In March 2020, Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey signed a $11.8 billion budget that was $500 million lower than what he had proposed just weeks earlier—before the outbreak of COVID-19. And Ducey predicted “many tough decisions ahead of us as we better understand the full impact of this crisis on our citizens and on our economy.”

One year later the governor signed a budget that increased spending by $1 billion and cut taxes by nearly $2 billion annually. So much for those tough decisions.

While Arizona’s tax cut is particularly large—in part because of a fight over a tax-related ballot measure—by my count roughly half the states have passed some sort of major tax cut this year, and that’s not even counting states that reduced taxes by conforming with federal tax laws, such as adopting the feds’ $10,200 exemption for unemployment income.

The apparent good fiscal news in many state capitols has led some on Capitol Hill to propose taking dollars originally set aside for state and local governments in the American Rescue Plan (ARP) and instead using them to fund the infrastructure package Congress currently is debating. Indeed, President Biden and a bipartisan group of 22 senators agreed to “repurpose unused relief funds” as a financing source, though a White House fact sheet was not clear about how much or how those dollars would be shifted.

Does the rob-state-Peter-to-pay-infrastructure-Paul idea have merit? Here’s what we know.

According to the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO), states are on track to spend 3 percent more in fiscal year 2021 compared to one year earlier but 2 percent lower than their pre-pandemic projections. That is, while many states will spend more this year, they are still digging out of the fiscal hole caused by the pandemic. The federal assistance—the ARP plus the CARES Act and the COVID-19 Economic Relief Bill—was meant to help close that gap.

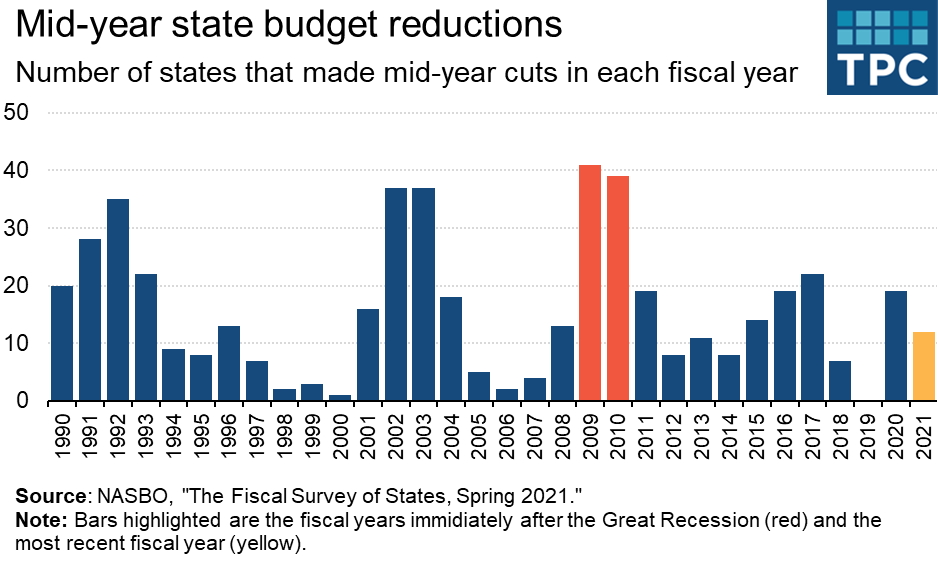

And, so far, it’s succeeding. NASBO reports only 12 states made mid-year budget reductions in fiscal year 2021 (for most states, this was July 2020 to June 2021). By comparison, the vast majority of states made mid-year budget cuts in the aftermath of the Great Recession: 41 states in fiscal year 2009 and 39 in fiscal year 2010.

However, while nearly all states passed budgets on time this year, it will take time for organizations like NASBO to collect summary data on how this year’s spending (that is, fiscal year 2022 in most states) compares to prior years. Further, many states have not yet said how they intend to use ARP funds, which makes it difficult to get a firm grasp on the fiscal position of all 50 states.

But we do know that while nearly all states are doing better than expected there remains a large disparity in states’ post-pandemic economic and fiscal performance. Even before the economy fully opened up, tax revenue was increasing (for various reasons) in states such as Arizona, California, Idaho, and Wisconsin. But at the same time revenues remained relatively low in Alaska, Hawaii, Nevada, and Texas—mostly for reasons related to (the lack of) tourism and (volatile) energy prices.

In the states where the ARP dollars proved to be a windfall, you are indeed seeing some big tax cuts but also a lot of pandemic-related policies. For example, many of the tax cuts are states expanding their earned income tax credits which specifically target the low-income workers most affected by the economic downturn.

However, for many other states, the ARP dollars remain needed help. In these states there’s not much “news” because the story is what didn’t happened: large tax hikes and big spending cuts were not needed to balance the budget because federal aid filled that gap.

Did states need the federal relief money? They almost surely did. Do they still need it? In part because of successful federal action, some don’t. But some clearly still do. As is often the case, the federal debate is missing that nuance. But it is important to keep in mind.