A key feature of President Biden’s effort to expand government support for low-income families is its increase in the earned income tax credit (EITC) for workers without qualifying children living at home. But, as designed, the so-called childless EITC adds to significant marriage penalties and divorce bonuses for many low earners who marry other low earners with children. And Biden’s effort to enhance the credit makes the problem worse.

This continues a long-standing trend where federal policymakers appear to favor marriage for older and richer people whose children have grown while penalizing younger and poorer parents and stepparents in their child-raising years—that is, those years when child development is often enhanced by the presence of two adults. Fortunately, Congress could eliminate much of this EITC marriage penalty with some relatively modest design changes.

At Biden’s urging, Congress nearly tripled the childless EITC to a maximum of $1,502 when it passed the American Rescue Plan (ARP) in March. Now, the White House would make those changes permanent under the American Family Plan (AFP) and its proposed budget.

For workers in households with children, today’s EITC provides valuable support. Tripling the credit for childless workers would modestly expand work support for childless workers as well.

But there is a problem: marriage of a childless worker to a single head of household often makes the childless worker benefit disappear and simultaneously reduces the size of the benefit for the now married household below that it received with a single head. Yet marriage, like work, often enhances the economic, not just social, well-being that the credit aims to promote.

Childless workers have long been among the most neglected people in the social welfare system, so it makes sense to pay some attention to them. In Man Out former New York Times reporter Andrew Yarrow describes how millions of single low earners have become largely disaffected from both society and work life. They often get government attention only when they develop addictions or commit crimes.

The EITC has followed that pattern of neglect throughout its history. Originally designed as an alternative to the nation’s primary welfare program, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), the EITC has kept that child focus ever since, largely benefitting single heads of household but leaving out both childless workers and many low earners who marry other low earners.

The EITC’s marriage penalties derive from two factors: the way it phases out quickly when income rises above modest levels and the effective prohibition against married couples filing single returns.

Here’s an example:

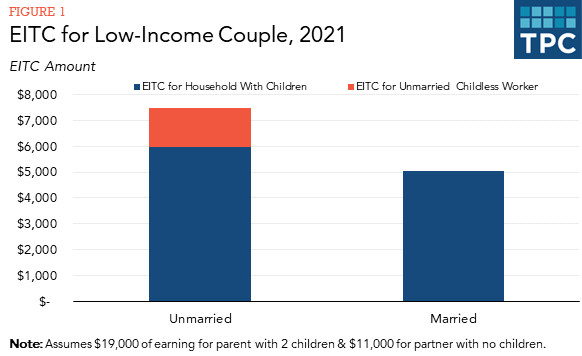

Suppose a male childless worker with $11,000 of earnings marries a female single head of household with two children and $19,000 of earnings. Then the formerly childless worker automatically loses his entire EITC because he is no longer “childless.” Meanwhile, the former single parent loses $956 of EITC because the couple’s combined income is high enough that married household’s benefit begins to phase-out as well. Combined, marrying costs the couple close to $2,500 of EITC benefits (Figure 1).

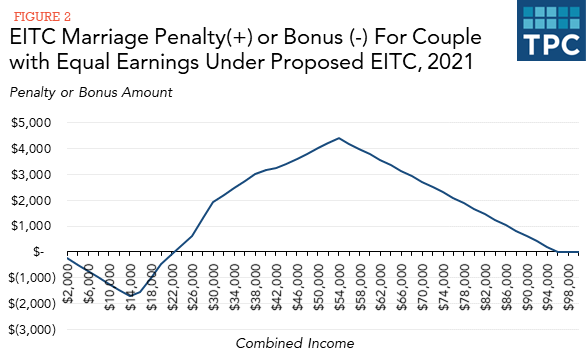

Part of the problem is the basic design of the EITC within our overall tax system. This couple would lose $956 in EITC even if there were no childless worker benefit. In 2021, a married couple with two children and as much as nearly $100,000 of combined income (equally divided) can lose significant EITC benefits by failing to divorce (Figure 2).

For example, if each individual earns $25,000, together they’ll lose about $4,000 by marrying or staying married even though neither would have been eligible for the childless EITC. The worst-case penalties apply to couples who each have children. A couple with four children would lose more than $7,500 of EITC if each came into the marriage as a head of household with two children.

These penalties can be reduced or eliminated in at least two ways: Benefits could be phased out at higher income levels, as the AFP does with the much broader proposed expansion of the child tax credit (CTC); or work subsidies could be tied to each individual’s earnings rather than the couple’s. Social Security and some state income tax systems already do this.

Our tax and transfer systems provide hundreds of billions of dollars annually in marriage bonuses to many families other than those with low incomes. The basic rate structure of the income tax provides marriage bonuses for most middle- and upper-middle income couples with an uneven split of earnings, often dampening or eliminating the marriage penalties from any EITC if still available. Social Security not only largely avoids marriage penalties but it also provides more than 7 million older individuals with additional spousal or survivor benefit—effectively a marriage bonus—for which they contribute nothing extra.

The willingness of congressional Democrats and the Biden Administration to expand family supports through the CTC and EITC makes this an ideal time also to reconsider the credit design for low-wage couples who marry.

Such reform might further seek out the advantages to separating subsidies for work from those for children, now combined awkwardly in the existing EITC. Supports for work and childrearing both have merit but serve different purposes. But by simply increasing credit amounts without redesigning the programs the Biden Administration and Congress would miss out on an important opportunity. Additionally, larger marriage penalties might erode public support for future EITC expansions for all low earners, whether childless or not.