The tax expenditure budget displays the estimated revenue losses from special exclusions, exemptions, deductions, credits, deferrals, and preferential tax rates in federal income tax law.

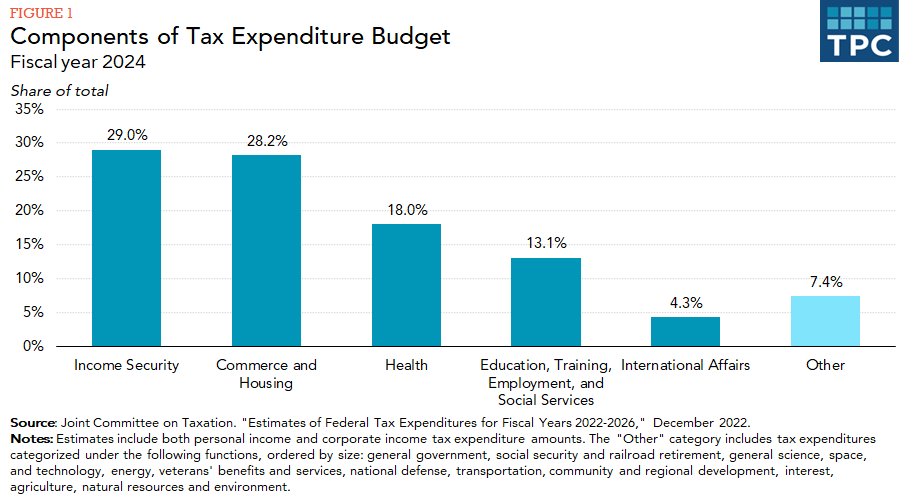

Every year, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) publish lists of tax expenditures. These lists, sometimes called the Tax Expenditure Budgets, enumerate the estimated revenue losses attributable to preferences in the tax code the agencies describe as exceptions to “normal” or “reference” provisions of the income tax law (figure 1).

Tax expenditures reduce the income tax liabilities of individuals and businesses that undertake activities Congress specifically encourages. For example, the deduction for charitable contributions reduces tax liability for people who itemize on their tax returns rather than take a standard deduction and donate to qualifying charitable organizations. Tax expenditures can also reduce tax liability for individuals Congress wishes to assist. For example, a portion of Social Security benefits received by retired or disabled people is exempt from federal income tax.

The Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974 requires that the budget include estimates for tax expenditures, but only for provisions that affect the federal income taxes of individuals and corporations. The government could, but does not, provide lists of tax expenditures for payroll taxes, excise taxes, and other taxes, although OMB does estimate (in footnotes) the effects on payroll tax receipts of income tax expenditures. At one time, an estate tax expenditure budget was produced by the US Department of the Treasury and published by OMB.

Both the Office of Tax Analysis in the Treasury and the JCT estimate tax expenditures annually. The items included in each, along with their estimated values, are generally similar but do not always match. OMB publishes the Office of Tax Analysis’s estimates in its Analytical Perspectives volume that accompanies each year’s Budget of the US Government.

The budget generally treats tax expenditures as revenue losses instead of as spending. Accordingly, only the portion of refundable tax credits, such as the earned income tax credit, that offsets individuals’ positive income tax liabilities are shown in OMB’s tables as tax expenditures, while the portion that is refundable and exceeds tax liabilities is counted in spending. On the other hand, JCT’s tables include both the revenue loss and outlay effects of refundable credits. Both OMB and JCT display the outlay effects in footnotes.

JCT’s tax expenditures for fiscal 2024 (including outlay effects) added up to $1.8 trillion. The combined revenue loss for all provisions does not equal the sum of the losses for each provision because of how the provisions interact. For example, eliminating one exemption from taxable income would push taxpayers into higher-rate brackets, thereby increasing the revenue loss from remaining exemptions.

Toder and Berger (2019) estimated that the actual combined revenue loss from all individual tax expenditures in 2019 was about 5 percent larger than the amount computed by summing individual tax expenditures—though for one subcategory, itemized deductions, the total revenue loss is less than the sum of losses from the separate deductions.

Some tax expenditures effectively function like direct expenditures even though they appear as tax breaks, because programs with similar effects could be structured as outlays (Burman and Phaup 2011). An example is the tax credit for renewable energy investment, which could be structured as grants from the Department of Energy. Other expenditures have no direct spending analogy, but can instead be viewed as departures from an income tax with a comprehensive base. Marron and Toder (2013) estimate that provisions that could be viewed as spending substitutes then amounted to over 4 percent of gross domestic product.

Complicating matters is that the ideal administrative agency for a tax subsidy might or might not be the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), regardless of classification. For example, because the earned income credit is a direct cash transfer that is based largely on wage reporting, the IRS might serve appropriately as the administrative agency. For other tax expenditures that promote specific activities, administration by an agency with the required programmatic expertise may be preferable.

Like most mandatory programs (or entitlements) on the spending side of the budget, most tax expenditures do not go through a direct appropriation process each year and are available with no budget ceiling to all who qualify. Expenditure costs change with the growth of the economy, changes in the quantities and prices of subsidized activities, and—for some provisions—changes in marginal tax rates applied to individual and corporate income and other tax law provisions. For example, the cost of the mortgage interest deduction varies with the volume of home mortgage debt outstanding, the level of interest rates, marginal tax rates applied to the taxable income of borrowers, the size of the standard deduction, and limitations on other itemized deductions.

Updated January 2024

Burman, Leonard E., and Marvin Phaup. 2011. “Tax Expenditures, the Size and Efficiency of Government, and Implications for Budget Reform.” Working Paper 17268. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Marron, Donald, and Eric Toder. 2013. “Tax Policy and the Size of Government.” Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Toder, Eric J., and Daniel Berger. 2019. “Distributional Effects of Individual Income Tax Expenditures After the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.” Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Congressional Budget Office. 2021. “The Distribution of Major Tax Expenditures in 2019.” Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office.