Aid for state and local governments remains a sticking point in Congressional deliberations over additional relief to address the economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic. Some argue that states do not need assistance because of better than expected tax collections. But the State and Local Finance Initiative’s data show the actual revenue losses experienced by the states are deep and widespread, if not universal.

The new state revenue data also paint a clear picture for how Congress can best target federal dollars where they are needed most.

What’s going on with state tax revenues?

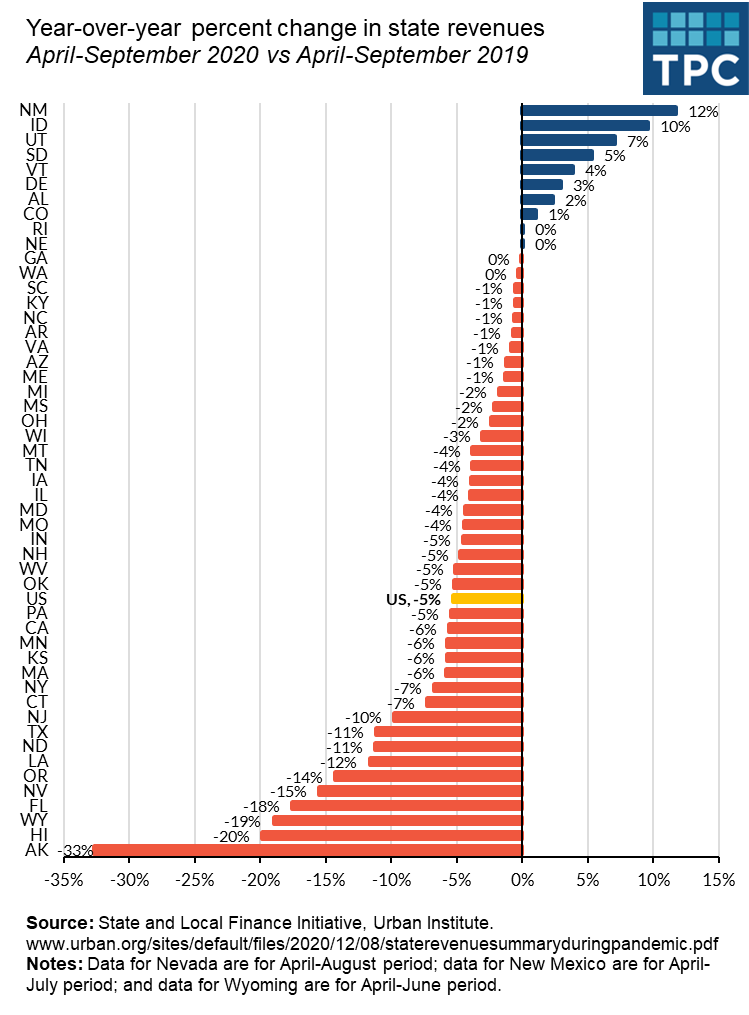

In total, state tax revenues declined 5.3 percent from April to September compared with the same period a year earlier according to our preliminary data. But there is a lot of variability across states.

Forty states reported declines in overall tax collections, with 10 states reporting double-digit declines. But eight states reported growth in receipts, and in two states revenue growth was essentially flat. (Note that DC is not included in this data release.)

The steepest revenue declines were in states with a relatively high reliance on tourism and hospitality activities (e.g., Hawaii, Florida, and Nevada). States that depend heavily on the oil industry (e.g., Alaska and Wyoming) also experienced deep reductions in tax collections.

At the other end of the spectrum, the states that have seen some growth (or a smaller rate of decline) included those that: levy sales taxes on grocery food purchases (e.g., Idaho, South Dakota, and Utah); did not experience as many COVID cases in the spring or summer or did not mandate statewide lockdowns (e.g., Idaho and South Dakota); or enacted tax rate increases for fiscal year 2020 (e.g., New Mexico).

Comparing states’ revenue performance from April to September to the same period during the prior year isn’t perfect. The typical approach would be to compare calendar year quarters or state fiscal years. However, this alternative 6-month range is useful because a number of states moved income tax filing deadlines from April to July this year due to COVID-19 and so shifted the receipt of income tax revenues.

That delay generally shifted the receipt of revenue from one fiscal year to another. (State fiscal years run from July to June in 46 states.) However, we find that 15 states counted income tax revenues from July as if they occurred in the second quarter of 2020 and thus were part of their fiscal year 2020.

What does this imply for COVID relief formulas?

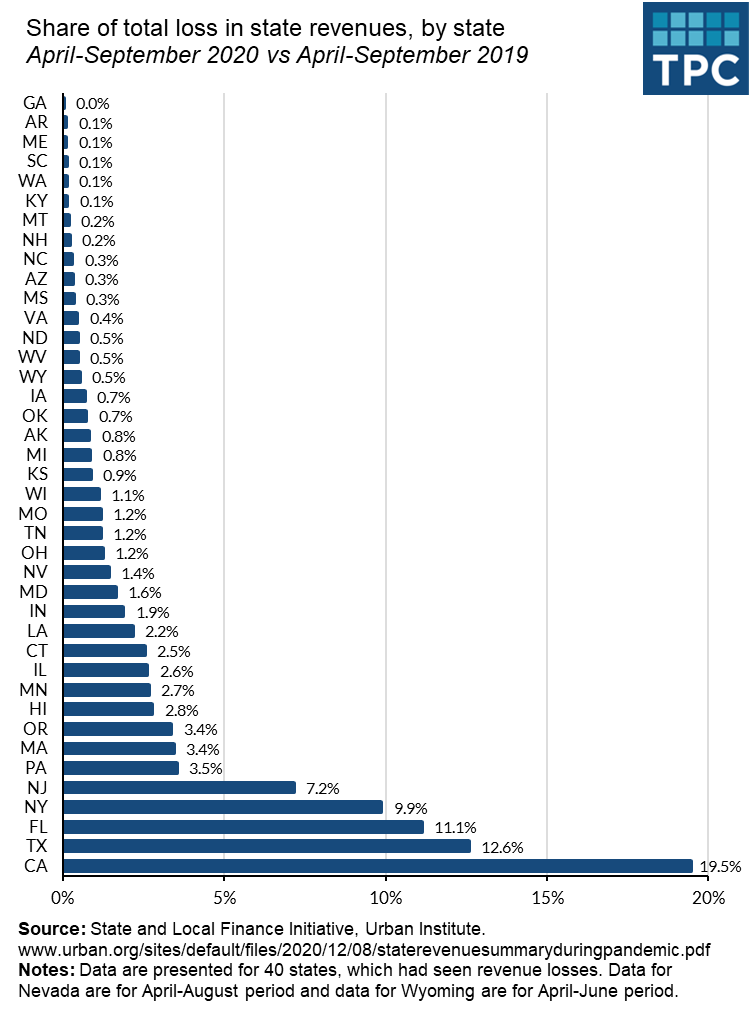

While Alaska experienced the largest state tax revenue decline from April to September, nearly 20 percent of the aggregate decline in state tax revenue came from California.

This makes sense because California also has the largest population, economy, and tax revenues of any state. States with the next-largest shares of the total reduction in state tax revenues from April to September were also large states: Texas (12.6 percent), Florida (11.1 percent), and New York (9.9 percent). But the shares of state revenue losses were larger than population shares in those four states. Thus, the amounts of aid they would receive from the federal government under a revenue loss-based formula would be larger than under a population-based formula. On the other hand, 35 states would receive less money if aid were based on revenues instead of population.

If Congress seeks to target state relief in a way that would help offset revenue losses, assistance should be based on the comparison of revenue collections over the same period for 2019 and 2020. Of course, it is important to be mindful that state tax changes could have offset some of these losses and that some states (and different states) might see even deeper revenue losses in the coming months.

Don’t forget local governments and lags

Our data reflect only state revenues. Other levels of government, particularly cities, will also need aid.

In considering relief legislation, Congress should also not forget that states and localities may not immediately see a drop in tax collections as a consequence of the pandemic-induced recession. Lags can range from a quarter (for sales taxes), to a year (for income taxes), to perhaps three years (for property taxes).

The fiscal and economic effects of the pandemic on state and local budgets are likely to be long lasting. Getting through 2020 is only the beginning. Continued support may be needed depending on the trajectory of the coronavirus and the pace of economic recovery.

But basing federal relief aid to subnational governments on actual revenue losses since the onset of the pandemic would be a good first step.