Workers, owners of capital, and households that consume a disproportionate amount of taxed items all bear the burden of federal excise taxes.

Excise taxes create a wedge between the price the final consumer pays and what the producer receives. An excise can raise the total price (inclusive of the excise tax) consumers pay, reduce the after-tax revenue available to compensate workers and investors, or both.

The burden of an excise can be separated into two pieces: (1) the reduction in real household income, which equals the gross revenue generated by the excise tax and (2) the increase in the price of the taxed good or service relative to the prices of other goods and services, which depends on the mix of consumption by each household. Importantly, the decline in real income is the same regardless of whether nominal incomes fall (holding the price level constant) or the price level rises (holding nominal incomes constant).

REDUCTION IN REAL INCOME

The reduction in real income is spread across wages, profits, and other returns to labor and capital, but excludes the normal return to savings that represents the reward for deferring consumption to a future year. The reduction in wages, in turn, reduces both individual income taxes and payroll taxes. Likewise, the reduction in profits reduces corporate income taxes and individual income taxes on the profits of pass-through business (like partnerships) and other returns to capital. These “excise tax offsets” amount to about 22 percent of excise tax revenues and are considered in distributional analyses.

CHANGE IN RELATIVE PRICES

An excise tax also increases the price of the taxed good or service relative to the prices of all other goods and services. While the price of the taxed item rises, the prices of all other items may either remain unchanged as the overall price level rises or fall slightly if the price level remains unchanged.

Either way, this change in relative prices burdens households that consume a larger-than-average share of the taxed item. However, households that consume a smaller-than-average share of the taxed item, or do not consume it at all, benefit from this change in relative prices.

TIMING OF THE TAX BURDEN

This still leaves open the timing of the tax burden—that is, whether the burden is assigned when income is earned or when it is consumed. Some distributional analyses follow the latter approach and distribute excise taxes in proportion to current levels of consumption. Alternative analyses assign the burden based on current income. Under the income-based approach, one can think of excise taxes as a reduction in purchasing power at the point income is earned. Of course, if all households fully consumed their income in each year, the two methods would yield identical results.

The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center distributes the burden of an excise tax when income is earned, taking into account the “offset” and the relative price effect. The US Department of the Treasury’s Office of Tax Analysis, as described in Cronin (1999), distributes excise taxes in the same manner. The Joint Committee on Taxation and the Congressional Budget Office, however, distribute the entire burden of excises in proportion to consumption of the taxed goods and services.

DISTRIBUTION OF FEDERAL EXCISE TAXES

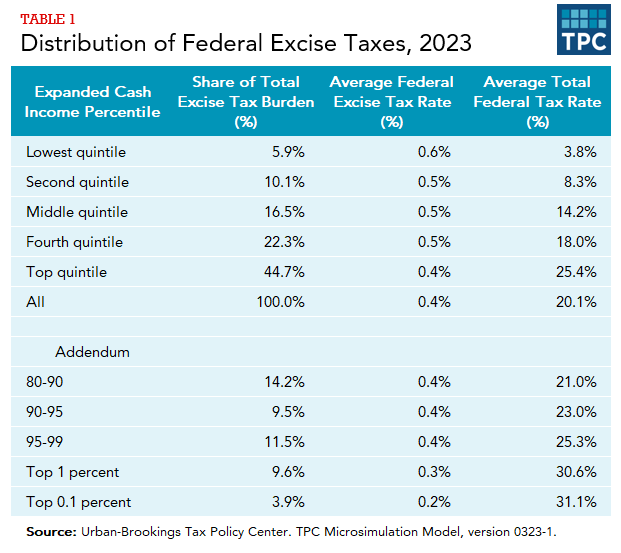

While the share of federal excise tax paid rises with income, federal excises are regressive. That is, the average federal excise tax rate (the excise tax burden as a percentage of pretax income) declines as income rises. The average excise tax rate falls from 0.6 percent in the bottom quintile to 0.4 in highest quintile, and to 0.3 percent of income in the top 1 percent (table 1). (Each quintile contains 20 percent of the population, ranked by income.)

Federal excise taxes also account for a larger share of the total federal tax burden (including individual and corporate income taxes, payroll taxes, the estate tax, and excise taxes) for lower-income groups than for higher-income groups. In the bottom two quintiles, excise taxes are the second-largest source of the total federal tax burden, behind payroll taxes. Those income groups have negative average income tax rates resulting from refundable income tax credits.

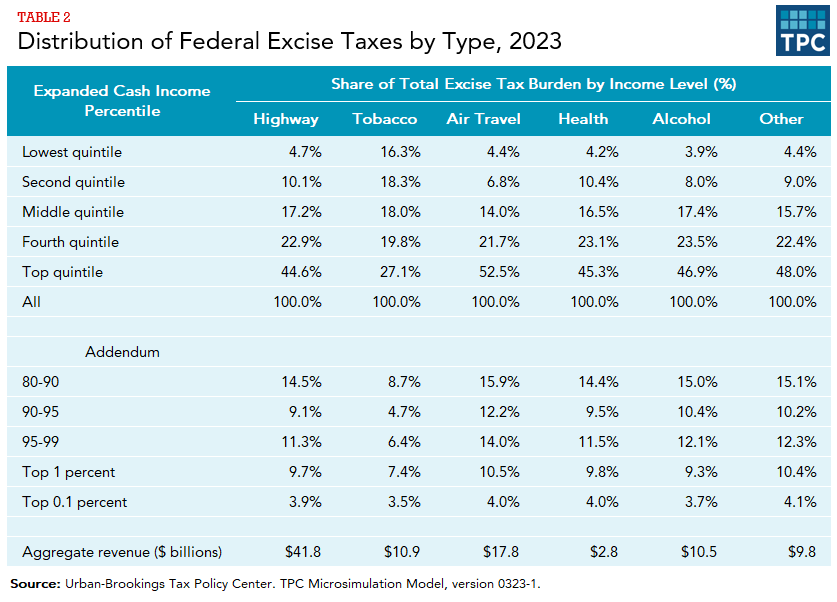

Federal excise tax revenues totaled $88 billion in fiscal year 2022, or 2 percent of total federal tax revenues. Five categories of excise taxes—highway, tobacco, air travel, health, and alcohol—account for 90 percent of total federal excise tax receipts.

The distributional burden varies somewhat across the different categories of excise taxes (table 2). The tobacco excise tax, for example, has the least varying share of taxes paid across income quintiles. The bottom quintile pays 16 percent of tobacco taxes, while the top quintile pays 27 percent of tobacco taxes (compared to over 45 percent of other excises). Tobacco taxes are the most regressive of the major federal excise taxes. The remaining categories differ only modestly from each other. Excise taxes on air travel are tilted relatively more towards higher-income households, with 53 percent paid by households in the top income quintile.

Updated January 2024

Congressional Budget Office. 2016. “The Distribution of Household Income and Federal Taxes, 2013.” Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office.

Cronin, Julie-Anne. 1999. “US Treasury Distributional Analysis Methodology.” OTA Paper 85. Washington, DC: US Department of the Treasury.

Joint Committee on Taxation. 1993. “Methodology and Issues in Measuring Changes in the Distribution of Tax Burdens.” JCS-7-93. Washington, DC: Joint Committee on Taxation.

Rosenberg, Joseph. 2015. “The Distributional Burden of Federal Excise Taxes.” Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Toder, Eric, Jim Nunns, and Joseph Rosenberg, 2011. “Methodology for Distributing a VAT.” Washington, DC: Pew Charitable Trusts and Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.