How fast will the US economy grow? When mainstream forecasters consult their crystal balls, they typically see real economic growth around 2 percent annually over the next decade. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and midpoint estimates of Federal Reserve officials and private forecasters cluster in that neighborhood.

When President Trump looks in his glowing orb, he sees a happier answer: 3 percent.

That percentage point difference is a big deal. Office of Management and Budget director Mick Mulvaney recently estimated the extra growth could add $16 trillion in economic activity over the next decade and almost $3 trillion in federal revenues.

But could our economy really grow that fast? Maybe, but we’d need to be both lucky and good. We’ve grown that fast before. But it’s harder now because of slower population growth and an aging workforce. And there are signs that productivity growth has slowed in recent years.

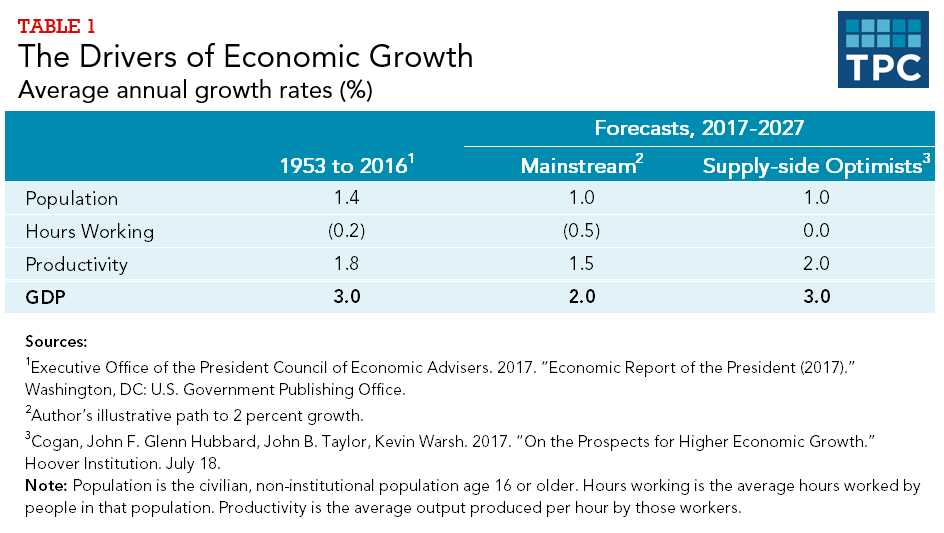

To illustrate the challenge, I’ve divvied up past and projected economic growth (measured as the annual growth rate in real gross domestic product) into three components: the growth rates of population, average working hours, and productivity.

The link between population and growth is simple: more people means more workers generating output and more consumers buying it. Increased working hours have a similar effect: more hours mean more output and larger incomes. Hours go up when more people enter the labor force, when more workers find jobs, and when folks with jobs work more.

Productivity measures how much a worker produces in an hour. Productivity depends on worker skills, the amount and quality of capital they use, managerial and organizational capability, technology, regulatory policy, and other factors.

As the first column illustrates, the US economy averaged 3 percent annual growth over more than six decades. Healthy growth in population and productivity offset a slight decline in average hours. Of course, that six-decade average includes many ups and downs. The Great Recession and its aftermath dragged growth down to only 1.4 percent over the past decade. In the half century before, the United States grew faster than 3 percent.

Mainstream forecasters like the CBO and the Federal Reserve expect slower future growth along all three dimensions. People are having fewer children, and more adults are moving beyond their child-rearing years, so population growth has slowed. Our workforce is aging. Baby boomers are cutting back hours and retiring, and younger workers aren’t fully replacing them, so average working hours will decline. Productivity growth has slowed sharply in recent years, for reasons that are not completely clear. Productivity is notoriously difficult to forecast, but recent weakness has inspired many forecasters to expect only moderate growth in the years to come.

Proponents of President Trump’s economic agenda offer a rosier view. Four prominent Republican economic advisers—John F. Cogan, Glenn Hubbard, John B. Taylor, and Kevin Warsh—recently argued that policy, not just demographic forces, has brought down recent growth. They claim supply-side policy reforms—cutting tax rates, trimming regulation, and reducing unproductive spending—can bring it back up. They argue that encouraging investment, reinvigorating productivity growth, and drawing enough people into the labor force to offset the demographic drag would generate persistent 3 percent growth.

Many analysts doubt such supply-side efforts can get us to 3 percent growth (e.g., here, here, here, and here). Encouraging investment and bringing more people into the labor force could certainly help, but finding a full percentage point of extra growth from supply-side reforms seems like a stretch. Especially if you plan to do it without boosting population growth.

The most direct supply-side policy would be expanding immigration, especially among working-age adults (reducing our exceptional rates of incarceration could also boost the noninstitutional population). But the Trump administration’s antipathy to immigration, and that of some Republicans in Congress, pushes the other way. Cutting legal immigration in half over the next decade could easily take 0.2 percentage points off future growth (see this nifty interactive tool from ProPublica and Moody’s Analytics). Three percent growth would then be even more of a stretch.

Another group of economists believes that demand-side policies—higher spending and supportive monetary policy—could lift growth above mainstream forecasts.

One trio of economists took a critical look at past efforts to forecast potential GDP growth, a key driver of long-run growth forecasts. They conclude that forecasters, including those at the Federal Reserve and the CBO, have overreacted to temporary economic shocks, overstating potential growth when times are good and understating it when times are bad. We’ve recently had bad times, so forecasters might be underestimating potential GDP almost 10 percent. If so, policies that boost demand could push up growth substantially in coming years. (For a related argument, see here.)

So where does that leave us?

Well, every crystal ball (and glowing orb) is cloudy. We should all be humble about our ability to forecast the economy over the next decade. Scarred by the Great Recession and its aftermath, forecasters may be inadvertently lowballing potential growth. Good luck and good supply- and demand-side policies might deliver more robust growth than they anticipate. But those scars remind us we can’t always count on good policy, and luck sometimes runs bad.

We can hope that luck and good policy lift growth to 3 percent. But it’s prudent to plan for 2 percent, and pray we don’t fall to 1 percent.