Updated on August 10, 2018.

The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center’s business tax model is used to estimate the effects of tax proposals on federal revenue, incentives to invest, choices related to the source of financing (i.e., debt vs. equity) and form of business organization (e.g., corporate vs. pass-through), and tax burdens across firms and industries. This paper details the data sources and mechanics of that model.

Framework for Modeling Business Activity in the US

The Tax Policy Center (TPC) regularly estimates the revenue, distributional, and economic effects of tax policy changes. Most of TPC’s estimates are produced with its large-scale microsimulation model. That model is similar to those used by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), and the Treasury’s Office of Tax Analysis (OTA), and is based on a large publicly-available dataset of federal individual income tax returns. Most proposals related to the taxation of corporations and other business tax provisions cannot be estimated using the individual microsimulation model and are currently produced using a series of “off-model” methods.1

Ideally, we would construct a business model analogous to TPC’s individual microsimulation model. However, no similar publicly available firm-level micro datafile exists. To construct the model, we combine aggregated, but detailed, tabulations published by the Statistics of Income Division (SOI) of the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and other government agencies to construct a core data file for a base year, currently 2013. The result is a database of “synthetic firms,” which are assigned the average characteristics for a given firm type defined across several dimensions in order to capture the heterogeneity across the business sector. Those dimensions include the a) legal form of organization, b) industry group, and c) profit/loss status.

Constructing Representative Firms

Legal form of organization

Most large publicly-traded businesses operate as traditional C corporations (named after the relevant subchapter of the Internal Revenue Code). C corporations pay the corporate income tax, an entity-level tax with graduated rates ranging from 15 to 35 percent. Profits in C corporations may be subject to a second layer of tax at the individual level as dividends when distributed or as capital gains when shares are sold.

However, most businesses in the US operate as pass-through entities. Pass-throughs are not subject to an entity-level tax, but rather their net income is allocated and reported on their owners’ individual income tax returns. Pass-throughs, however, generally are subject to the same tax rules for determining taxable income as C corporations. There are three main types of pass-throughs: sole proprietorships, partnerships, and S corporations.

Sole proprietorships have a single owner and do not file a separate tax return. Business receipts and deductions are reported and net income calculated on Schedule C of the owner’s individual tax return. Not all Schedule C filers are engaged in business activity, but rather are simply reporting miscellaneous personal income.

Partnerships file an entity-level tax return (Form 1065), but profits are allocated to owners who report their share of net income on Schedule E of their individual tax returns. Partnerships are generally classified as either general partnerships, limited partnerships, or limited liability companies (LLCs). The number of LLCs has grown dramatically and they now account for 70 percent of all partnership returns filed.

Corporations that elect S corporate status file a corporate tax return (Form 1120S), but profits flow through to shareholders and are reported on Schedule E of their individual tax return. S corporations can have only one class of stock, cannot have more than 100 shareholders, and those shareholders must be US citizens or resident individuals (although certain estates, trusts, and tax-exempt organizations are also allowed). S corporation owners are required to pay themselves “reasonable compensation,” which is reported as regular wage and salary income.

In addition, there are several special types of C corporations that function as pass-throughs. Regulated investment companies (RICs) and real estate investment trusts (REITs) are generally not subject to an entity level tax provided they meet requirements about the forms of income they receive and the amount of income they distribute. Those entities file specialized tax returns and can be separated out from other C corporations in published IRS data.

Profit Status

Roughly one-third of businesses do not report positive net income in any given year. C corporations with losses can “carry-back” their losses to the previous two tax years or “carry-forward” their losses for up to 20 years to offset positive income. Losses in pass-throughs can be used to offset other forms of income reported by their owners, although limitations apply for passive investors who are not “material participants” in the business.

Industry

Firms are classified into industries in published federal statistics according to the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). There are 19 2-digit sectors: Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting; Mining (including oil and gas extraction); Utilities; Construction; Manufacturing; Wholesale trade; Retail trade; Transportation and warehousing; Information; Finance and insurance; Real estate and rental and leasing; Professional, scientific, and technical services; Management of companies and enterprises; Administrative and support and waste management and remediation services; Educational services; Health care and social assistance; Arts, entertainment, and recreation; Accommodation and food services; and Other services (except public administration).

SOI publishes data at the more detailed major industry level, which generally corresponds to 3-digit NAICS codes. Industry coverage varies slightly across SOI product, but the major industry level generally contains between 80 and 120 categories. In order to maintain as much heterogeneity as possible, we preserve all the detail contained in the SOI products even though some observations need to be combined to compare at a more aggregated level (table A1).

Creation of Base Year Sample

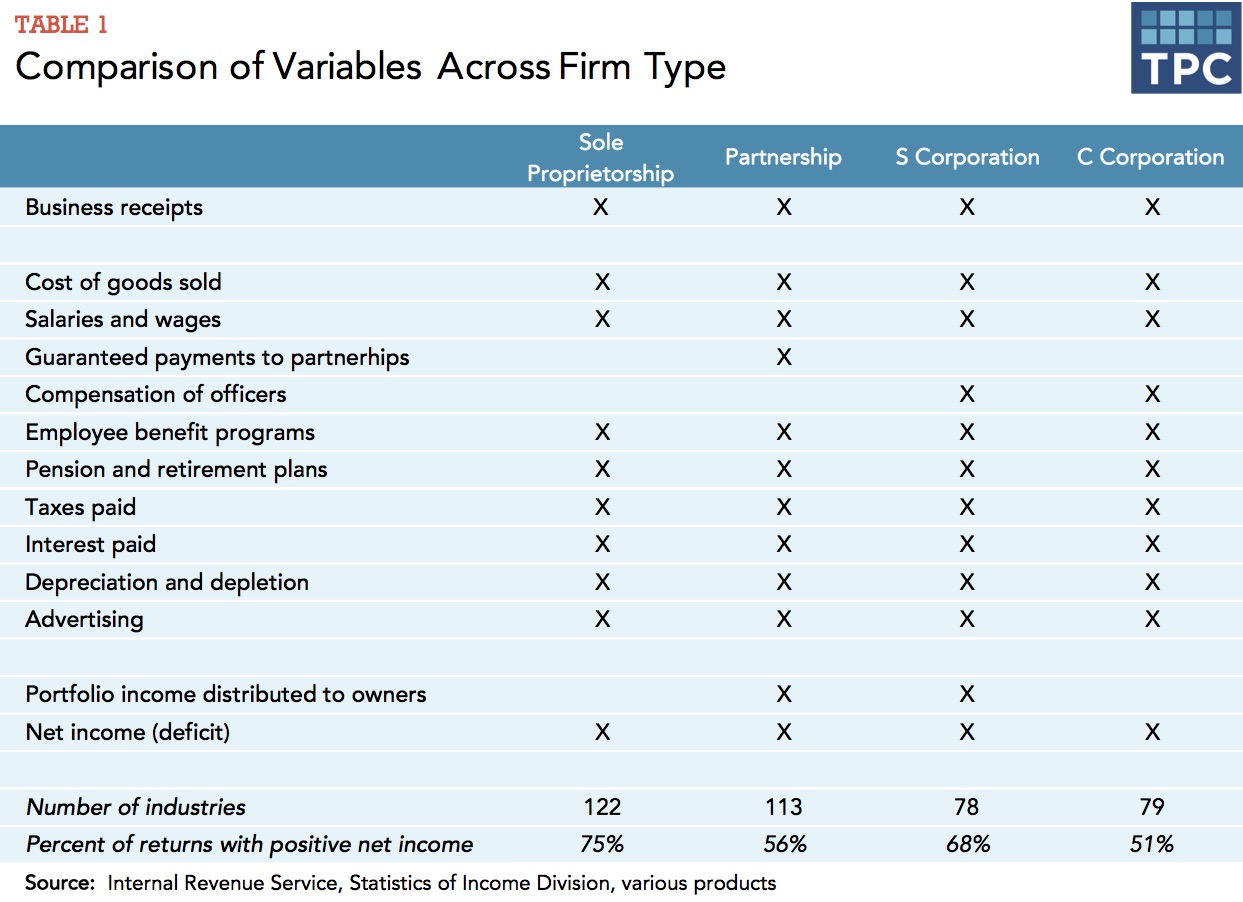

The business tax model contains balance sheet, income, and deductions items reported on tax returns for roughly 800 synthetic firms across all the entity types, industries, and profit status (table 1). This section details the various sources that are used to construct the model’s core datafile.

C Corporations

Data for C corporations come from several sources of published data from SOI. Tables 12 and 13 of the Corporate Complete Report provides balance sheet and income statement variables across 79 major industry groups, separately for all returns and for just those returns with positive net income. In 2013, nearly 820,000 C corporation returns with positive net income were filed, reporting average business receipts of $20 million and average net income of $1.8 million (table 2). The average corporate income tax after credits due was roughly $360,000. An almost equal number of returns reported a net loss, with average business receipts of $4.5 million and an average net loss of $400,000.

S Corporations

The main source of data are the S corporate tables of SOI’s Corporation Complete Report, which covers all corporations that file a Form 1120S. Those tables report balance sheet and income statement variables across 78 major industry groups, separately for all returns and for just those returns with positive net income. In 2013, more than 2.9 million S corporation returns with positive net income were filed, reporting average business receipts of nearly $2 million and average net income of $154,000 (table 3). In addition, 1.3 million S corporation returns reported a net loss, with average business receipts of $731,000 and an average net loss of $51,000.

Partnerships

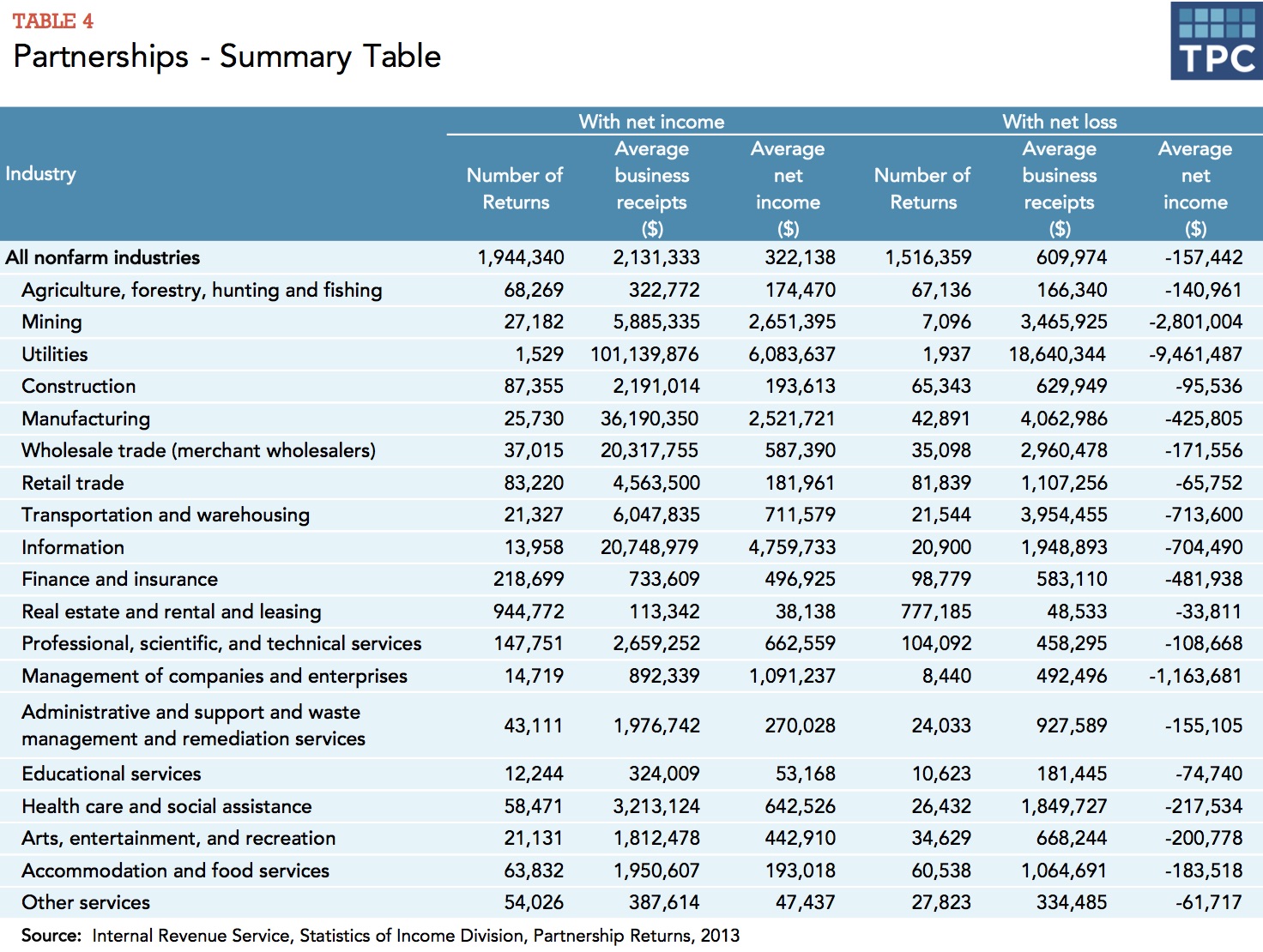

Data for partnerships come from Table 1 and Table 2 of SOI’s Partnership program. That sample covers all partnerships that file a Form 1065 and reports balance sheet and income statement items across 113 major industries, separately for all businesses and just those reporting positive net income. In 2013, more than 1.9 million partnership returns with positive net income were filed, reporting average business receipts of $2.1 million and average net income of $322,000 (table 4). In addition, 1.5 million partnership returns were filed reporting a net loss, with average business receipts of $610,000 and an average net loss of $157,000.

Sole Proprietorships

The main source of sole proprietorship data is Table 2 of SOI’s Nonfarm Sole Proprietorship study. That study covers all sole proprietorships that file a Schedule C with their federal return and reports business receipts, deductions, and net income across 122 industry groups, separately for businesses with net income and net losses. In 2013, nearly 18 million returns reported positive net income on Schedule C, with average business receipts of about $63,500 and average net income of $19,900 (table 5). Another 6.1 million returns reported a net loss, with average business receipts of $33,000 and an average net loss of $9,000.

Extrapolation and Calibration

The 2013 base year file is extrapolated for tax years 2014 to 2027 using a two-step process. First, average income and deduction items for each representative firm are grown based on the economic forecast published by the CBO. The time pattern of depreciation deductions is estimated from TPC’s off-model depreciation calculator. The number of returns and the fraction of returns with net loss are then adjusted to his calibration targets (table 6). For C corporations, tax year liability is calibrated to match CBO’s projected amount of fiscal year revenue. For pass-throughs, the amount of net income attributable to individuals is calibrated to match the amount of net income from TPC microsimulation tax model.

Framework for Measuring Investment Incentives

User Cost of Capital

Similar to Rosenberg and Marron (2015), we use the standard framework for measuring the effect of taxes on investment incentives the incentive effects of capital income taxation developed by King and Fullerton (1984), Auerbach (1987), Gravelle (1994), and Mackie (2002), and similar to the methodologies used by the Congressional Budget Office (2014) and the US Treasury Department’s Office of Tax Analysis (2014). The user cost of capital is the minimum pre-tax rate of return (gross of depreciation) that investors require for undertaking an investment project. That is, it is the return necessary to exactly compensate for taxes, depreciation, and investors’ opportunity cost.

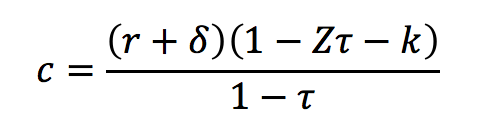

The user cost of capital can be expressed as:

where r is the firm’s real discount rate, δ is the rate of economic depreciation, Z is the present discounted value of tax depreciation allowances, τ is the firm’s income tax rate, and k is the rate of any investment tax credit.

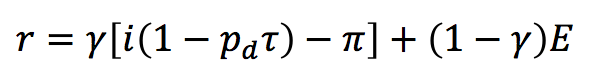

Firms finance new investments with a mix of debt and equity. The firm’s real discount rate is the weighted average cost of these two financing sources:

where γ is the fraction of investment financed by debt, i is the nominal interest rate paid on that debt, pd measures the fraction of the present value of interest deductions, π is the inflation rate, and E is the required real rate of return on equity. The effective cost of nominal interest expenses is reduced by the factor (1 - pd τ) to reflect the extent to which interest deductions are deductible by the firm.

Owner-Occupied Housing

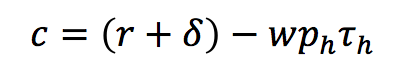

Owner-occupied housing represents a significant fraction of the overall capital stock and the (imputed) income it generates is not subject to tax. Additionally, local property taxes may not be fully deductible either because the owner does not elect to itemize deductions or the itemized deduction is limited. Therefore, the user cost for investments in owner-occupied housing is expressed as:

where w is property tax rate, ph is the fraction of property taxes deducted, and th is the tax rate that applies to the deduction.

Marginal Effective Tax Rates

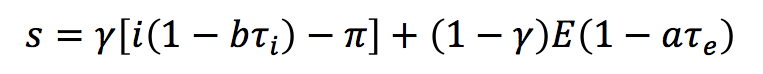

Taxes also affect the return ultimately received by savers. The saver’s after-tax return(s) is expressed:

where τi is the tax rate on interest income and τe is the tax rate on equity income. For corporations, τe represents a weighted average tax rate that applies to dividends and capital gains; since pass-through businesses are not subject to an investor-level tax on distributions, the tax rate on equity is equal to zero in the noncorporate sector. Since not all income earned by savers is subject to tax (e.g., income earned in tax-preferred accounts or by tax-exempt investors), the parameters a and b represent the fraction of equity and interest returns, respectively, that are subject to tax.

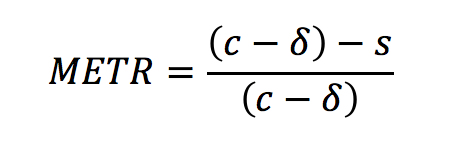

The marginal effective tax rate (METR) is a summary measure of the total tax burden at both the firm and investor levels. It equals the difference between the real pre-tax rate of return that a hypothetical project would generate (net of economic depreciation) and the real after-tax rate of return that savers would receive, measured as a percentage of the real pre-tax rate of return:

Data Sources and Model Assumptions

Data

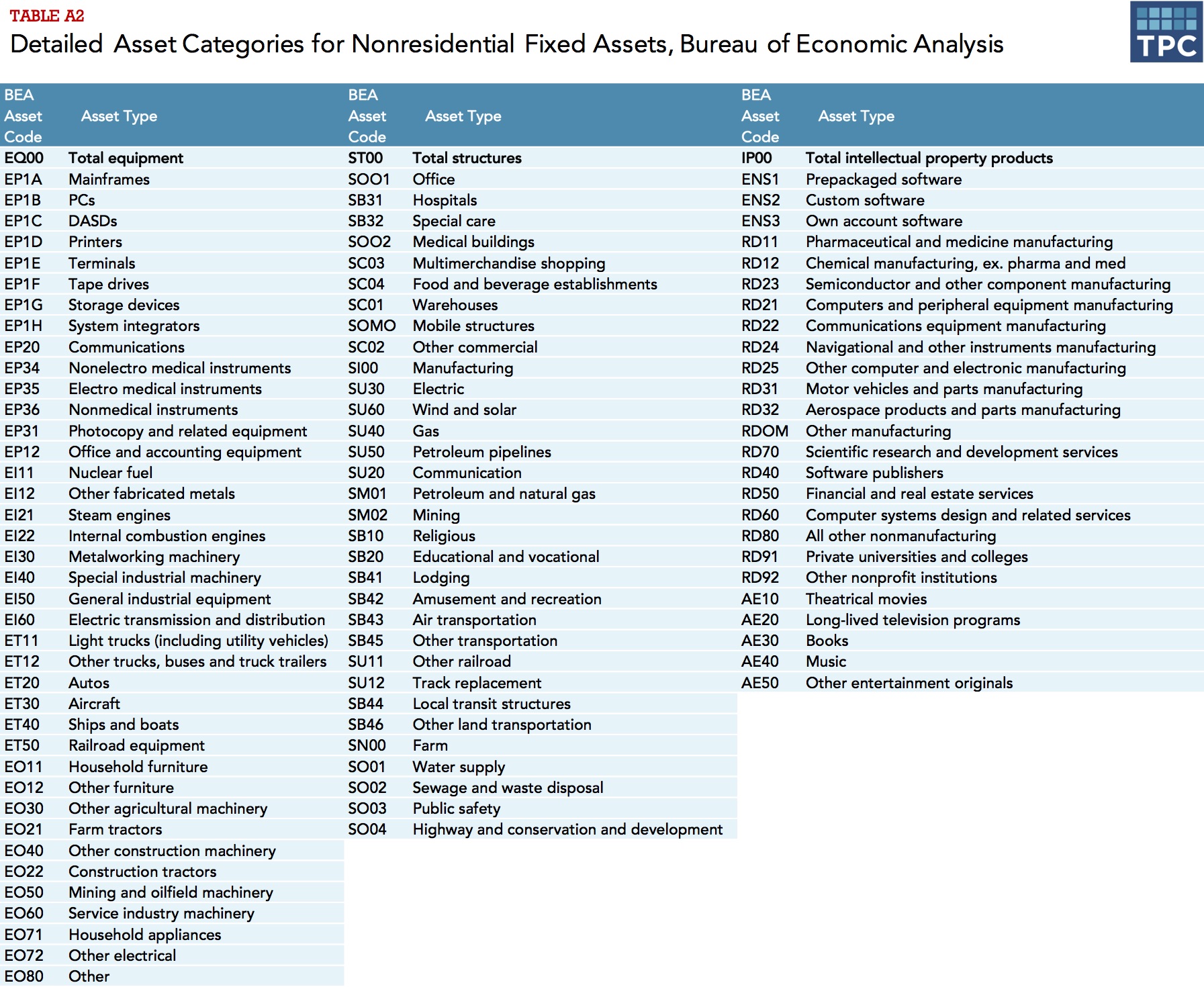

Bureau of Economic Analysis. The BEA’s fixed asset accounts include data on a) net stocks, b) investment, and c) rates of economic depreciation of the private nonresidential capital stock disaggregated into 62 detailed industry groups and 92 asset types (appendix table A2). BEA’s 92 asset types are classified into 3 main categories: equipment, structures, and intellectual property products (including software, research and development, and entertainment and artistic originals). The BEA also provides similar (but less detailed) data on the residential capital stock and inventories.

IRS, Statistics of Income (SOI). SOI data are used to assign the capital stock by industry and asset type into entity type (C corporation, S corporation, partnership, sole proprietor) and to estimate debt-equity financing ratios.

Modeling and Economic Assumptions

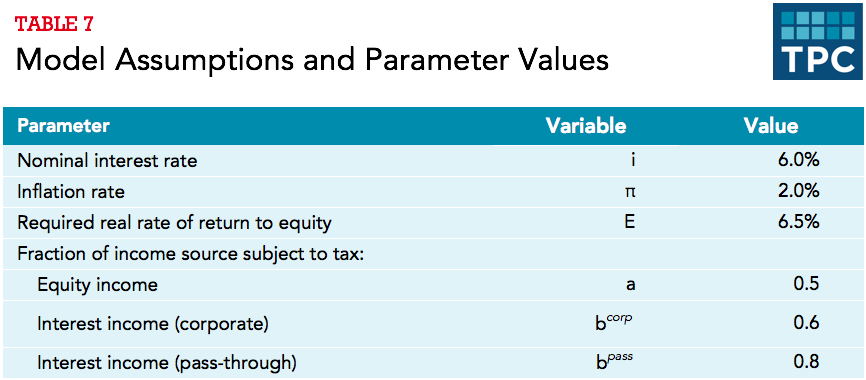

The calculations presented here abstract from risk and assume all firms face the same nominal interest rate and that after-tax returns to equity are equalized across firms and investment projects. Parameter values are shown in table 7.

1. More detail on TPC’s microsimulation tax model and current methodology for “off-model” estimates is available at: http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/resources/tax-model-resources.