A small number of colleges and universities in the United States have accumulated significant wealth in the form of endowments. Because these institutions are public and private nonprofit charitable enterprises, donations to their endowments are not taxed and the assets grow free of taxes. In 2017 Congress created an exception to this practice, imposing a tax on the endowment earnings of a small number of private nonprofit colleges and universities.

The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) imposed a new tax on a small group of private nonprofit colleges and universities. Institutions enrolling at least 500 students that have endowment assets exceeding $500,000 per student (other than those assets which are used directly in carrying out the institution’s exempt purpose) pay a tax of 1.4 percent on their net investment income. The $500,000 threshold is not indexed for inflation. In 2022, the tax raised $244 million from 58 institutions.

Current Tax Treatment of Endowments

Most private nonprofit colleges and universities are exempt from taxes because of their status as 501(c)(3) organizations and their educational mission. Many of these institutions attempt to accumulate endowments—financial assets that generate income to supplement budgets and provide long-term fiscal stability. Endowments support a wide range of activities. At doctoral universities, these include graduate education and research in addition to undergraduate education.

The tax treatment of private nonprofit college and university endowments differs from the treatment of private foundations. Private foundations are tax-exempt organizations established by an individual, family, or company for charitable purposes. Unlike college and university endowments, which accrue from multiple sources over time, foundations must pay an excise tax on their net investment income (generally 2 percent but reduced to 1 percent if their distributions are growing over time). Nonoperating foundations, which are funded by a single or small group of donors and distribute money to others rather than engage themselves in charitable activities, are required to pay out at least 5 percent of their funds each year. In contrast, operating foundations can receive donations from many donors and primarily operate charitable activities themselves rather than distribute grants. They, like college and university endowments, do not have payout requirements.

Size of Endowments

Public and private colleges and universities collectively hold over $500 billion in endowment wealth, but just 23 of these institutions hold approximately 50 percent of the assets. (There are about 1,600 private nonprofit and more than 700 public four-year institutions in the United States.)

Endowments provide income that supplements tuition and fees, state appropriations, and other funding sources to support the education of undergraduate and graduate students, as well as research, public service, and other institutional activities. Endowments provide a cushion that protects institutional budgets from cyclical pressures, unanticipated changes in enrollments, and other temporary revenue disruptions.

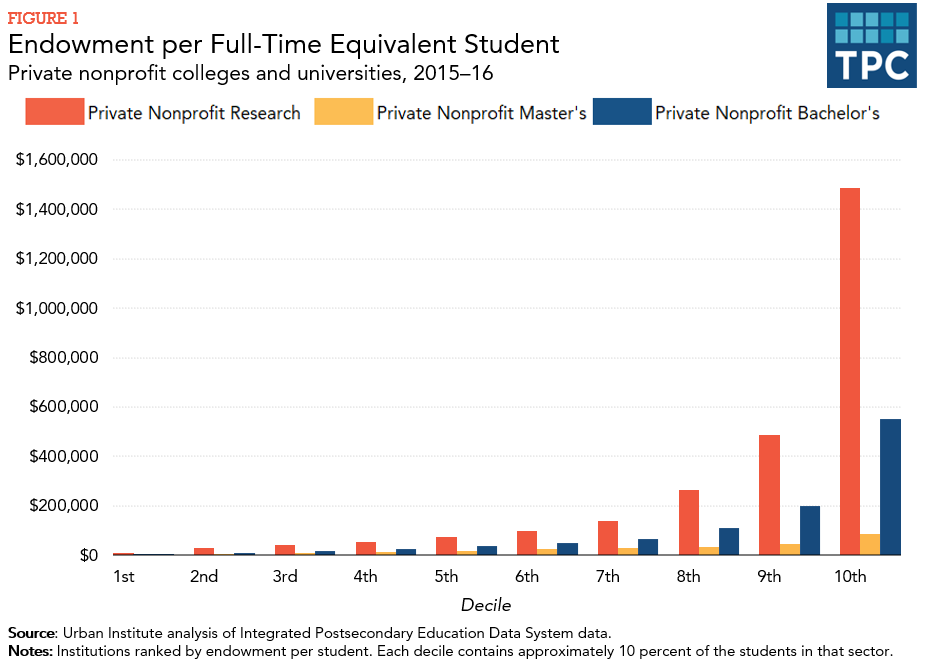

When measuring institutional strength, it is best to examine endowment per student rather than total endowment dollars (figure 1). These figures must be interpreted with caution because they do not distinguish between undergraduate and graduate students, and differences across institutions may be misleading given the differences in institutional missions. Undergraduate colleges use almost all draw (the funds added to their annual budgets from endowments) to support undergraduate education, whereas research universities use the funds to support a broader range of activities.

The endowments of the wealthiest private research universities enrolling 10 percent of students in the sector average about $1.5 million per student. The average combined endowment ($486,000 per student) for the wealthiest institutions enrolling half the students in this sector is more than 10 times the average endowment ($43,000 per student) of the institutions with the lowest endowments where the other half of this sector’s students are enrolled. Endowment wealth at private bachelor’s colleges is similarly skewed. At the master’s universities, where there is much less wealth and the gaps are smaller, the average endowment for the top half is still almost five times the average for the bottom half.

The Effect of the New Tax

While the tax generates little revenue for the federal government, it may have set a precedent for imposing further taxes on these nonprofit entities. Some members of Congress have questioned whether these wealthy institutions actually use their resources to further society’s educational goals in a meaningful way, largely because few low-income students enroll at institutions with large endowments, which have very selective admissions. In both the public and private nonprofit sectors, the higher the endowment income per student at a college or university, the lower the share of its student body receiving federal Pell grants for low- and moderate-income students.

However, the high-endowment schools do use some of their wealth to reduce the prices they charge low-income students. Low-income students who attend the best-endowed institutions benefit both from the opportunities offered and from considerably lower net tuition prices than they would pay elsewhere. Financial aid is already so generous at these institutions that the tax will not likely lower prices. Moreover, these wealthy institutions enroll fewer than 150,000 of the 4 million students in the private nonprofit sector, and 20 million postsecondary students overall.

The endowment tax is controversial. There are bipartisan efforts in Congress to repeal the tax, which is, unsurprisingly, unpopular among the higher education community. Some earlier proposals for taxing colleges and universities involved providing incentives for institutions to spend their endowments in certain ways or to modify their pricing structures. Whether it is feasible or advisable for the federal government to effect such changes, the current legislation makes no such effort, nor does it use revenues generated by the tax to further the nation’s educational goals.

Updated January 2024

Don’t Tax Higher Education Act, H.R. 5220—115th Congress (2017–2018).

Baum, Sandy, and Victoria Lee. 2018. “Understanding Endowments.” Washington DC: Urban Institute.

Congressional Research Service. 2015. “College and University Endowments: Overview and Tax Policy Options.” Washington DC.

Seltzer, Rick. 2020. “How Much Are Most Colleges Paying in Endowment Tax?.” Inside Higher Ed.