The dependent exemption, the earned income tax credit (EITC), and the child tax credit (CTC), supported at times by Republicans and Democrats alike, help bolster families financially, reduce poverty levels, and provide other positive returns to society. These provisions, rather than education, welfare, or nutrition programs, are now the largest category of federal support for children.

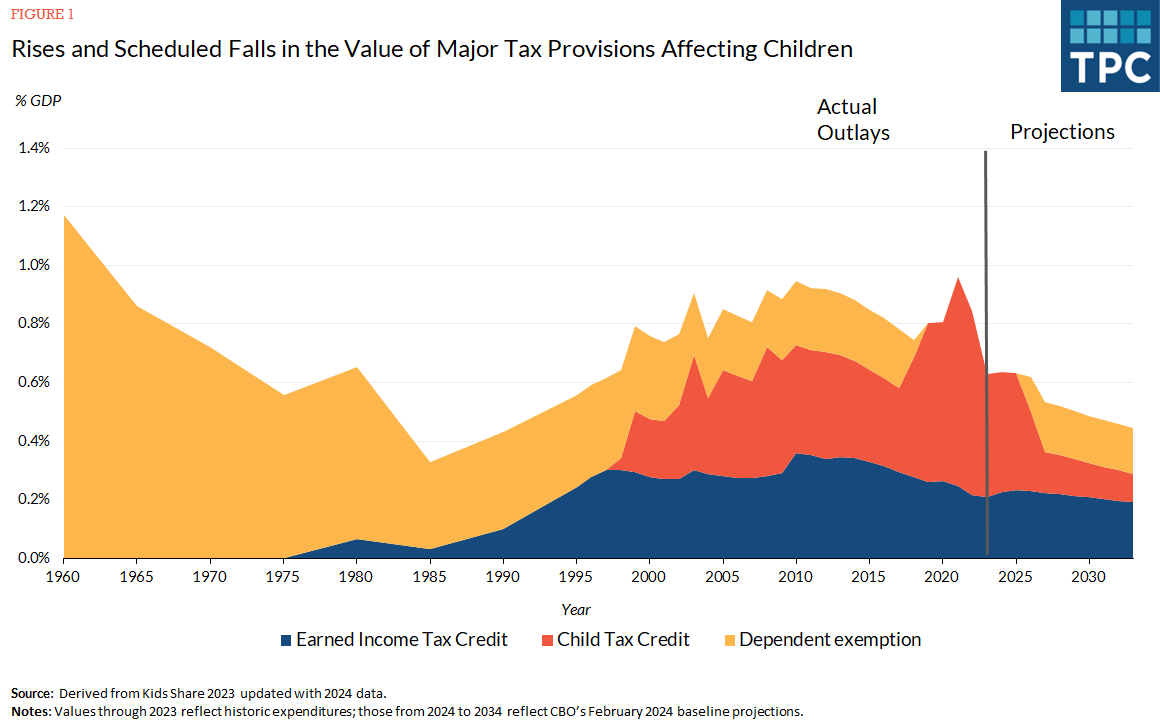

But, as documented by the Urban Institute’s annual Kids’ Share report, spending on each of these tax provisions and the combined total for all three has been on a roller coaster ride. Increases in the child credit and earned income credit under every recent president may lead one to think that the trend has only been upward. However, in 2023, the total for the three was at a low as a share of GDP not seen for almost a quarter century. Under current law, it is scheduled to decline further (see figure).

Expiring provisions of the Tax Jobs and Cuts Act of 2017 (TCJA) at the end of 2025 provide an imperative for Congress to act and an opportunity to rethink these policies holistically.

Legislation built the roller coaster.

The tax credit increases or roller coaster inclines derive almost entirely from periodic legislation that added, at least in nominal terms, to the value of one or other of these three provisions. For example, the TCJA temporarily provided a more costly child credit but eliminated the dependent exemption.

The tax credit decreases, or roller coaster declines, result primarily from not indexing any of the provisions for growth in real income per person. The CTC has never been indexed even for inflation, except for some lower-income households. The dependent exemption was not indexed for inflation until after 1984.

The roller coaster needs repair.

The dependent exemption, EITC, and CTC attempt to fulfill three commendable but sometimes competing objectives: adjusting tax burdens for the ability to pay, encouraging work, and providing family allowances. It is challenging to accomplish all three at a low cost.

The dependent exemption, established in 1917, represented an adjustment for the ability to pay income taxfor families with children and other dependents. Taxing similarly situated households equally, or horizontal equity, has long been a principle of sound tax policy. Here, it requires an adjustment for household size at all income levels. The dependent exemption achieved this result by providing that a certain amount of income, at times set to an amount of income equal to the poverty level, should not be subject to tax.

Congress has increasingly been abandoning that objective by temporarily eliminating the dependent exemption and phasing out the EITC and the CTC at higher income levels. Consequently, as a share of GDP, the dependent exemption alone was more valuable in 1960 than all three provisions in any subsequent year. A much longer history can be found here, here, and here.

The EITC sought to achieve a second objective: encouraging work among low-income families with children. First enacted as a pro-work alternative to the welfare program Aid to Families with Dependent Children, its benefits were increased to meet other objectives, such as helping ensure that someone who worked full-time with children at home would not face poverty. The work subsidies in the EITC largely exclude workers without children at home, and because of how the credit is calculated, most married couples with two earners also lose out. The share of GDP devoted to the EITC has fallen to its lowest level since the mid-1990s and continues to decline.

The CTC, in turn, has moved closer to a “family allowance” approach, with much debate about whether a phase-in, as exists in the EITC, should be eliminated. Eliminating the phase-in is progressive and helps reduce poverty by extending benefits to those who do not work or work too little to be eligible for the maximum credit. When Congress replaced a dependent exemption indexed for inflation with a larger child credit unindexed for inflation through the TCJA, it resulted in a one-time bump up in support for kids but steeper net declines over time.

To avoid these problems, a subsidy for work, including for those currently left out of the EITC, could be separated from the subsidy for children, and both could be increased over time in line with average economic income. But such reforms would add yet more to revenue costs.

Only major budget reform—one that resets priorities in the budget as a whole—likely could achieve all these objectives well.

Or maybe children don’t need to ride this roller coaster at all.

Since 2021’s temporarily expanded CTC expired, many, including President Biden in his State of the Union address, have urged restoring the expanded child tax credit. The House passed a bill that would temporarily restore some child credit for low-income individuals, along with several extensions of business tax subsidies. However, that bill is now stuck in the Senate. And both it and the administration’s proposal would provide increases only through 2025, when TCJA’s expiring provisions run headlong into a budget with huge growing deficits built into the law.

Is there political support for putting such a low priority on children and work in the federal budget? Or is it a byproduct of bad budgeting, with little understanding of the outcomes set in motion? While Congress could increase spending through annual or periodic appropriations, most of the growth in federal spending is automatic, tied to significant growth rates built into the largest entitlement programs. That means most or all revenues that rise as the economy grows have already been committed.

Suppose the federal government followed a workable and sustainable budget process. In that case, we doubt that the public and their elected officials would favor increasing the net tax burdens on families with children relative to other taxpayers.

Scheduled tax increases for families with children under current law provide an opportunity to think through and reset the nation’s priorities.