The charitable deduction subsidizes charitable giving by lowering the net cost to the donor. If the tax deduction spurs additional giving, charitable organizations can provide more services.

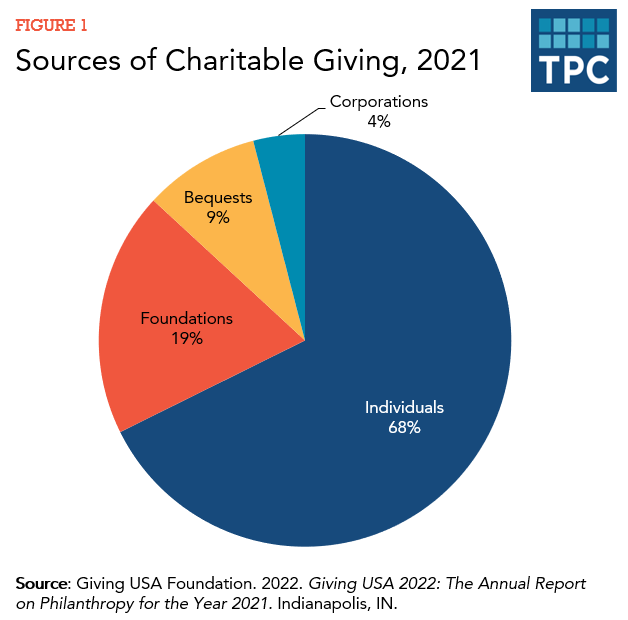

A charitable contribution is intended for the benefit of those supported by the charitable activity, whether through education, health care, or the like. Approximately two-thirds of charitable giving comes directly from individuals, with the balance coming from foundations, estates, and corporations (figure 1). According to Giving USA, total contributions totaled $484.85 billion in 2021, though there is some double counting, in the sense that this year’s grants by foundations derive from past contributions by individuals, corporations, and bequests.

While the main beneficiaries of the charitable gifts are those served by charities, the charitable deduction subsidizes donors by lowering their net cost of making the gift. Just how much the tax deductibility lowers the cost of giving depends on the donor’s marginal tax rate. For instance, a donor in the 24 percent tax bracket pays 24 cents less tax for every dollar donated. Higher-income individuals generally save more taxes by giving to charity than those with lower incomes for two reasons: they have higher marginal tax rates, and they are more likely to itemize deductions and take advantage of the tax savings.

The deductibility of contributions is usually justified as a subsidy for charitable activity, an appropriate adjustment to the tax base, or both. Many economists and lawyers argue that a taxpayer’s taxable income should be determined by income net of contributions, because a taxpayer with, say, $50,000 of income and $10,000 of contributions has no more ability to consume than someone with $40,000 of income and no contributions. Others see the $10,000 as a “consumption”-like choice made by the donor that does not warrant special tax treatment. With or without a deduction to the donor, the “income” value of the charitable gift is excluded from the taxable income of beneficiaries.

Donors may choose which charitable activities to support. Thus, because part of the cost of donations is borne by the government through reduced revenue, donors effectively have some say in which activities the government supports. The same situation exists in many other programs, such as tax credits for research and development, whereby businesses effectively which eligible research activities that the government supports.

Some donations fund activities that substitute for those the government might otherwise undertake. Other donations complement government activities, and still others support an adversarial relationship with government. Nonprofits, for instance, may seek government funding for an activity, or its members may engage in debates with government officials, though various rules limit outright lobbying. Many believe these types of charitable activity make democracies healthier, even when particular chartable efforts have little impact.

Although the tax deduction likely induces additional giving, estimates of the size of this effect vary. Indeed, there is considerable debate over whether the increase in giving exceeds the loss of government revenue, though valuing the deduction on that basis alone treats charitable contributions and government spending simply as substitutes.

Updated January 2024

Boris, Elizabeth T., and C. Eugene Steuerle, eds. 2016. Nonprofits and Government: Collaboration and Conflict, 3rd ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Colinvaux, Roger, and Harvey P. Dale. 2015. “The Charitable Contributions Deduction: Federal Tax Rules.” Tax Lawyer 68 (2): 332–66

Giving USA Foundation. 2022. Giving USA 2022: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2021. Indianapolis, IN.

Randolph, William C. 2005. “Charitable Deductions.” In NTA Encyclopedia of Taxation and Tax Policy, 2nd ed., edited by Joseph J. Cordes, Robert D. Ebel, and Jane G. Gravelle, 51–53. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.