A revenue-neutral national retail sales tax would be more regressive than the income tax it replaces.

A national retail sales tax would create a wedge between the prices consumers pay and the amount sellers receive. Theory and evidence suggest that the tax would be passed along to consumers via higher prices.

Because lower-income households spend a greater share of their income than higher-income households do, the burden of a retail sales tax is regressive when measured as a share of current income: the tax burden as a share of income is highest for low-income households and falls sharply as household income rises. The burden of a sales tax is more proportional to income when measured as a share of income over a lifetime. Even by a lifetime income measure, however, the burden of a sales tax as a share of income is lower for high-income households than for other households: a sales tax (like any consumption tax) does not tax the returns (such as dividends and capital gains) from new capital investment and income from capital makes up a larger portion of the total income of high-income households.

In contrast, federal income taxes are progressive. The individual income tax is progressive thanks to refundable credits for lower-income households (average tax rates are negative for the two lowest income quintiles), the standard deduction (which exempts a minimum income from the tax), and a graduated rate structure (rates on ordinary income rise from 10 to 37 percent, with an additional 3.8 percent marginal tax on certain investment income of high-income households).

The President’s Advisory Panel (2005) concluded that replacing the income tax system with a national retail sales tax would heavily favor high-income households. A sales tax rate of 22 percent (the rate necessary to replace the revenue from the federal income tax at that time) would increase tax burdens on the lower 80 percent of the income distribution by approximately $250 billion a year (in 2006 dollars), if the sales tax were not modified to return some revenue to lower-income households.

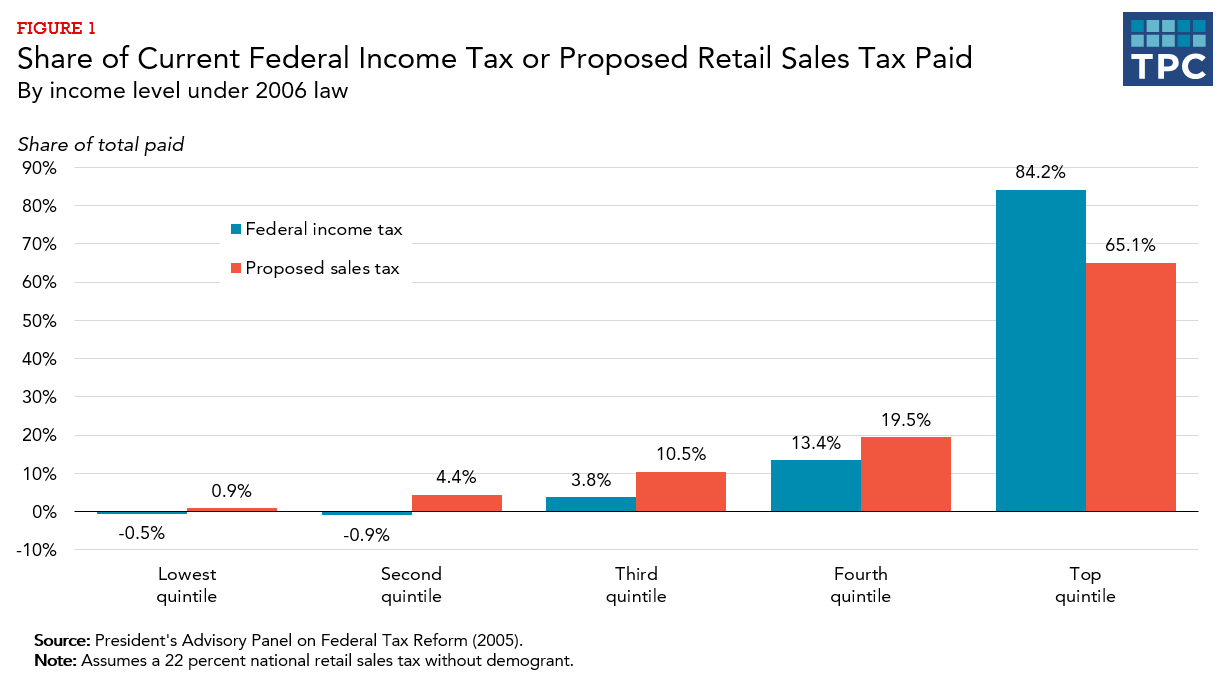

Put another way, the lower 80 percent of the income distribution would go from paying 15.8 percent of federal income taxes to paying 34.9 percent of federal retail sales taxes. Conversely, the top 20 percent of the income distribution would go from paying 84.2 percent of federal income taxes to 65.1 percent of federal retail sales taxes (figure 1).

The Advisory Panel also found that offsetting the regressivity by per capita rebates to disadvantaged households would require a 34 percent sales tax rate to sustain revenue.

Some claim that a properly modified national retail sales tax would be “pro-family.” Advocates usually point to the proposed demogrant—the per capita cash rebates—as proof of this assertion. On the other side of the ledger, though, families with children would likely be hurt by the elimination of both current deductions for health insurance, mortgage interest, and state and local income and property taxes (which finance schools and other government services) and by the elimination of various tax credits (the EITC, child care credits, education credits, and child tax credits). Consider, too, that at any given income level, families with children have higher consumption requirements than those without, so switching to a consumption tax would present an inherent disadvantage for families with kids.

Updated January 2024

President’s Advisory Panel on Federal Tax Reform. 2005. Simple, Fair, and Pro-Growth: Proposals to Fix America’s Tax System. Washington, DC: President’s Advisory Panel on Federal Tax Reform.