A group of Senate Democrats has introduced a bill to impose tariffs on imports of carbon-intensive goods and fossil fuels equal to the domestic environmental policy costs of producing those goods in the US. The bill’s formula for calculating those costs is flawed. But introducing a border carbon adjustment (BCA) without first instituting a robust national carbon pricing policy constitutes a more serious error.

The “Fair, Affordable, Innovative and Resilient Transition and Competition” (FAIR) Act would impose import tariffs on iron, steel, aluminum, cement, and fossil fuels as well as goods composed largely of these materials.

The tariff rates would equal the industry average domestic environmental cost of producing those goods in the US, including the cost of complying with “any Federal, State, regional or local law, regulation, policy or program...designed to limit or reduce greenhouse gas emissions.” This would include the Clean Air Act, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions standards for passenger cars and light trucks, and any future clean electricity standard (CES) legislation aimed at lowering carbon emissions.

The tariff would apply to US imports except those from certain low-income countries and from nations that both impose environmental policy costs less than those of the US and do not apply a BCA to US export. Democrats currently plan to include some version of this measure in the budget reconciliation bill they hope to pass later this year

According to The New York Times, the FAIR Act would raise $5 billion to 16 billion annually. By contrast, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that a moderate carbon tax starting at $25 per ton of CO2 could raise about $100 billion per year.

Carbon pricing, which includes carbon taxes and cap-and-trade regimes, is a “source-based” policy that typically applies in the country where emissions are produced. As a result, carbon-intensive goods produced in countries with high carbon prices will be more expensive than the same goods produced in countries with low carbon prices.

BCAs help prevent “carbon leakage,” which occurs when energy-intensive goods production migrates from countries with high carbon prices to those with lower carbon prices due to trade and capital mobility. To prevent leakage, BCAs tax carbon-intensive imports from countries with low carbon prices and/or rebate the domestic carbon price on exports to such countries. Though the concept of a border adjustment is straightforward, in practice BCAs are difficult to design.

However, the US has no national carbon price—only a patchwork of federal, state, and regional fiscal and regulatory measures that affect greenhouse gas production. This complex mix of subsidies and costs results in a net average effective carbon price that is both low and difficult—if not impossible—to calculate.

Both Canada and the EU, which have substantial, progressive carbon pricing policies, are currently designing BCAs. Under the FAIR Act, if they apply them to US goods, their exports to the US would be subject to the US BCA—even though they have much higher average carbon prices than the US.

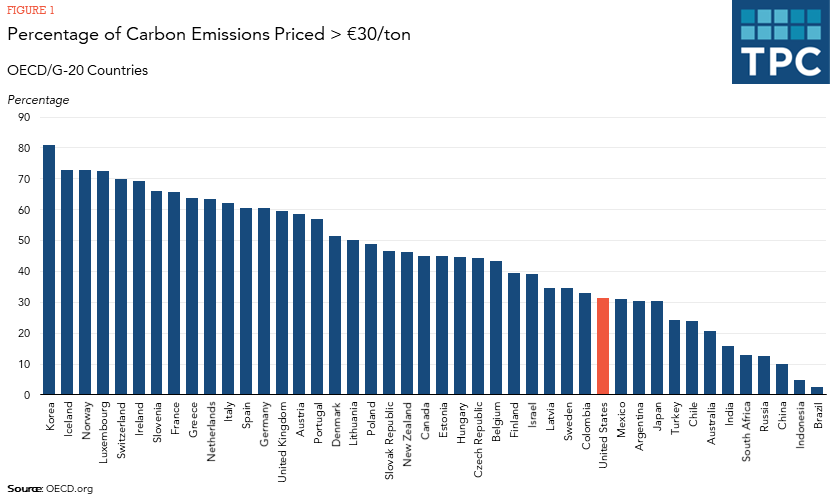

According to the OECD, the US currently prices 31 percent of emissions at or above EUR 30 (US$35) per ton of CO2. By contrast, Canada prices 45 percent of emissions at or above that level, and EU member countries average 55 percent.

Currently, the EU emissions trading system has a carbon price of about US$61 per ton of CO2, and Canada’s federal carbon pricing system has a minimum carbon price of about US$32 per ton. Both jurisdictions plan to increase their carbon prices substantially above those levels. The International Monetary Fund estimates that a carbon price of at least US$75/ton will be needed by 2030, along with continuing future increases, to limit temperature rise to 2 degrees Celsius.

The FAIR Act’s BCA is unusual because it bases tariff rates on regulatory costs as well as carbon pricing policies. It must use this model because the federal government is trying to address climate change largely through tighter regulations. But the bill’s formulas do not accurately measure environmental costs.

Current US carbon pricing policies consist largely of subnational transport fuel taxes and cap-and-trade systems, such as those in California and the northeast. Carbon leakage is an even greater concern at the subnational level, where high goods and factor mobility limit states’ ability to impose significant carbon prices. A minimum federal carbon price similar to Canada’s would greatly strengthen states’ abilities to address climate change.

The political fate of the FAIR Act is uncertain, since Democrats likely will be unable to fit it into special budget reconciliation rules. But even if they could, it’s a classic case of putting the policy cart before the horse. To combat climate change and raise much needed revenue, the US should follow Canada and the European Union (EU) by first instituting a substantial minimum carbon price.