Once the US economy recovers from the COVID-19 crisis, the federal government will need significant additional revenues to reduce its ballooning deficit. Congress and President Biden could build back a better economy—and address climate change—by diversifying the US tax base with environmental taxes.

Earlier this year, the Congressional Budget Office projected the federal deficit would top 10 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2021. The American Rescue Plan Act that Congress passed in March added an additional $1.2 trillion in 2021 net spending, which will push the federal deficit above 15 percent of GDP.

Also in March, Biden proposed spending another $2 trillion for infrastructure improvements and other domestic priorities over the next 8 years, partially offset by corporate tax increases. Sizeable new revenues will therefore be needed to restore the US to fiscal sustainability, an issue even before the pandemic.

The White House is likely to budget revenue expansions almost exclusively with higher corporate and individual income taxes. To pay for his infrastructure plan, Biden proposes several corporate tax increases, and he’ll likely fund his soon-to-be-announced social spending initiatives with higher taxes on wage and investment income of high-income households.

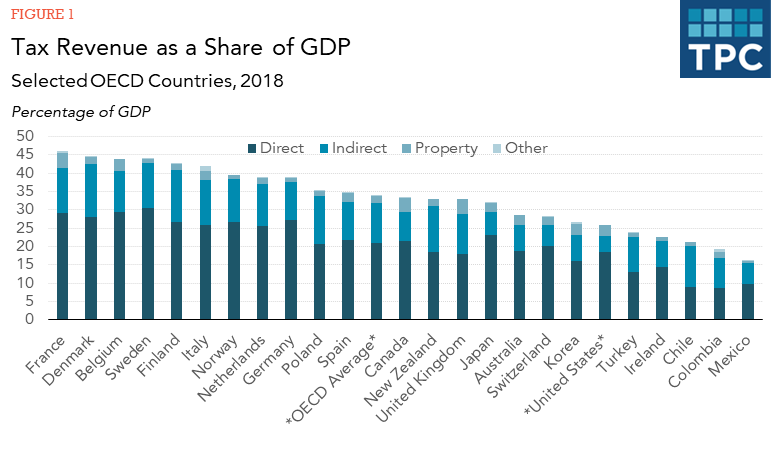

As a relatively low-tax country, the US has ample room to increase tax revenues. Before the COVID-19 crisis, the US raised about 25 percent of GDP in tax revenue, almost 10 percentage points less than the average OECD country.

But financing new initiatives entirely with income taxes would likely slow the economic growth the White House wants to promote. In general, direct taxes on income and payroll burden investment and labor. Thus, they are more distortive than indirect taxes on consumption, which increase labor costs but exempt the return to savings.

Though a low-tax country overall, the US is heavily reliant on income taxes, which account for 70 percent of its total government revenue. This compares with an OECD average of 62 percent.

Thus, the US should look to indirect taxes to raise additional revenues. Currently, state and local retail sales taxes in the US generate only about 2 percent of GDP in revenue, compared to an OECD average of 7.1 percent. US excise taxes raise about 0.8 percent of GDP, compared to an OECD average of 2.4 percent.

Specific taxes on goods and services with harmful effects can actually increase economic efficiency by aligning market prices with true social costs. That’s why the most common excise tax bases throughout the world are tobacco, alcohol, and petroleum products, which have harmful health, behavioral and environmental effects.

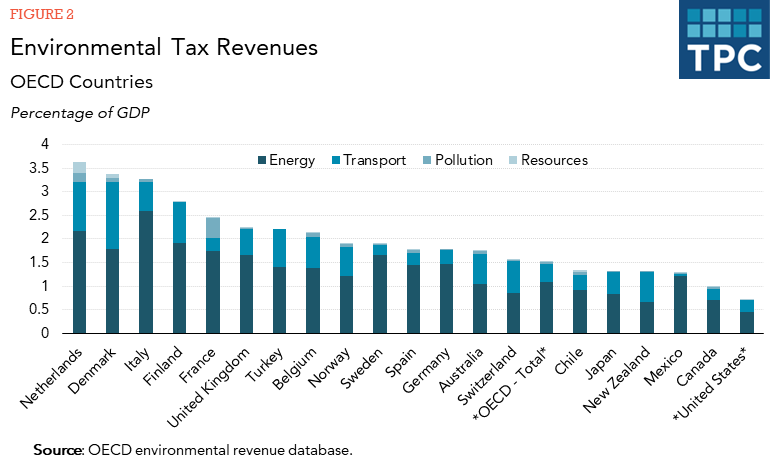

There is a natural synergy between Biden’s goal of combatting climate change and higher excise taxes on fossil fuels. Along with raising needed revenue, higher excises on coal and petroleum products would curb consumption of carbon-intensive goods and encourage investment in cleaner technologies. Given that the US currently has the lowest level of energy and other environmental taxes among OECD countries (figure 2), raising fossil fuel excises seems like a “no-brainer."

However, Biden’s environmental plan – at least what we know so far – relies overwhelmingly on spending and regulation, combined with “green energy” tax subsidies, to achieve its goals.

Critics of higher fuel excises object to these taxes’ regressivity: They tend to take a larger share of income from the poor than from the rich because carbon-intensive necessities such as electricity and fuel account for a larger share of low-income household budgets.

This problem, combined with Biden’s promise to protect households making $400,000 or less from any tax increases, appears to explain why the Biden Administration has rejected the eminently sensible policy of raising the US gas tax.

The motor fuels tax has been frozen since 1993 and is the lowest in the OECD. At 18.4 cents per gallon, it imposes a price of about $18 per ton of carbon dioxide emissions, far below the Administration’s own estimate that the social cost of carbon is around $51 per ton.

An effective solution is taxing fossil fuels at their full social cost--which includes not only carbon emissions but also local air pollution--and offsetting the burden on lower-income households with other policy measures. For example, the cost of a carbon tax could be rebated to low-income households through an expansion of the earned income tax credit.

Finally, the real harms of under-taxing fossil fuels are regressively distributed. Research on environmental justice shows that low-income and minority communities suffer disproportionately from the negative effects of both local pollution and climate change. Correcting the distorted consumption patterns that give rise to these effects would raise the real quality of life in a progressive manner-- and help pay for some of Biden’s ambitious domestic policy initiatives.