Balanced budget requirements (BBRs) are constitutional or statutory rules that generally prohibit states from spending more than they collect in revenue in a fiscal year. However, these state rules vary in stringency and design. Research finds that stricter BBRs can produce “tighter” state fiscal outcomes such as reduced spending and smaller deficits, but they also can force states to quickly cut services or raise taxes in the middle of an economic downturn.

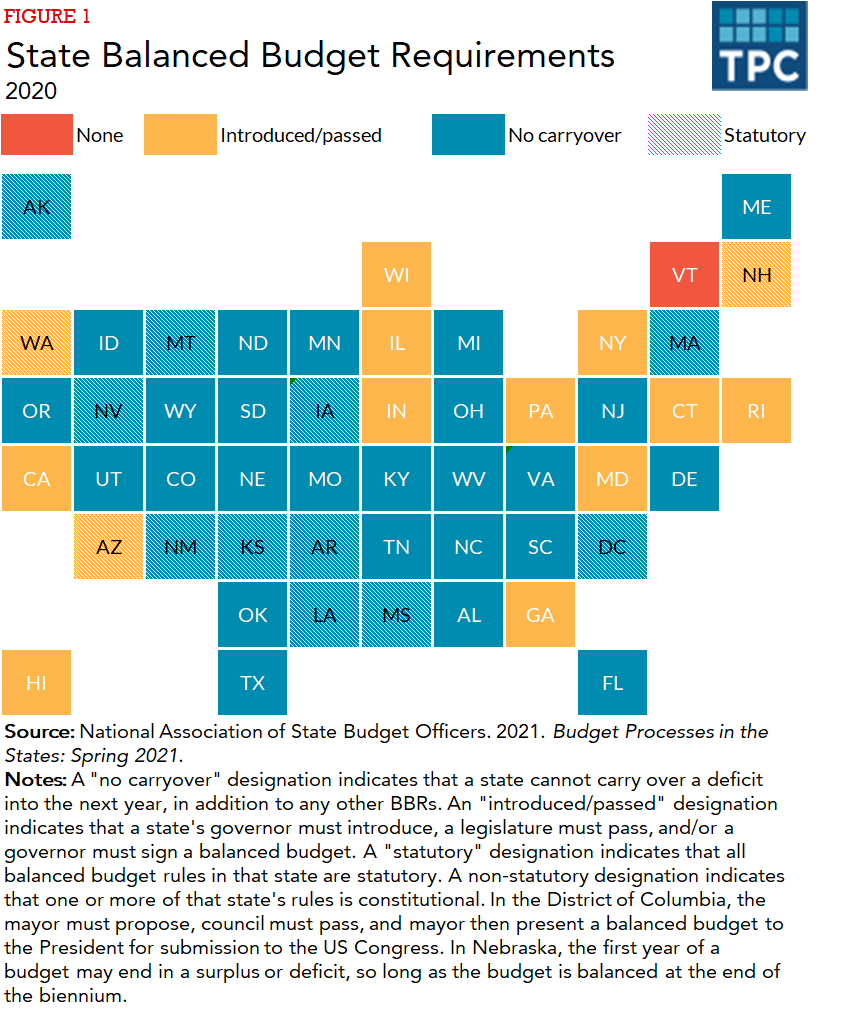

According to the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO), all states except for Vermont have some stipulations to balance their operating budgets—but prohibitions and enforcements vary. For example, although Arizona requires the governor to propose a balanced budget, it does not require the legislature to pass one. By comparison, Texas and West Virginia require the legislature to pass a balanced budget, but they do not require the governor’s initial proposal to be balanced. In California, the governor must propose, the legislature must pass, and the governor must ultimately sign a balanced budget.

In 2021, 45 states required the governor to submit a balanced budget to the legislature; 44 states required the legislature to pass a balanced budget; 41 states required the governor to ultimately sign a balanced budget; and 35 states required the budget to be balanced at year-end (that is, the state cannot “carry over” a deficit). Overall, 29 states and the District of Columbia imposed all four requirements on their budget process. Still, BBRs typically only apply to states’ operating budgets, meaning that capital and pension funds are usually exempt from these limitations.

While researchers have debated how to best classify the relative strength of a state’s BBR, recent research suggests a BBR is more binding (i.e., stricter) if it meets at least one of the following requirements:

- the governor must sign a balanced budget;

- the state is prohibited from carrying over a deficit into the following fiscal year or biennium; or

- the legislature must pass a balanced budget accompanied by either limits on supplementary appropriations or within fiscal-year controls to avoid a deficit.

But there are other ways to address or prevent deficits. In Louisiana and Wisconsin, any deficit must be addressed in the next year’s budget. In Connecticut, the comptroller must transfer funds from the Budget Reserve Fund to extinguish any year-end deficit; if balances in the Fund are inadequate to do so, the governor must extinguish the deficit in their budget proposal for the next year.

BBRs can be either constitutional or statutory. While constitutional or statutory designations do not necessarily determine whether a rule is strong or weak, constitutional requirements can be more difficult to override, and may require a legislative supermajority or vote of the people to amend.

Circumventing Balanced Budget Requirements

Under some circumstances, state policymakers can circumvent their BBRs. These rules typically apply to a narrowly defined share of total state spending, and government fund accounting practices can provide opportunities to shift obligations between funds or years.

For example, because BBRs are applied on a cash rather than accrual basis, states can push a payroll or state aid payment from the last month of the current fiscal year into the first month of the next. This allows states to meet the legal requirement to balance their budgets while leaving actual resources and obligations out of balance.

These actions only produce one-time savings, however, as the state simply transfers its obligation to the following fiscal year. If a shortfall results from sudden changes in economic conditions, this flexibility can allow a state time to recover economically and meet its fiscal obligations. However, it can also lead to ongoing reallocation of expenses to the next budget year.

Impacts

Strong antideficit provisions, such as those in BBRs, are associated with:

- reduced spending

- smaller deficits

- more rapid spending adjustments during recessions

- less debt

- lower borrowing costs

- higher surpluses, which states can then deposit into a budget stabilization fund to smooth over gaps in spending at later dates.

Fiscal and budgetary institutions like BBRs, particularly when enforced strongly, influence both the size and composition of states' responses to fiscal deficits.

Recent research shows that states with relatively strong BBRs cut their budgets more in response to deficits than states with weaker rules. This was true for the two decades preceding the 2008 recession and it became even more pronounced between 2008 and 2015 (Rueben, Randall, and Boddupalli 2018). Additionally, in more recent years, states with strong balanced budget rules bridged less of their gap with revenue increases than in years prior, leaning more on spending cuts or possibly reserve funds to bridge gaps.

However, strict BBRs can also increase states’ fiscal and economic volatility, since they force a state to enact spending cuts or revenue increases when a state’s economy is already contracting (Bayoumi and Eichengreen 1995; Levinson 1998, 2007). These actions exacerbate, rather than counter, the effects of an economic contraction. During and following the Great Recession, for example, states with strong BBRs cut their budgets and raised revenues precisely when the economy and residents would benefit from states spending more and easing taxes.

Updated January 2024

Randall, Megan, and Kim Rueben. 2017. “Sustainable Budgeting in the States: Evidence on State Budget Institutions and Practices.” Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Rueben, Kim, Megan Randall, and Aravind Boddupalli. 2018. “Budget Processes and the Great Recession: How State Fiscal Institutions Shape Tax and Spending Decisions.” Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Levinson, Arik. 2007. “Budget Rules and State Business Cycles: A Comment.” Public Finance Review 35 (4): 545–549. https://doi.org/10.1177/1091142107301758.