The Build Back Better proposal for a 1 percent excise tax on corporate share buybacks would reduce their tax advantage relative to dividend distributions. Equivalent to a corporate tax rate increase of 0.8 percent on earnings distributed as share repurchases, the new tax would generate about $124 billion over 10 years and could induce higher corporate dividend payouts.

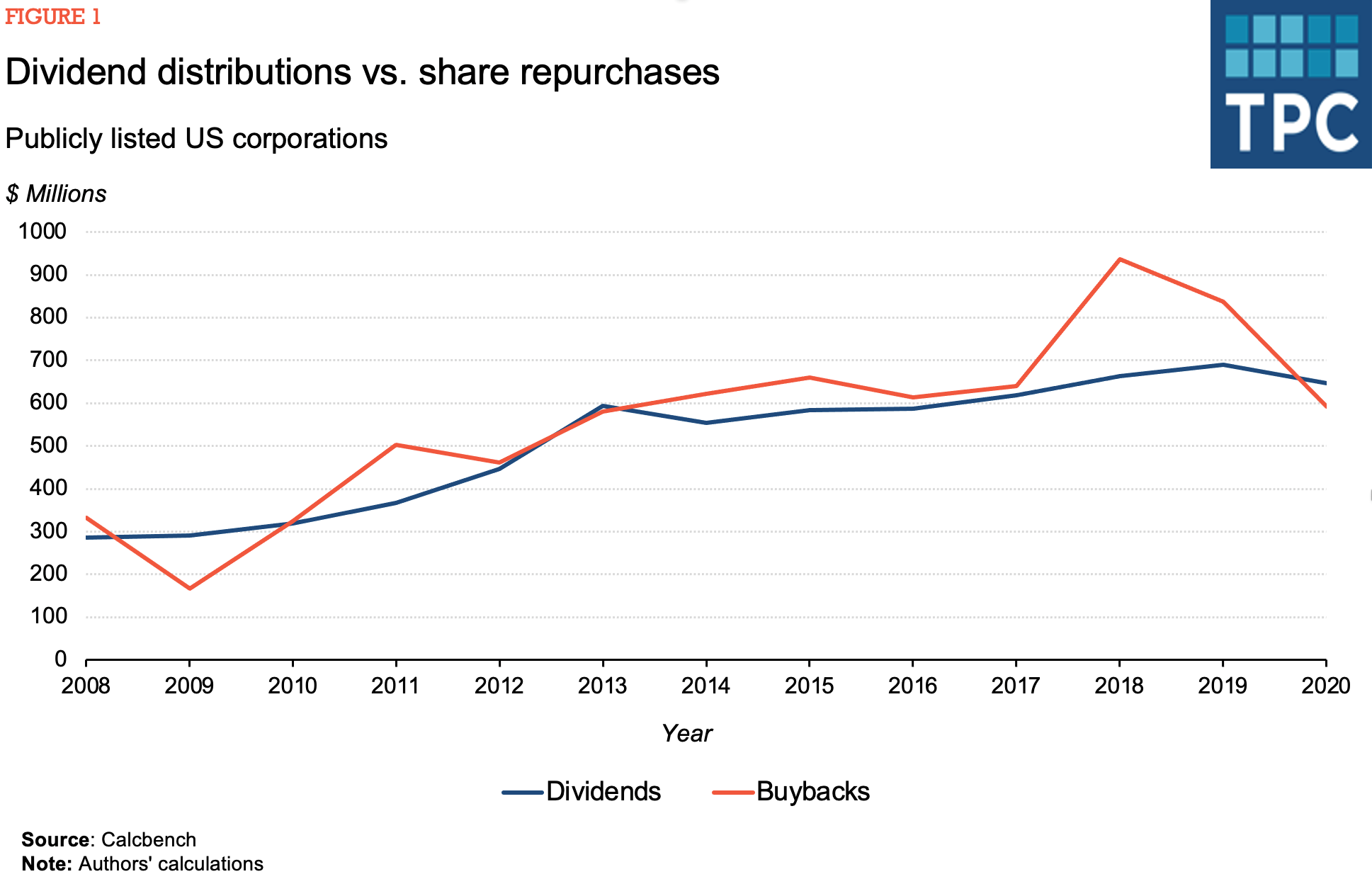

Share repurchases have been increasing in popularity since the Securities and Exchange Commission eased Rule 10b-18 in the early 1980s. Buyback volume has exceeded dividends in most years since 1997. And repatriation of offshore earnings triggered by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act led to a surge in buybacks in 2018 and 2019.

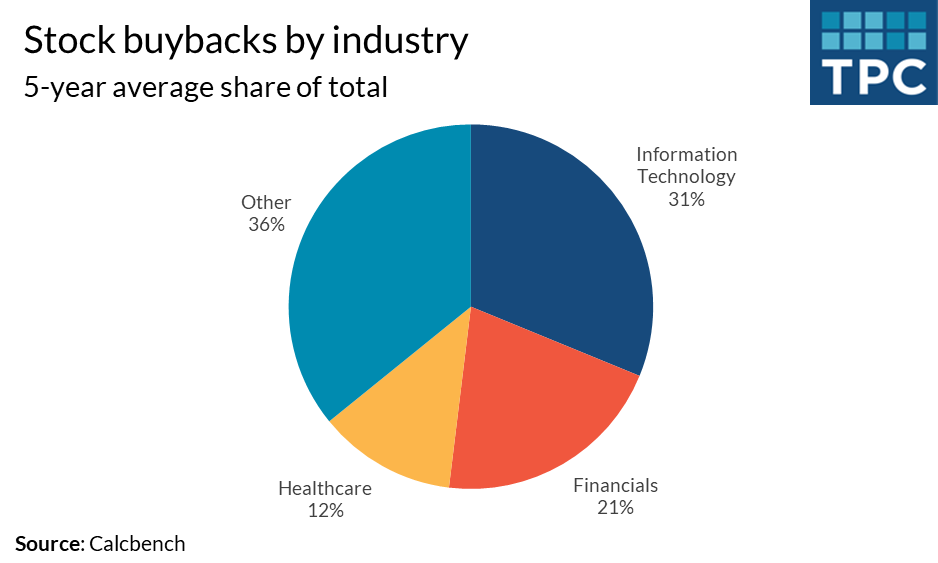

The industry with the largest share of buybacks, accounting for almost one third of the total, is information technology, which includes both electronics manufacturing and information services. Financials and health care were the next-largest sectors, with 21 percent and 12 percent of total buybacks, respectively.

The ongoing surge in corporate share buybacks has led to policy concerns about their use to avoid investor-level tax on corporate earnings as well as other non-tax costs. Some commentators argue that corporations should not distribute profits but reinvest them to raise productivity, wages, and economic growth. Nonetheless, it is efficient for corporations with relatively poor investment opportunities to distribute the income to shareholders, who can invest the proceeds in companies with better prospects.

Corporations can distribute earnings to shareholders as either dividends or share repurchases. Repurchases face a lower tax burden than dividends because they allow for greater deferral of capital gains. While dividends go to all shareholders, who are taxable on their full amount, share repurchases distribute earnings only to investors who sell their shares, who then pay capital gains tax on any profits from the sale. With a repurchase, other shareholders can avoid near-term taxation by simply not tendering their shares.

Thus, buybacks target distributions to shareholders who are less tax-sensitive. These include tax-exempt organizations, such as pension funds, that account for about 40 percent of US share ownership, as well as lower-income investors who face a zero capital gains tax rate. Foreign shareholders, who own more than a third of US corporate equity, face no US tax on capital gains, though they may be taxed by their country of residence.

Dividend distributions respond positively to increases in the relative taxation of capital gains. Based on an academic study, TPC estimates that a 1 percent tax rate on share repurchases could induce a roughly 1.5 percent increase in corporate dividend payouts.

Buybacks also have a variety of non-tax costs and benefits. They increase corporate leverage by reducing shareholder equity (and assets) while leaving liabilities unchanged. Firms may amplify this effect by borrowing to buy back shares, or indirectly by financing new investment with debt while distributing cash. Higher leverage can lead to financial fragility in economic downturns.

Buybacks offer corporate managers a more flexible way to distribute earnings than dividends. Since markets react negatively to dividend cuts, managers are careful not to increase dividends unless the new payout level can be sustained. Buybacks, however, can be implemented opportunistically.

Because buybacks tend to raise share prices, at least temporarily, corporate insiders can manipulate them to their own advantage. Repurchase demand drives up prices, and fewer outstanding shares raises earnings per share. This benefits shareholders who retain their shares, including corporate insiders who receive stock-based compensation. Reducing shares may help corporations hit their earnings-per-share targets. And higher share prices may encourage corporate boards to raise executive compensation.

Though US boards must authorize buyback programs in advance, corporations do not have to disclose actual repurchases until the end of the quarter in which they are made. That gives ordinary shareholders less information about this market-moving activity than corporate insiders.

Both buybacks and dividends can lead to a permanent rise in share value, if investors value a dollar outside the firm more than a dollar inside the firm. Corporate managers claim that share buybacks can signal to the market that shares are undervalued. However, share repurchases tend to follow market booms and busts, and studies find little significant long-term effect of share buybacks on share values.

Since share buybacks help avoid investor-level taxation, the buyback tax is a reasonable way to reduce their tax advantage. It raises significant revenue and could trigger an increase in dividend payouts. Insider trading concerns are better addressed by financial regulation: For example, some countries require shareholder pre-approval, prohibit insider participation and debt financing, and require same-day disclosure of share repurchases.