It’s always tempting to exaggerate the importance of the latest big fight in Congress. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) made some major policy changes. But big or revolutionary in sheer dollars? No. Most of the major provisions of the new law will move around just a fraction of one percent of total economic output.

Even the changes in the Biden Administration’s original Build Back Better plan were modest relative to the increases in spending and revenues already scheduled in current law.

And IRA was much smaller, though it showed Congress and President could make significant policy changes in a fiscally prudent way.

It made a large political leap of committing the US in deed, not just word, to attacking global warming. It reduced Medicare drug costs modestly by championing competitive pricing and temporarily lowered health insurance costs a bit for some middle-class purchasers. It increased taxes modestly for some corporations with a new minimum tax and a tax on stock buybacks. And it began making up for a decade of IRS budget cuts.

But based on new Congressional Budget Office estimates, here is some valuable context about the size of the bill:

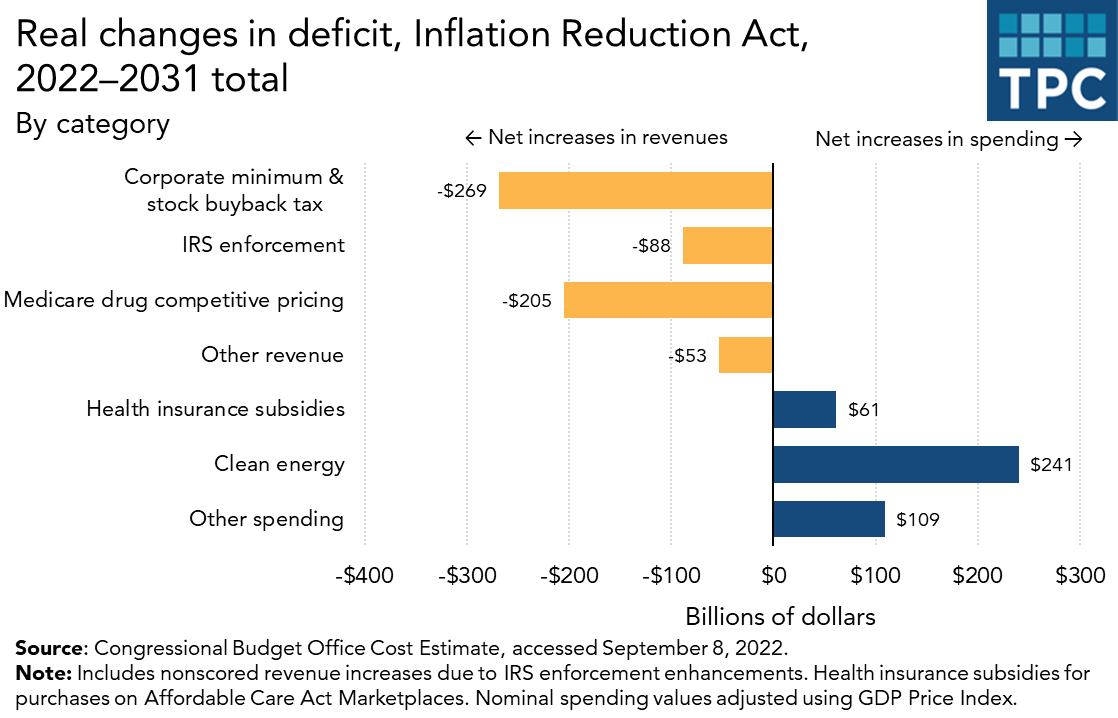

None of the major spending or tax changes entails a total increase or decrease of more than $270 billion over ten years in real, inflation-adjusted dollars. That’s only about 1 percent of this year’s GDP of $25 trillion and well less than 0.1 percent of total GDP for those ten years. IRA will increase total revenues by a bit more than and total spending by a bit less than 0.2 percent of combined GDP over those ten years.

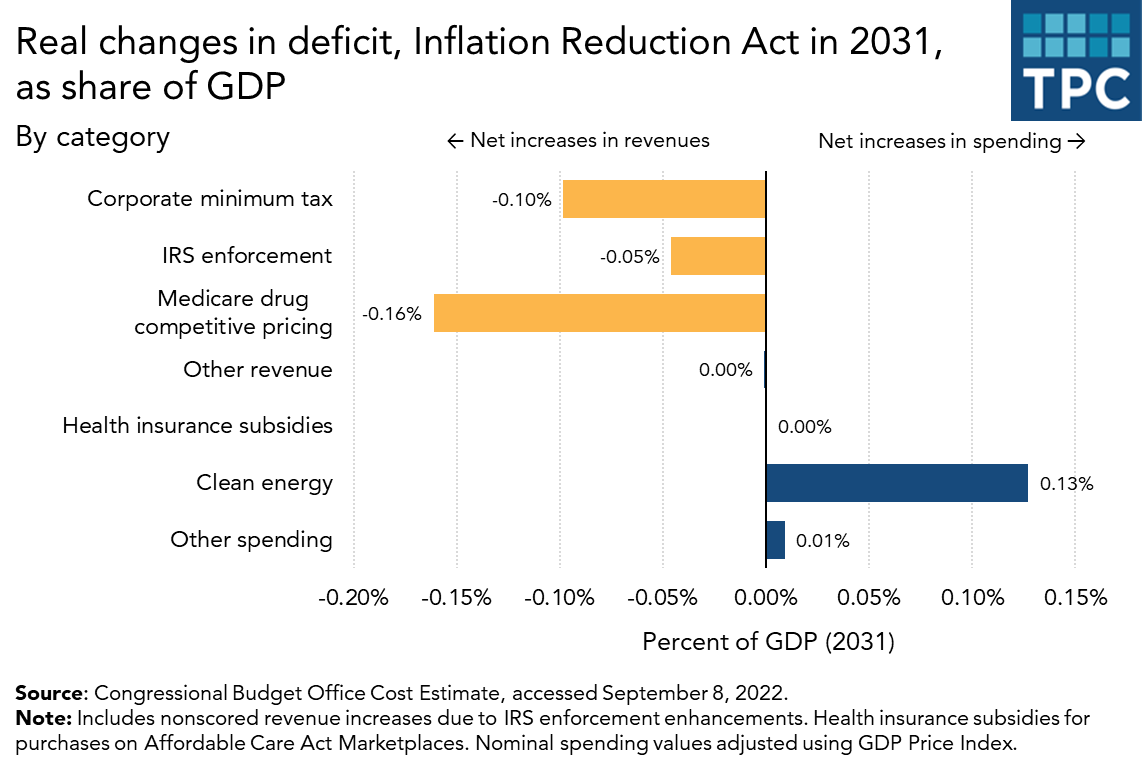

Since many of the bigger provisions, such as Medicare drug pricing reform, are backloaded, whereas increases in Affordable Care Act health insurance exchange subsidies are only temporary, we looked at the impact of these changes in 2031. In that year, counting both revenue increases and spending increases in all major categories as a rough way to measure changes in policy, the changes add up to about 0.5 percent of GDP. No single change exceeds 0.16 percent of GDP (positive or negative).

The clean energy credits reduce tax revenue by about 0.13 percent of GDP while IRS enforcement, net of the cost of new personnel, raises about 0.10 percent of GDP in new revenue. The corporate minimum tax raises about 0.05 percent of GDP in new revenue.

There are different ways to add these numbers, but ours are fairly consistent with an earlier estimate by Paul Krugman who wrote “the Biden agenda [including the infrastructure bill] will amount to around one-third of one percent of GDP. Massive it isn’t.”

This does not imply that “massive” or “big” is better. It’s often worse, partly because it can pre-empt better uses of government resources in later years. Much good legislation is incremental, and much bad legislation is big.

But if the IRA is not that big a fiscal deal relative to the much larger amount of money that government will raise and spend over the next decade, it does represent the type of fiscally balance policy making that Congress needs to make year after year to address new priorities.