In 2017 and again in 2020, Congress made deficient—but temporary—changes to the federal income tax deduction for charitable giving. By significantly increasing the standard deduction, the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) created an environment where fewer than 10 percent of households deducted their gifts to non-profits. Then twice in 2020, Congress created a badly designed above-the-line charitable deduction of $300 for non-itemizers. The TCJA changes expire in 2025 and the above-the-line deduction expires at the end of this year, Congress must decide on what type of charitable incentive it wants in later years. Bills have been proposed to restore some of those lost incentives, including a universal deduction with few limits and a nonitemizer deduction up to one-third of the standard deduction.

In a new brief, we, along with our colleagues Chenxi Lu and Aravind Boddupalli, examine how Congress can maximize benefits to those who rely on charities at whatever revenue cost Congress is willing to entertain. These reforms include providing a universal deduction for contributions above a minimum amount, tying donations to tax filing season, and improving compliance through better reporting requirements.

It’s easy to design a bad subsidy. For example, the $300 charitable deduction provided charitable recipients in 2020 with as little as $100 million at a cost of $1.5 billion in foregone federal revenue. Since most donors already give more than $300 annually, the subsidy creates an incentive for almost no one. And the IRS has almost no way to audit bogus claims, effectively making the $300 deduction available to any non-itemizer, whether they donate to charity or not.

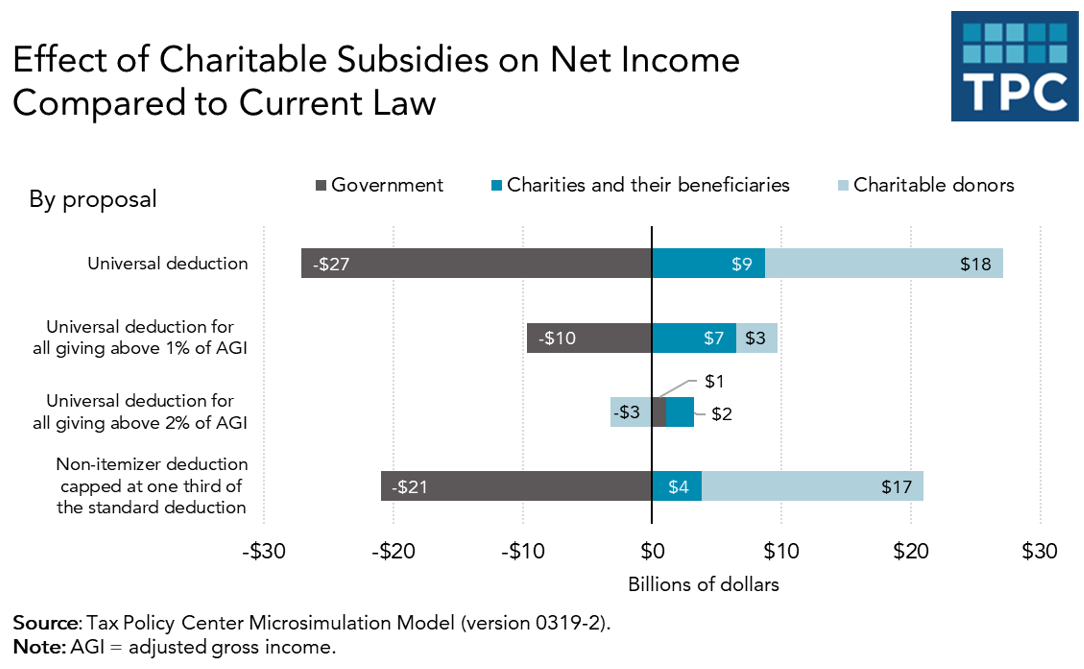

To better understand the effectiveness of the charitable deduction, we created a balance sheet that shows how income of government, taxpayers, and charitable recipients changes under various proposals. Additional contributions represent transfers that flow through charities to their beneficiaries, while the change in the taxpayers’ net income equals their increase in contributions less their additional tax saving.

We first studied an unrestricted deduction that would allow both itemizers and nonitemizers with a positive tax liability to deduct their contributions. While this would create a new tax break for many households, it would be very inefficient at helping the beneficiaries of charities since most of the subsidy would go to those who would have donated anyway. An additional downside: Many itemizers would switch to the standard deduction when it, plus the universal charitable deduction, would reduce their taxes by more than if they continued to itemize. Though not the target of the new subsidy, they would garner a significant share of it without increasing their giving.

On net, an unrestricted charitable deduction would have lowered federal revenue in 2019 by about $27 billion but increased contributions by only $9 billion.

We also examined several alternative forms of a universal deduction. One version would allow a single deduction for itemizers and nonitemizers alike only for contributions in excess of 1 percent of the taxpayer’s adjusted gross income (AGI), and another would subsidize contributions only in excess of 2 percent A third would provide a separate deduction (akin to the $300 deduction allowed for 2020) for nonitemizers for any giving up to 1/3 of the standard deduction, for example, up to a little more than $8,000 in 2020 for most married couples.

Compared to an unrestricted universal deduction, a 1 percent floor would reduce contributions by about 25 percent but cost only one-third as much. Put another way, absent placing a 1 percent floor on the universal deduction, the government would lose an additional $17 billion in revenue, but generate only about $2 billion extra for charitable recipients. The rest would be an additional windfall for taxpayers. Any floor also makes a more universal deduction more progressive by eliminating some deductions from current itemizers with little effect on their incentive to give.

A universal deduction above 2 percent of AGI increases charitable giving while raising revenues for government. The nonitemizer deduction up to one-third of the standard deduction would have cost more than $20 billion in 2019, but increased contributions by less than $4 billion. The proposal provides no incentives for those who give in excess of the ceiling and spends a lot on higher income taxpayers who already itemize charitable contributions but switch to the standard deduction.

Is there a sweet spot where government can increase giving without any loss in revenues? We found that a floor of 1.9 percent would just about break even for government under current law, while raising contributions by about $2.5 billion. If Congress were to restore subsidies to pre-2017 levels, a revenue neutral floor of less than 1 percent would efficiently promote giving.

Congress also could allow taxpayers to make charitable donations up to the date they file their income tax returns or April 15, whichever comes first, something they do now with contributions to individual retirement accounts. This would generate additional giving that would be a significant multiple of any additional cost. Finally, Congress could limit cheating by requiring electronic reporting of charitable contributions to the IRS by non-profits. Tax gap studies consistently have demonstrated that third-party information reporting is strongly related to better compliance.

We very much encourage members of Congress to ask the Joint Committee on Taxation or the Congressional Budget Office to offer them various options, along with estimates of revenue foregone and the distribution of those revenues among charitable beneficiaries and donors. A well-designed, enforceable, and more universal charitable incentive can send a strong, reinforcing signal that we define ourselves and our nation partly by our generosity. Instead of extending the current poor policy, Congress should consider alternatives that best achieve that goal.