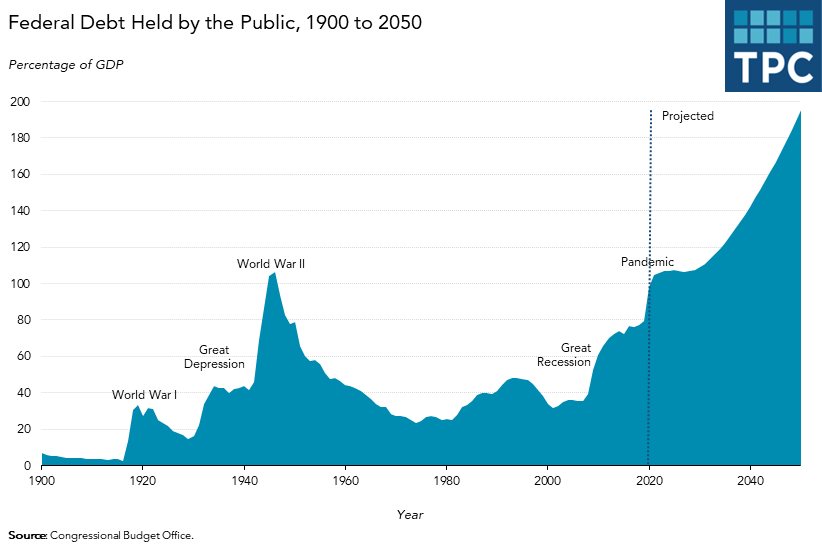

It is hard to overestimate what a dismal fiscal future the Congressional Budget Office foresees. In its new long-term budget estimate, CBO projects that in just 30 years, the national debt will rise to nearly twice the US’s total economic output, from less than 80 percent last year.

As a share of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the federal debt already is as high as it was at the peak of World War II. And CBO projects it will roughly double again by 2050. Even worse, its forecast assumes Congress won’t enact another large pandemic-related stimulus bill (it probably will), and that it will allow many of the tax cuts in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act to expire on schedule in 2025 (it probably won’t).

Greece, with worse food

If the more likely, but more pessimistic, assumptions instead prevail, the debt will rise to 2.5 times the size of the economy, according to an analysis by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. Even in CBO’s more conservative current-law projection, we will be a fiscal Greece, but with worse food and less sunshine.

How is this happening? It is simple really. Continuing the recent trend, the federal government is projected to spend more and more money as a share of the economy—much of it on Social Security and health care—even as the amount of revenue it takes in grows far more slowly.

For instance, in fiscal year 2019, before the pandemic, the federal government spent about 21 percent of GDP, while it raised about 16.3 percent in taxes and other revenues. Under current law, CBO projects that by 2030 spending will rise to 23.1 percent of GDP while revenues increase to 17.8 percent. Under the more realistic CRFB projections, spending will grow to 24 percent of GDP while revenues remain nearly flat at 16.6 percent.

$6,300 less per person

By 2050, CBO forecasts that spending will grow to 31.2 percent of GDP even under current law, while revenues rise to just 18.6 percent. The annual federal budget deficit—the gap between spending and revenue—would nearly triple from 4.6 percent of GDP to 12.6 percent. Under CRFB’s more realistic assumptions, that annual fiscal gap would widen to an eye-popping 16.5 percent of GDP, nearly 1/6 of 2050’s total economic output.

Since these numbers are relatively meaningless to normal humans, CBO tried to make them real. It estimates that with so much money going to finance government debt rather than fund private commerce, the economy will grow by about 0.2 percentage points per year more slowly than if the federal debt remained at pre-COVID-19 levels. By 2050, the Gross National Product (GNP) is projected to be more than 6 percent lower, a shortfall equal to about $6,300 per person per year in today’s dollars.

Paying the vigorish

One reason is that so much money will be diverted to pay interest on the debt, much of it held by foreign investors. The US is getting itself in the position of a gambling addict who constantly borrows from the local loan shark. More and more income goes to paying off the vigorish—the interest—leaving less and less for immediate consumption or long-term investment. And with less investment, future economic growth inevitably slows.

The US was remarkably fortunate the last time it ran up massive debt. After World War II, it dominated the global economy. With manufacturing booming and GIs returning to work, the nation was able to pay off lots of those war IOUs—and it still took almost two decades to get the national debt back to where it was before the war.

“If something cannot go on forever”

We probably won’t be so lucky this time. The US economy no longer dominates the world. Our labor force, a key driver of economic growth, is barely growing as the massive Baby Boom generation retires and dies. Maybe some new burst of technology-driven productivity will save us. Maybe the advocates of modern monetary theory are right and the government can finance its debt indefinitely by printing money, without causing inflation.

If not, the US may be headed for a period of significantly higher taxes and reduced government spending. When that will happen is not predictable, though could be triggered by some future spike in interest rates. But a debt that is twice the size of the economy seems, um, improbable.

As the late economist Herb Stein said, “If present trends can’t continue, they won’t.” or maybe it was, “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.” Either way, my bet is that in the medium term, federal taxes are going to rise as the nation is forced to address an ever-growing national debt.