Your choice: pay the IRS now or pay them later.

Broadly speaking, there are two types of tax-favored retirement accounts: “front-loaded” accounts, such as traditional IRAs and 401(k)s, and “back-loaded” accounts, such as Roth IRAs and Roth 401(k) accounts. With front-loaded accounts, contributions are tax deductible, but withdrawals are taxed. These accounts are also called EET accounts (the contribution is exempt from taxation, the accrual of returns is exempt from taxation, and the withdrawal is taxed). In back-loaded accounts, contributions are not tax deductible, but accruals and withdrawals are tax-free. These accounts are also called TEE accounts (contributions taxed, accruals exempt, withdrawals exempt). In both types of accounts, investment returns on assets kept within the account (accruals) are untaxed.

Which is a better deal? That depends on the difference between individuals’ tax rates during their working years and during retirement. Individuals with high tax rates during their working years and lower rates during retirement benefit more from front-loaded accounts because the original contributions are deducted against high tax rates and withdrawals are taxed at lower rates. Someone who expects to be in a higher bracket in retirement would benefit more from a back-loaded account.

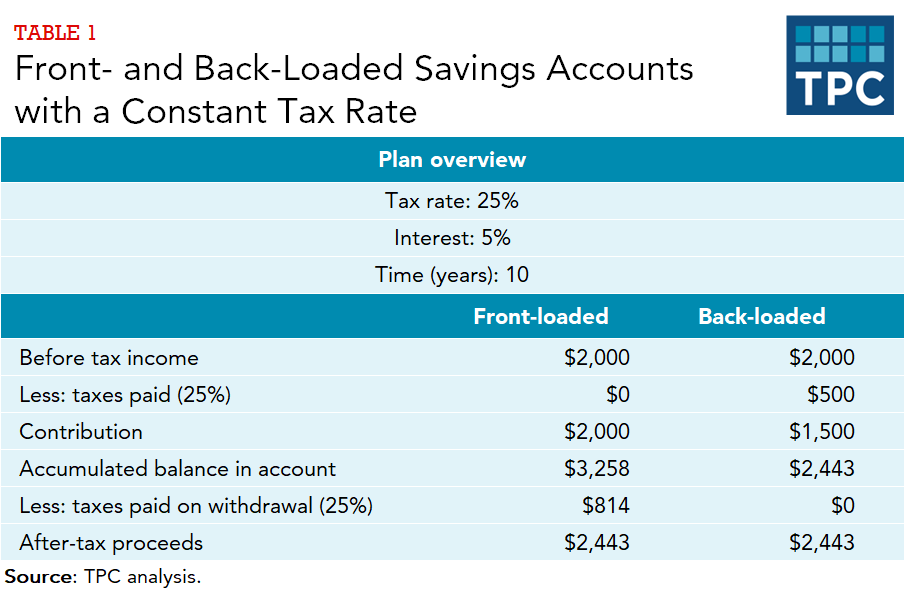

The example in table 1 shows that if tax rates during working years and retirement are the same, front- and back-loaded accounts yield the same result.

Consider a front-loaded account first. Say an individual faces a 25 percent tax rate when making both contributions and withdrawals, makes a before-tax contribution of $2,000, earns 5 percent per year, and withdraws all funds after 10 years. In a front-loaded account, the individual will be able to contribute the full $2,000. The account will accumulate interest, and after 10 years the balance will be $3,258. Upon withdrawal, the individual will pay $814 in taxes, leaving net retirement assets of $2,443. With a back-loaded account, an individual pays a 25 percent tax on $2,000 in income, leaving $1,500 to contribute to the account. With the same 5 percent return, the balance will grow to $2,443. Since no taxes will be paid on withdrawal, after-tax proceeds are $2,443, which is the same as in the front-loaded example.

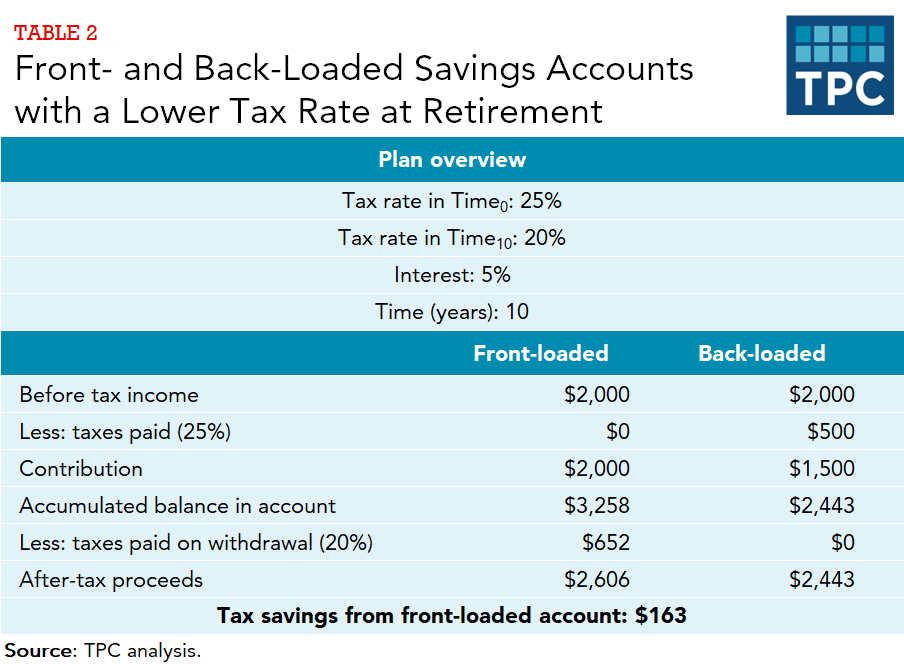

Now check out the example in table 2, in which the tax rate decreases from 25 percent during working years to 20 percent during retirement. Here, the front-loaded account will accrue $163 more than the back-loaded account, since taxes are imposed upon withdrawal, when rates are lower. Of course, the conclusion is reversed if the tax rate is higher during retirement than during working years.

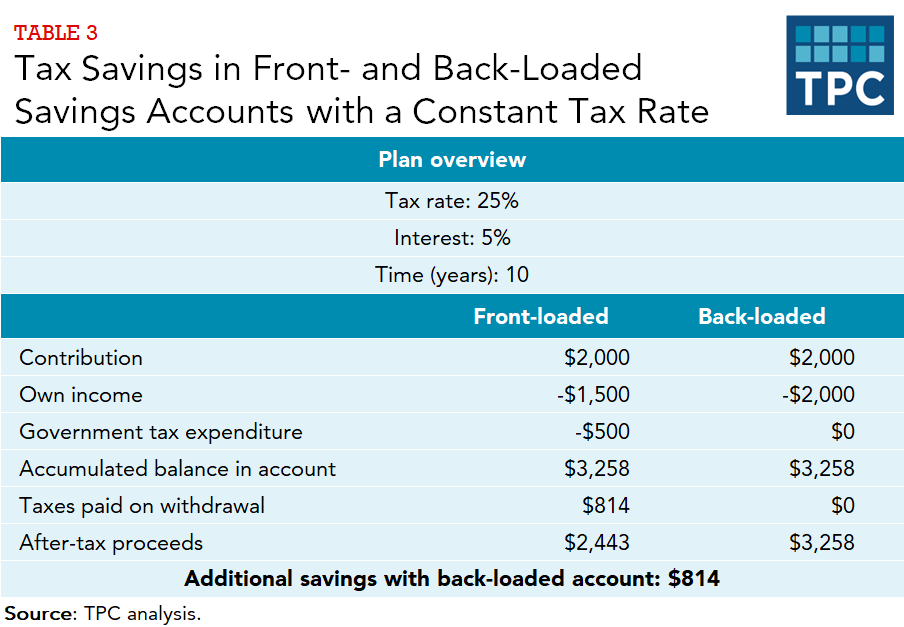

That’s not quite the end of the story, though. If the two accounts have the same contribution limit, an individual can shelter more savings in a back-loaded account than in a front-loaded account. For example, if an individual facing a 25 percent marginal income tax rate contributes $2,000 to a front-loaded account, he or she is really contributing $1,500 and $500 of government funds because of the tax deduction. When the funds are withdrawn, the government reclaims its share of the principal contribution, plus taxes on interest earned (table 3). In a back-loaded account, however, taxes are paid on the initial contribution and interest can be withdrawn tax-free. Note the distinction here. The value of the tax shelter per dollar saved is the same with either account. However, if the nominal contribution limits are identical, a determined saver can sock away more with a back-loaded account.

Updated January 2024

Austin, Lydia. 2016. “How Economists Eliminate Taxes on Your Retirement Income.” TaxVox. Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Bell, Elizabeth, Adam Carasso, and C. Eugene Steuerle. 2004. “Retirement Saving Incentives and Personal Saving.” Tax Notes. December 20.

Beshears, John, James J. Choi, David Laibson, and Brigitte C. Madrian. 2014. “Does Front-Loading Taxation Increase Savings? Evidence from Roth 401(k) Introductions.” NBER working paper 20738. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Burman, Leonard E., William G. Gale, and David Weiner. 2001. “The Taxation of Retirement Saving: Choosing between Front-Loaded and Back-Loaded Options.” National Tax Journal 54 (3): 689–702.