President-elect Joe Biden has proposed major changes to the corporate income tax regime, including:

- Raising the federal statutory corporate income tax rate from 21 percent to 28 percent

- Offering a 10-percent “made in America” tax credit for qualifying investments that support domestic manufacturing

- Replacing the current-law tax on global intangible low-tax income (GILTI) with a 21% country-by-country minimum tax on foreign earnings

- Introducing a 15% minimum tax on global book income

How would these measures—just part of Biden’s much larger tax agenda--impact US corporate income tax revenue and investment? This blog considers the effect of domestic tax reforms (the first two items in the list above), and a future blog will look at international tax reforms.

Since the US corporate income tax largely falls on above-normal profits, or “rents”, a statutory rate increase is a relatively efficient and progressive way to raise revenue. Biden’s 10-percent “Made in America” tax credit (MIATC) would offer a substantial marginal subsidy for qualifying investments. The combination of the rate increase and the tax credit would likely reduce overall corporate investment slightly but significantly shift those investments toward manufacturing.

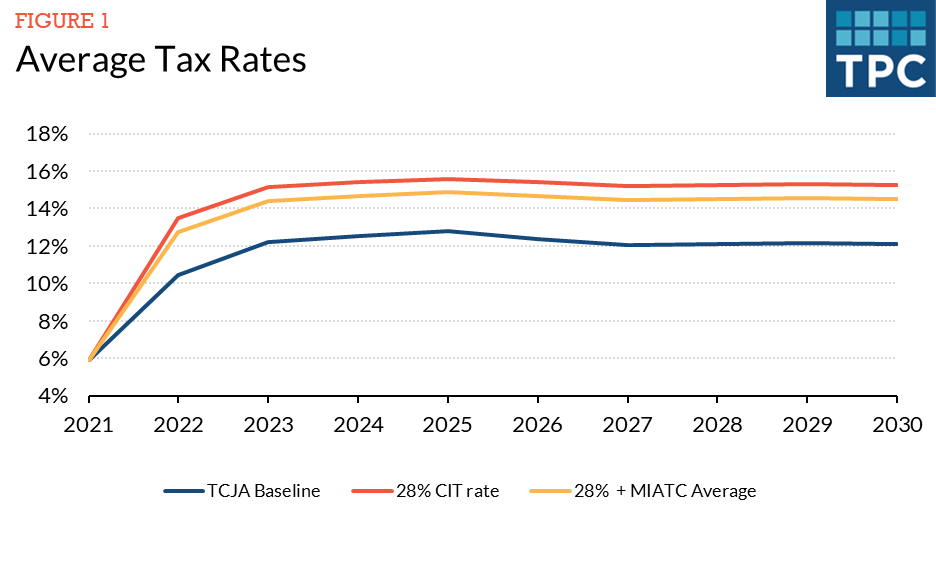

TPC estimates that a 7-point increase in the corporate tax rate starting in 2022 would raise about $740 billion over the 10-year budget window (2021-2030). This would increase the average tax rate on corporations—the ratio of income taxes paid to total profits—by about 3 percentage points (figure 1).

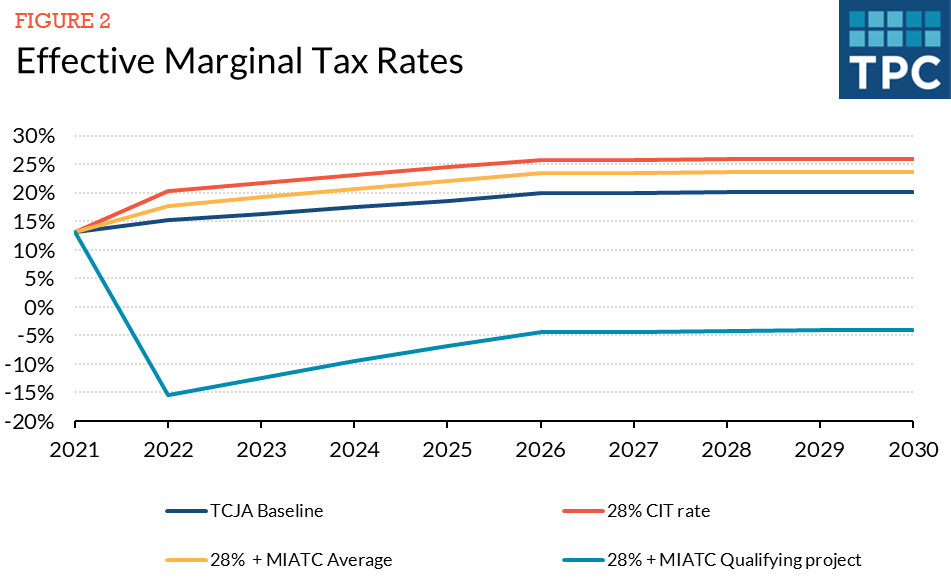

The effect of taxes on businesses’ incentive to invest depends on the effective marginal tax rate (EMTR)—the tax burden on a new project that earns a normal return after taxes. Raising the corporate income tax rate to 28 percent would increase the EMTR by an average of 5.5 percentage points over the budget window (figure 2).

However, the corporate rate increase would be tempered by Biden’s proposed MIATC. The credit would allow firms to claim a tax credit equal to 10 percent of the value of investments that revitalize closed or closing facilities, retool existing manufacturing facilities, repatriate US jobs, or expand US production and employment. This effectively constitutes a government subsidy for 10 percent of qualifying investment costs.

The Biden campaign did not provide many details of the MIATC: Which investments would qualify? Would the credit reduce their depreciable basis? Would it be fully refundable?

The TPC analysis interpreted the credit broadly, assuming that 50 percent of all manufacturing investment would qualify, that the credit would not reduce depreciable basis, and that it would be refundable. This formulation of the tax credit would lower corporate income tax revenues by about $180 billion through 2030, scaling back the average tax rate increase from 3 percentage points to about 2.5 percentage points.

Investments qualifying for the new tax credit would face a much lower EMTR than non-qualifying investments. Indeed, they would receive a substantial tax subsidy, as shown by the light blue line in figure 2. On average, the combination of the higher corporate income tax rate and the new tax credit would increase the economy-wide average EMTR by about 3.5 percentage points. This would likely lower overall corporate investment by about 1 percent and generate a significant shift from non-qualifying to qualifying investments in the manufacturing sector.

The current US corporate income tax is in many respects a tax on profits in excess of the normal return on capital, or “rents”. A 2016 study by the Treasury’s Office of Tax Analysis found that excess profits now account for at least 75 percent of the U.S. corporate tax base. Moreover, the very generous depreciation rules that were included in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (bonus depreciation) lower the marginal tax rate on equipment investment to zero—or even provide a marginal subsidy, if the purchases are debt-financed.

Since rent taxes impose no burden on marginal investment, they distort investment decisions much less than income taxes, which also tax the normal rate of return. Both corporate income and rent taxes are highly progressive because corporate share ownership is concentrated among the wealthy. However, rent taxes are even more progressive because they have less impact on investment and therefore labor productivity, so they are less likely to depress wages.

As a result, raising the corporate income tax can be a relatively efficient and progressive way to generate revenue.