Taxpayers subtract both refundable and nonrefundable credits from the income taxes they owe. If a refundable credit exceeds the amount of income taxes owed, the difference is paid as a refund. If a nonrefundable credit exceeds the amount of income taxes owed, the excess is lost.

Refundable Versus Nonrefundable Tax Credits

The maximum value of a nonrefundable tax credit is capped at a taxpayer’s income tax liability. In contrast, taxpayers receive the full value of their refundable tax credits. The amount of a refundable tax credit that exceeds income tax liability is refunded to taxpayers.

Most tax credits are nonrefundable. Notable exceptions include the fully refundable earned income tax credit (EITC), the premium tax credit for health insurance (PTC), the refundable portion of the child tax credit (CTC) known as the additional child tax credit (ACTC), and the partially refundable American opportunity tax credit (AOTC) for higher education. With the EITC, PTC, and ACTC, taxpayers calculate the value of these credits and receive the credit first as an offset to taxes owed, with any remainder paid out as a refund. With the AOTC, if the credit fully offsets taxes owed, 40 percent of the remainder can be paid out as a refund.

Budget Treatment of Refundable Versus Nonrefundable Tax Credits

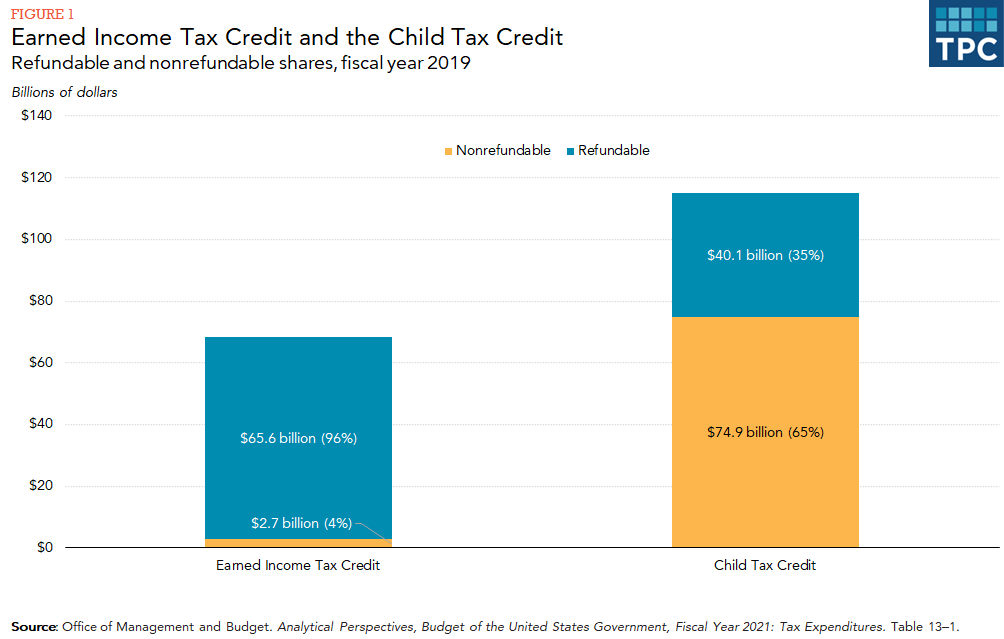

The federal budget distinguishes between the portion of a tax credit that offsets income tax liability and the portion that is refundable, classifying the latter as an outlay. Most of the EITC—an estimated $65.6 billion of the 2019 total of $68.3 billion—was refunded. Much less of the child tax credit ($40.1 billion out of $115 billion) was refunded (figure 1). The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act substantially changed the child tax credit for 2018 through 2025, including doubling the maximum credit to $2,000 per child under age 17 while limiting the maximum refundable amount to $1,400 (this amount will increase with inflation up to $2,000.) The TCJA also created a nonrefundable credit worth $500 per dependent not qualifying for the full $2,000 credit. Before this change, expenditures on the child tax credit totaled $54.3 billion, with just over half delivered as refundable credits. In FY2019, expenditures from the CTC totaled an estimated $115 billion; of which 35 percent was refundable.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Refundable Credits

Proponents of refundable credits argue that only by making credits refundable can the tax code effectively carry out desired social policy. This is especially true for the EITC and the CTC: if the credits were not refundable, low-income households most in need of assistance would not benefit from them. Furthermore, allowing credits only against income tax liability ignores the fact that most low-income families also incur payroll taxes.

Opponents of refundable credits, for their part, raise a host of objections:

- The tax system should collect taxes, not redistribute income.

- The government should not use the tax system to carry out social policies.

- Refundable credits increase administrative and compliance costs, and enable fraud.

Updated January 2024

Batchelder, Lily L., Fred T. Goldberg, and Peter R. Orszag. 2006. “Efficiency and Tax Incentives: The Case for Refundable Tax Credits.” Stanford Law Review 59 (23): 2006.

Sammartino, Frank, Eric Toder, and Elaine Maag. 2002. “Providing Federal Assistance for Low-Income Families through the Tax System.” Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.