Provisions of the federal income tax that subsidize domestic production of fossil fuels include the expensing of exploration, development, and intangible drilling costs; the use of percentage depletion instead of cost depletion to recover drilling and development costs of oil and gas wells and coal mines; and numerous smaller incentives for production and distribution of oil, coal, and natural gas.

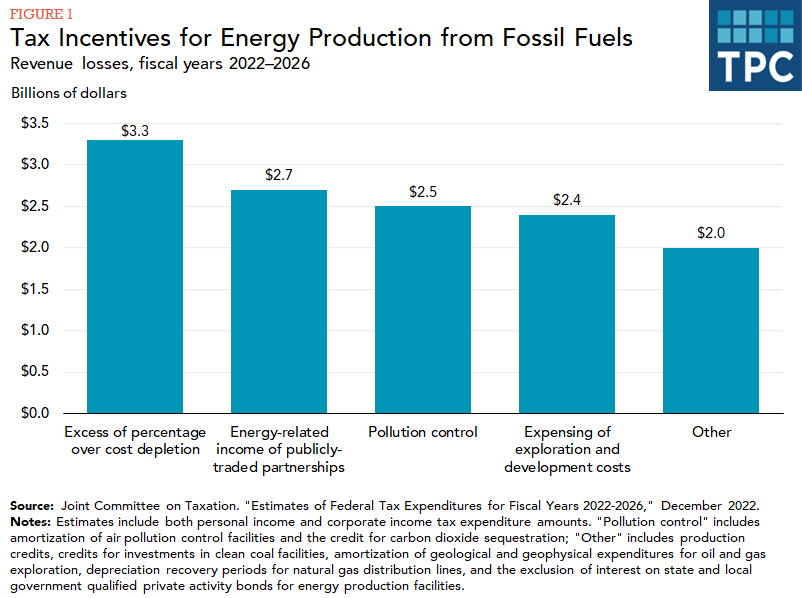

Tax subsidies for oil, gas and coal development are expected to reduce federal revenue by $12.9 billion from 2022 to 2026 (figure 1). The three largest subsidies are for excess of percentage over cost depletion ($3.3 billion), exceptions for publicly-traded partnership with qualified income derived from certain energy-related activities ($2.7 billion), pollution control ($2.5 billion), and expensing of exploration and development costs ($2.4 billion).

Excess of percentage over cost depletion allows producers to deduct a fixed percentage of gross revenue as capital expenses each year, without regard to how much they have invested. By contrast, conventional cost depletion allows deduction of actual costs as the resources from a well or mine are depleted. Federal tax law allows independent producers—but not integrated companies—to deduct 15 percent of gross revenue from their oil and gas properties as percentage depletion.

Exploration and development costs include labor and materials needed for drilling and developing oil and gas wells and coal mines. Independent oil and gas producers (i.e., those without related refining and marketing operations) may deduct these costs from income in the year incurred, even though, as capital investments, they produce returns over many years. Integrated oil and gas companies may deduct 70 percent of these costs in the first year and recover the remaining 30 percent over the next five years.

Other tax subsidies for fossil fuels include: publicly traded partnerships, which allow pass-through oil and gas partnerships to publicly list their shares (a privilege generally reserved for higher-taxed C-corporations); amortization of geological and geophysical expenditures associated with oil and gas exploration; accelerated depreciation of natural gas infrastructure; investment credits for clean coal facilities; and energy production credits for coal.

Subsidizing investment in fossil fuel development diverts capital from investments in other assets with higher pretax yields. Several studies have found that the effective marginal tax rate—the extent to which all applicable tax provisions reduce the after-tax return on new investment—is much lower for oil, gas, and coal development than for other assets.

Subsidizing domestic production of fossil fuels is inconsistent with the policy goal of reducing fossil fuel use to counter global climate change. Supporters justify these tax incentives as a means of reducing US dependence on imported oil, but the incentives also encourage more rapid exhaustion of domestic supplies, which may increase dependence on imports in the long run.

In general, the adverse effects of the incentives on climate change are likely minor, because any increase in domestic production they induce mostly displaces imports rather than raising domestic fuel consumption. Some research concludes that the incentives reduce the world market price of oil by less than 0.1 percent and thus have little effect on consumption. A recent study by the National Academy of Sciences (Nordhaus et al, 2013) finds that subsidies for oil and gas production may slightly reduce greenhouse gas emissions by accelerating the conversion of electricity production from coal to natural gas.

A relatively small subsidy is offered for investment in carbon capture technologies, which reinject carbon emissions from fossil fuel combustion into the ground. Proponents argue that carbon capture mitigates the environmental harm from US energy consumption, which currently relies predominantly on fossil fuels. Opponents regard development of carbon capture technology as deterring full decarbonization of the US economy.

Updated January 2024

Congressional Budget Office. 2014. “Taxing Capital Income: Effective Marginal Tax Rates Under 2014 Law and Selected Policy Options.” Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office.

Gravelle, Jane. 2003. “Capital Income Tax Revisions and Effective Tax Rates.” Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

Mackie, James B., III. 2002. “Unfinished Business of the 1986 Tax Reform Act: An Effective Tax Rate Analysis of Current Issues in Corporate Taxation.” National Tax Journal 65 (2): 293–338.

Metcalf, Gilbert. 2007. “Federal Tax Policy Towards Energy.” In Tax Policy and the Economy, edited by James M. Poterba, 145–84. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Nordhaus, William D., Stephen A. Merrill, and Paul T. Beaton, eds. 2013. Effects of U.S. Tax Policy on Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Toder, Eric. 2007. “Eliminating Tax Expenditures with Adverse Environmental Effects.” Washington, DC: Brookings Institution and World Resources Institute