As another season of record-breaking heat, wildfires, and hurricanes unfolds, Congress is debating how to address climate change and fund green infrastructure in its $3.5 trillion budget reconciliation legislation. Though Democrats have declared ambitious goals for addressing climate change, they continue to shy away from carbon pricing in favor of tax breaks for renewable energy. But renewable energy tax credits are less effective than a carbon tax at promoting decarbonization—and of course they cost the Treasury money rather than raising it.

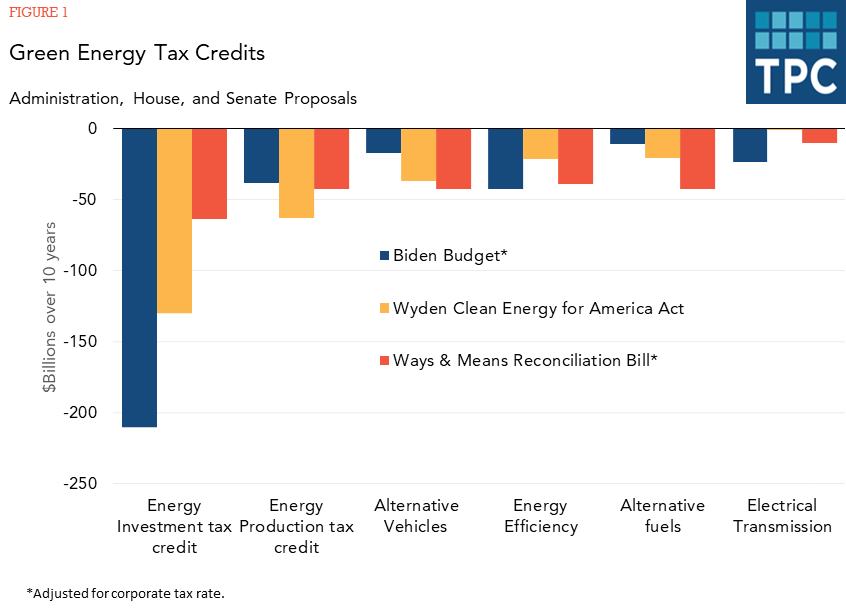

Energy tax measures proposed by President Biden, Senate Finance Committee Chair Ron Wyden’s (D-OR) Clean Energy for America Act, and the House Ways & Means committee’s recent tax bill are generally limited to tax credits for renewable energy and conservation. The largest provision in all these plans is the investment tax credit for renewable energy. Adjusting for the different corporate income tax rates assumed in these proposals, the White House proposal is the most generous, followed by the Wyden and Ways & Means proposals.

The White House and Wyden proposals—but not the Ways & Means bill—would also end existing tax breaks for fossil fuel production. This logical first step would raise about $3 billion a year at current tax rates. Wyden would also end carbon sequestration credits for carbon dioxide (CO2) stored underground in the fuel extraction process. This proposal would raise net revenue despite increasing the credit for other types of sequestration – from $35 per ton of CO2 to $150-$175 per ton.

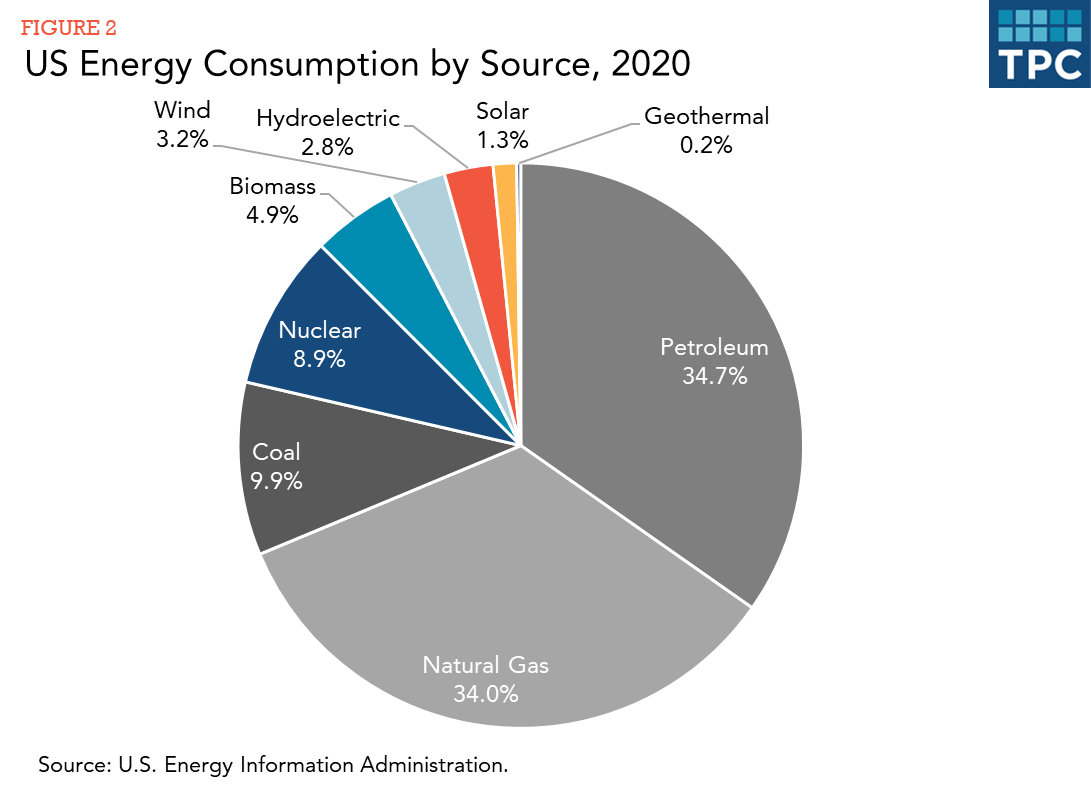

While tax incentives for renewables make clean energy cheaper, they do nothing to raise the cost of dirty energy to reflect the pollution it causes. Given that fossil fuels account for almost 80 percent of US energy consumption, this ignores a powerful policy lever. Carbon pricing could more effectively lower emissions and also augment the effect of green tax credits.

Critics of carbon pricing say it would harm the economy by raising energy costs. But burning fossil fuels imposes direct (though unpriced) costs through both global warming and local air pollution. As climate change accelerates, those direct costs—which the Department of Energy estimates at $190 billion per year for the US—are becoming more obvious in the form of extreme weather event damages.

Charging energy users for the true cost of fossil fuel consumption would improve economic efficiency. Higher prices would motivate consumers to conserve energy and encourage businesses to invest in renewable energy. Since 2018, only a third of US power companies have had positive tax liabilities and could thus fully benefit from the energy tax credit.

And even a modest carbon tax could raise substantial revenues. A recent study finds that a broad-based levy of $15 per ton would raise about $75 billion annually, or 0.3 percent of GDP —a critical consideration as the federal deficit and public debt soar toward World War II highs.

Currently, five bills in Congress call for some form of carbon tax, ranging from $15-$59 per ton of CO2 equivalent. All call for real annual rate increases of at least 6 percent to 10 percent, and most include further increases if targeted emissions reductions are not met. The International Monetary Fund estimates it will take a carbon price of at least $75 per ton by 2030 to maintain sustainable levels of global warming.

To be politically viable, revenue proposals must address the equity issues that carbon pricing presents. There are at least three: Carbon taxes disproportionately burden lower-income households. They don’t specifically address environmental justice issues—the concentration of pollution in low-income and minority communities. And they hurt residents of fossil fuel producing communities.

Regressivity could be addressed by progressive carbon dividends. While a carbon tax would reduce local air pollution by reducing overall fossil fuel consumption, additional measures would be needed to address pollution “hot spots.” And transitional funding is needed for communities that rely on fossil fuel production.

Accordingly, most Congressional carbon tax bills include some combination of means-tested carbon dividends, investments in infrastructure and environmental justice, and transitional funding for fossil fuel workers and communities.

Senate Democrats have reportedly considered a carbon tax of $15 per ton of CO2 equivalent to help fund the $3.5 trillion budget reconciliation. However, there does not appear to be broad support for the measure.

Any sensible energy tax reform should eliminate existing subsidies for fossil fuel extraction, but it will take more to tackle climate change. Even a modest carbon tax could raise significant revenue and curb emissions more effectively than green tax credits alone. If the federal government is paying companies $35 for each ton of CO2 they extract from the atmosphere, shouldn’t it charge at least a fraction of that for putting it there in the first place?