The coronavirus recession has dealt a devastating blow to millions of US workers with consequences that could persist for years. As the public health crisis drags on, for many people temporary furloughs and reductions in hours are turning into permanent job losses and pay cuts that disproportionately affect low-wage workers.

Increasing income support through the tax code can ensure that low-wage workers are not left behind once the economy regains its footing and temporary relief programs end.

How are workers being affected by the COVID recession?

Thirty percent of all workers who were employed in February were out of work for part or all of March, April, and May. Women, workers with less than a bachelor’s degree, and Black and Hispanic workers experienced the highest levels of non-employment, and those categories of workers have experienced relatively slower recoveries.

Since an initial collapse, hours worked at small businesses have largely recovered but reached a plateau, with most lost hours attributable to closures or layoffs. And the longer the recession lasts, the more likely that layoffs initially recorded as temporary in survey data will become permanent. A University of Chicago study estimated that at least a third of pandemic-induced layoffs will be permanent, and in September, the number of permanent layoffs reached 3.8 million.

The overall jobs recovery has slowed since the summer, and there are still 10.7 million fewer jobs than there were in February. Those who eventually return to the workforce may do so at lower wages. Around 7 million workers who remained continuously employed have received nominal cuts to their base pay.

Employers are adapting to stay open

Businesses have been forced to rapidly change their practices to keep their doors open during the pandemic. One solution: substituting technology for workers. MIT economists David Autor and Elisabeth Reynolds call this process “automation forcing,” and they believe businesses will remember the lessons they learned about the potential for automation once the economy begins to recover.

Sylvain Leduc and Zheng Liu at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco analyzed a labor market model incorporating uncertainty about when workers can safely and productively return to their jobs. They found that employers currently have greater incentives to invest in technology than hire new workers.

Small businesses have been hit hardest in the pandemic. Yelp reported this month that 98,000 small businesses have closed permanently. Large businesses are now poised to claim a larger share of the labor market, at the expense of wage growth. There is evidence that large businesses are also more prone to invest in automation than small businesses.

The economic recovery needs to be inclusive

Low-wage workers experienced similar headwinds in previous economic recoveries, though on a smaller scale. After the past three recessions, overall employment recovered more slowly than economic output. Employees in jobs with routine tasks were replaced by technology, decreasing the demand for their employment, and putting downward pressure on their wages.

This process also exacerbates racial disparities. Black workers had the highest risk for job loss in past recessions. Most recently, their employment remained depressed for several years after the Great Recession ended.

As the coronavirus recession disproportionately hits workers in low-wage service professions, the recovery will likely be even more inequitable than in previous economic slumps. Some workers in these sectors have permanently lost their jobs, and many will face even more downward pressure on wages.

Tax policy can support wages

The long-term policy response to this challenge should certainly focus on recovering jobs and providing new employment opportunities, through funding job creation, and helping retrain workers for new jobs, and improving structural conditions for low-wage workers. Tax policy can also play a role by supplementing incomes for low-wage workers.

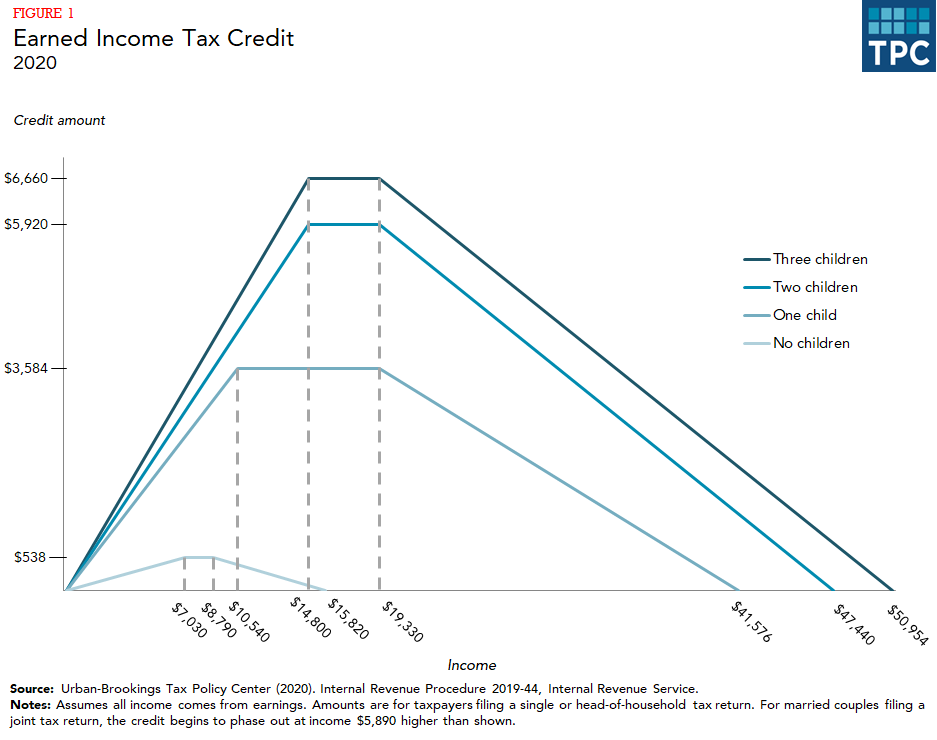

The tax code’s biggest support for low-income households is tied to work. The earned income tax credit (EITC) supplements labor earnings up to a maximum amount, when it begins to phase out. But it is designed primarily to help families with children. For instance, the maximum annual benefit for a family with three children is $6,660 while a household with no children at home can receive no more than $538.

The EITC could be modified in a variety of ways to provide expanded benefits to people with earnings. Several recent legislative proposals to expand the EITC, including Senator Sherrod Brown’s Working Families Tax Relief Act and Senator Kamala Harris’s LIFT Act, would implement these changes. TPC’s Len Burman has written about replacing the EITC with a large universal wage subsidy of 100 percent of the first $10,000 of earnings, available to all adult workers, whether or not they have children. The maximum earnings would grow over time as the economy expands.

Making the full credit available to all workers below a certain income level, while politically challenging, would enable the EITC to benefit workers who have been laid off and have trouble finding work in the longer term. Adopting this change temporarily, during recessions, could insulate workers somewhat from a loss in income. The full credit also could be made available to specific groups not currently in the paid labor force, such as low-income students and caregivers, as the Economic Security Project has proposed. In the short term, excluding unemployment benefits from adjusted gross income would help prevent reductions in EITC refunds for those who were unemployed this year.

Economic recovery will only be possible once the pandemic is brought under control with effective public health measures. But once it is, Congress should support low-wage workers experiencing lasting damage from the recession.