After years of growth, some states saw cannabis tax collections decline for the first time in fiscal year 2022. But, while politicians occasionally promote marijuana taxes merely as a cash cow for state and local governments, the real story is more complicated. And those revenue declines may even suggest policy success.

Regardless, falling revenues are not discouraging states from pursuing marijuana legalization and taxes. Five states will vote on cannabis taxes this November and politicians are increasingly pushing legalization on the campaign trail. As they do, a new Tax Policy Center report looks at the policy tradeoffs and goals that stakeholders should consider.

There are different types of cannabis taxes, each with pros and cons

The first thing to know is there in not a standard state and local cannabis tax. There are three.

- Percentage-of-price taxes typically work like a general sales tax but with higher rates. State tax rates range from 10 percent in Michigan, Nevada, and Rhode Island to 37 percent in Washington. This is the most popular tax, with 11 states solely using it and five using it in addition to another tax. Local governments also almost exclusively use this type of tax, but their rates are typically capped between 2 percent and 5 percent.

- Weight-based taxes are calculated differently in each of the five states with this tax, but generally cultivators weigh their product, apply a rate (that typically varies by part of the plan), and remit the tax to the government.

- Potency-based taxes are based on the product’s level of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive compound in cannabis. Illinois levies a higher retail tax on high-TCH products, while Connecticut and New York tax per milligram of THC.

Additionally, the state or local governments levy their general sales tax on marijuana purchases in 15 states. This tax affects the purchase price but it is not a cannabis tax.

Each cannabis tax comes with tradeoffs.

A percentage-of-price tax is the simplest to administer and least burdensome to businesses. However, if the tax rate is not increased, collections will slow or even decline as the retail price of cannabis falls.

Weight-based taxes are generally not affected by price, but are onerous to legal sellers. California, Oregon, and Washington all repealed these taxes in part to assist their cannabis businesses.

A potency-based tax can discourage use of high-potency and thus high-risk products while not pushing consumers out of the legal market. However, THC testing still has limitations, and the process adds costs to legal businesses.

Cannabis tax revenue is significant

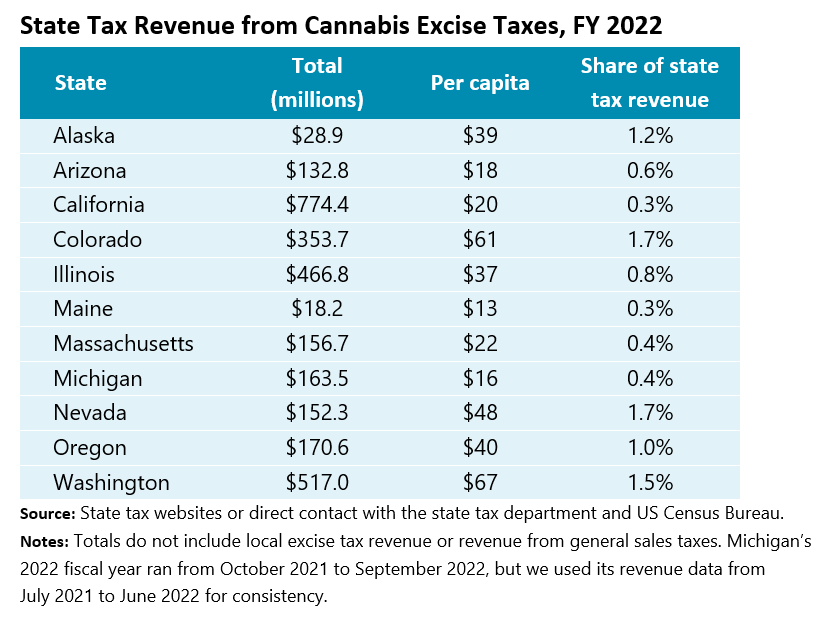

Cannabis tax collections provided at least 1 percent of total state tax revenue in five states in fiscal year 2022—and that doesn’t include local excise taxes and general sales taxes on marijuana purchases.

So why did collections fall in California, Colorado, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington in 2022 after years of strong growth?

First, it’s possible that the 2022 decline was actually the result of a COVID-19-related revenue spike in 2021. That year, consumers had extra income thanks to federal stimulus payments and reasons to purchase a little extra marijuana—picking up weed at the dispensary was more COVID friendly than a trip to the bar.

But it’s also notable that the five states where revenue fell had the longest history of legal and taxable marijuana sales. Thus, there is a chance that in some states the “problem” is successfully bringing more cannabis businesses into the market, meeting consumer demands, and seeing retail prices (but also tax collections) fall.

Or maybe the problem was connected to the tax system in some states.

That complexity is why state and local governments should focus on what they hope to achieve with their taxes and not merely revenue collections.

The goals and tradeoffs of cannabis taxes

We discuss four possible goals in the report: raising revenue for broad government services; supporting programs that remediate past drug-enforcement policies, such as enhancing economic development in harmed communities; addressing negative consequences of cannabis use, such as with drug education; and discouraging demand for highly potent cannabis products.

Except for potency-based taxes, all these goals are reflected in how the revenue is spent. Unlike cigarette taxes, states do not want cannabis taxes to discourage broad consumption of marijuana.

But that creates the conflict: Policymakers want revenue but cannot levy taxes so burdensome that they drive consumers out of the legal market.

California repealed its weight-based tax and reformed its retail tax this summer because policymakers concluded that those taxes were stifling the development of the state’s legal cannabis industry. That is, California’s revenue problems were a warning about its burdensome tax system.

In contrast, both public and private reports suggest Washington created a successful legal marijuana market even with a relatively high statutory tax rate. Its recent revenue decline probably was related, at least in part, to its legal retailers successfully meeting the demand of consumers, not because of a problematic tax system.

A well-designed cannabis tax system can achieve multiple goals. But focusing myopically on revenue growth could create more problems than solutions.