The gross tax gap is the difference between total taxes owed and taxes paid voluntarily and on time.

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) estimates that over the past 30 years, the tax gap has fluctuated in a narrow range—15 to 18 percent of total tax liability. Some view the tax gap as a possible major revenue source that could be used to close the federal budget deficit without raising taxes. In practice, though, Treasury and the Congressional Budget Office have differed greatly in their estimates of the revenue gains from proposals to improve enforcement, and neither have projected the impact of those proposals on the size of the tax gap.

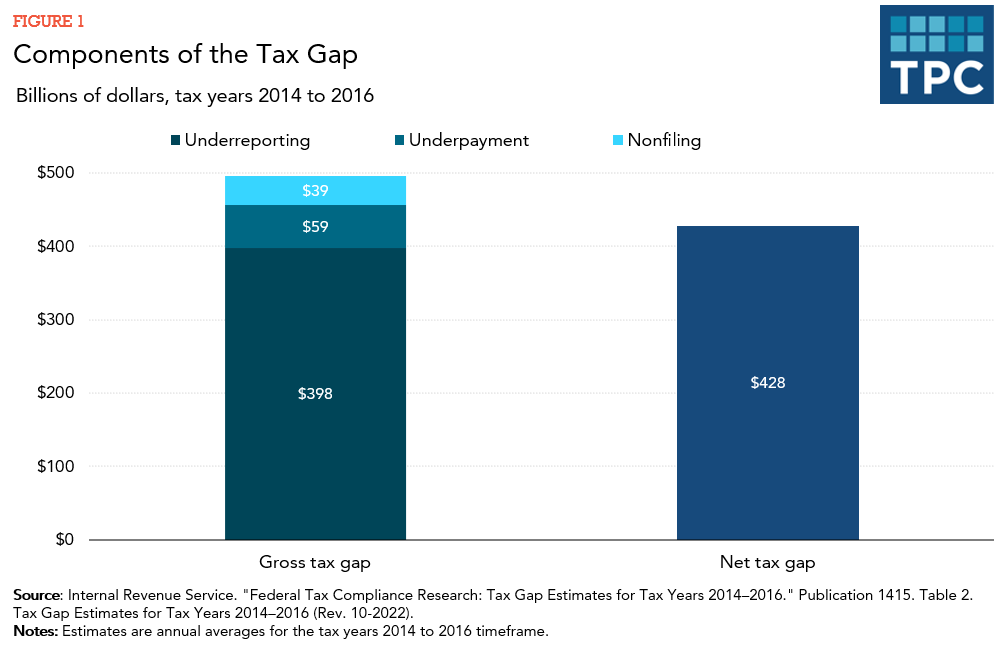

The most recent IRS tax gap report was released in 2022 and covered tax years 2014–16. For those years, the IRS reported an average annual gross tax gap of $496 billion (15 percent of total tax liability). Of this, the IRS will eventually recover $68 billion through voluntary late payments and enforcement activities, resulting in an average annual net tax gap of $428 billion (or about 13 percent of total tax liability).

Underreporting on timely filed tax returns made up the bulk of the tax gap: $398 billion, or 80 percent of the gross tax gap (figure 1). Failure to file a tax return (nonfiling) and underpayment of reported taxes accounted for the remaining 20 percent.

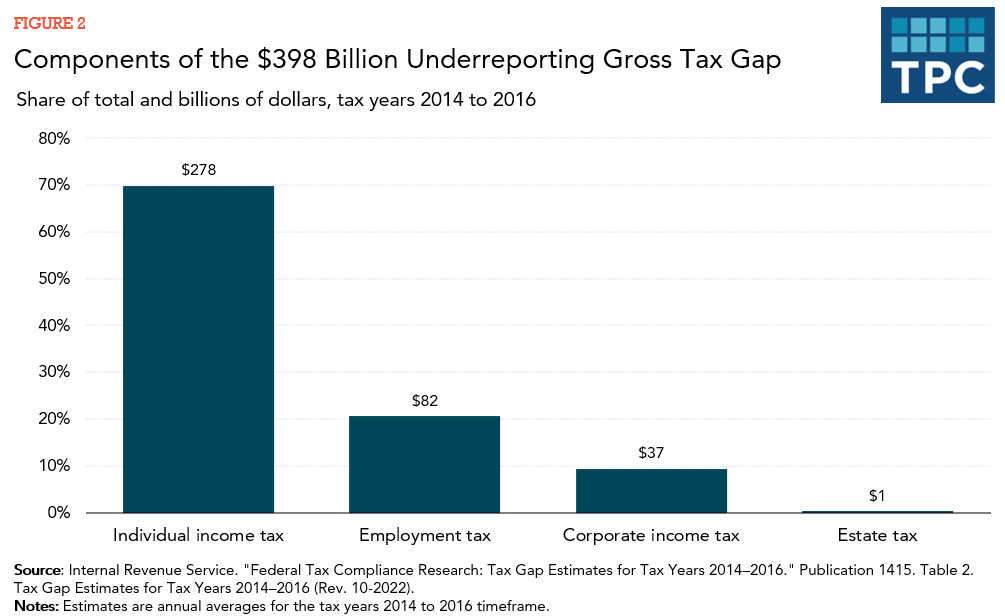

Underreporting on individual income tax returns alone was $278 billion (figure 2), about 70 percent of the underreporting tax gap in 2014–16. About 47 percent of the underreported individual income tax was owed on business income, which the IRS has no easy way to verify independently. About 21 percent of the total underreporting gap was due to employment taxes, mostly because of underreporting of self-employment income taxes. Another 9 percent of the underreporting gap was attributable to corporate income tax and only 0.3 percent to the estate tax.

Individual taxpayers failed to report about 55 percent of income from sources for which there was little or no information reporting, such as sole proprietorships. In contrast, only 6 percent of income from easily verified sources—interest, dividends, and pensions—was unreported. When income was subject to both information returns and tax withholding, as with wages, only about 1 percent was unreported.

Efforts to Reduce the Tax Gap

The Inflation Reduction Act boosted the IRS’s ten-year budget—above its annual appropriations—by nearly $80 billion. About 57 percent of the funds were allocated to tax enforcement with the remainder distributed among IRS operations (32 percent), technological modernization (6 percent), and taxpayer services (4 percent).

Although there is a consensus among Treasury and Congressional scorekeepers that increasing funding for enforcement will raise revenues, their estimates of the direct savings (the amounts collected in audits) differ significantly. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that revenues would rise by $180 billion over the decade as a direct consequence of the increase in enforcement funds, reducing the deficit, net of the cost, by about $100 billion. In contrast, the Treasury Department initially estimated that the direct revenues would rise by about $320 billion (with net savings of $240 billion). Later, the Treasury Department released new estimates, increasing net savings to $400 billion. Those estimates incorporated assumptions about the impact of the increased enforcement on deterrence (indirect effects).

The amount of revenue collected by the initiatives may not match the reduction in the estimated tax gap. For example, some compliant taxpayers may be selected for an audit and erroneously assessed additional taxes. Investments in the IRS may, however, lead to improvements in its audit selection techniques—reducing the probability that compliant taxpayers are selected for audits, but also possibly improving the IRS researchers’ ability to detect more noncompliance when measuring the size of the tax gap.

Updated January 2024

Burke, Kathleen, Shannon Mok, and Joseph Rosenberg. The U.S. Tax Gap and Revenue Estimates from Increased Funding for the Internal Revenue Service. Presentation to the Brazilian Tax and Customs Administration. December 7, 2022.

Erard, Brian, and Jonathan Feinstein. “The Individual Income Reporting Gap: What We See and What We Don’t.” IRS Research Bulletin: Proceedings of the 2011 IRS/TPC Research Conference, 129–42. Publication 1500 (rev 4-2012). Washington, DC: Internal Revenue Service.

Erard, Brian, Mark Payne, and Alan Plumley. 2012. “Advances in Non-Filing Measures.” Washington, DC: Internal Revenue Service.

Holtzblatt, Janet and Jamie McGuire. 2016. “Factors Affecting Revenue Estimates of Tax Compliance Proposals.” Congressional Budget Office Working Paper 2016-05.

Holtzblatt, Janet and Jamie McGuire, 2020. “Effects of Recent Reductions in the Internal Revenue Service’s Appropriations on Returns on Investment.” IRS Research Bulletin: Proceedings of the 2019 IRS/TPC Research Conference, 129–143. Publication 1500 (rev 6-2020). Washington, DC: Internal Revenue Service.

Johns, Andrew and Joel Slemrod. 2010. “The Distribution of Income Tax Noncompliance.” National Tax Journal 63 (3): 397–418.

Mazur, Mark J., and Alan Plumley. 2007. “Understanding the Tax Gap.” National Tax Journal 60 (3): 569–76.

Toder, Eric J. 2007. “What Is the Tax Gap?” Tax Notes. October 22.

US Department of the Treasury. 2001. The American Families Plan Tax Compliance Agenda. May.

Yellen, Janet. 2021. Letter to Ways and Means Committee Chairman. September 14.