls workers in the plan, rather than requiring them to sign up. Eligible workers are assigned a default contribution rate—often 3 percent of wages—and a default allocation of funds contributed to the retirement account. As with traditional 401(k)s, workers are still in control; they can change the default contribution rate and allocation or opt out entirely. The main difference: with an automatic 401(k), inaction on the worker’s part will automatically result in the worker saving for retirement.

This difference is, as a practical matter, significant. With traditional 401(k) plans, workers must decide whether to sign up, how much to contribute, how to allocate their investment funds, how often to rebalance their portfolios, what to do with the accumulated funds when they change jobs, and when and in what form to withdraw the funds during retirement. These decisions are difficult, and many workers, daunted by the complexity, either make inappropriate choices or never sign up at all.

With an automatic 401(k), sometimes called an “opt-out plan,” unless workers make the active decision not to participate, each stage of the savings and investment allocation process is automatically set at a pro-saving default. Workers can choose to override any of these choices, but the inertia that discourages so many from opting into a traditional 401(k) is now likely to keep them on the default path.

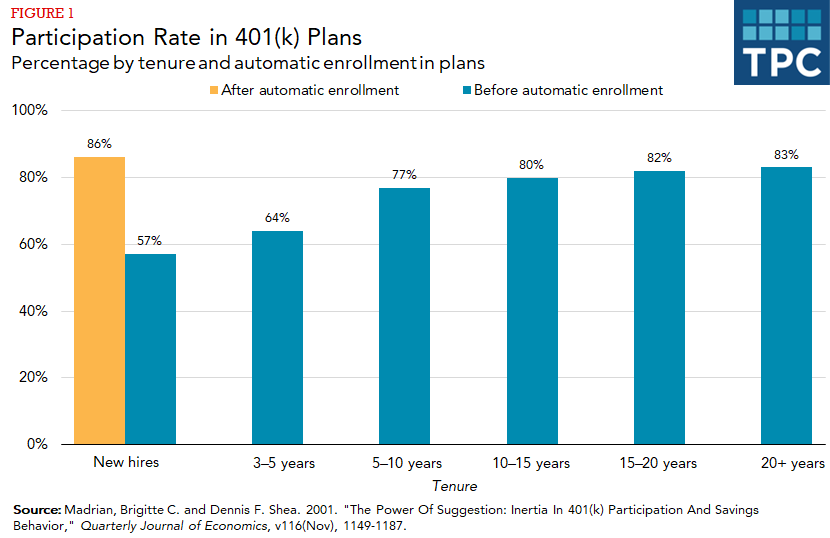

Figure 1 shows that automatic enrollment raises 401(k) participation rates among new hires. This is especially true for women, minority groups, and low earners.

The automatic escalation of default contributions over time raises overall contributions to 401(k)s relatively painlessly, as employees become accustomed to deferring receipt of a portion of their pay. The gradual escalation also helps ensure that inertia does not keep employees at a default contribution rate lower than the rate they might have chosen without the default.

Updated January 2024

Benartzi, Shlomo, and Richard Thaler. 2004. “Save More Tomorrow: Using Behavioral Economics to Increase Employee Saving.” Journal of Political Economy 112(1): S164–S187.

Chetty, Raj, John Friedman, Soren Leth-Petersen, Torben Heien Nielsen, and Tore Olsen. 2014. “Active vs. Passive Decisions and Crowd-Out in Retirement Savings Accounts: Evidence from Denmark.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 129 (3): 1141–1219.

Gale, William G., J. Mark Iwry, and Peter R. Orszag. 2005. “The Automatic 401(k): A Simple Way to Strengthen Retirement Saving.” Policy brief 2005-1. Washington, DC: Retirement Security Project.

Madrian, Brigitte, John Beshears, James Choi, and David Laibson. 2013. “Simplification and Saving.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 95: 130–45.