For cities, the COVID-19 economy is turning many winners into losers.

Before the global pandemic, economists and policymakers worried about the widening gap between cities that were “haves” and those that were “haves-nots.” While globally connected mega-cities prospered, the economies of small to mid-sized places—especially those without colleges and universities—were subject to the vagaries of weather, geography, and, well, luck.

But in the midst of COVID-19, previously ascendant college towns are now either virus hotspots or diminished versions of their former selves, missing out on students, football, and much needed revenue.

Meanwhile, big cities—especially tech and finance hubs—are bleeding service sector jobs as workers who can stay home do. This affects small businesses like coffee shops, restaurants, beauty salons, and basically any businesses requiring in-person interaction or rewarding service with a smile.

The pandemic and resulting recession could also mean a fundamental shift in local government finances. Already, revenue shortfalls and budget cuts are halting long-term infrastructure projects and forcing furloughs and layoffs. They may also require a re-examination of what is a financially successful city.

The city funding model may be broken

American cities are incredibly diverse—economically, demographically, and fiscally. But summary data help paint a picture of what a typical city’s revenue system looks like.

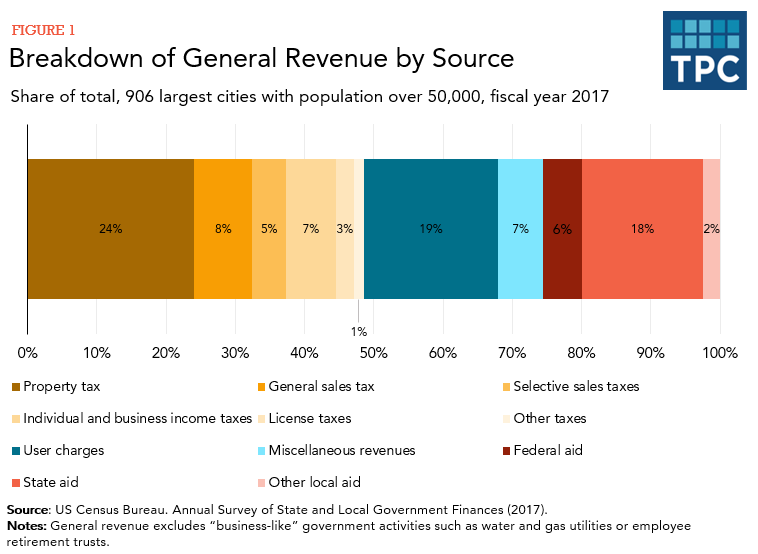

Among 906 cities with 50,000 or more residents, taxes provide roughly half of all general revenue, with half of that coming from property taxes. Fees and miscellaneous charges provide a quarter of general revenue and transfers (mostly from their states) provide another quarter.

But no city is a typical city. Each locality makes choices about its revenue system based on its economic mix and government structure.

Before COVID-19, cities able to diversify their revenue sources beyond property taxes—which are adored by economists but scorned by the public—were often seen as the winners. Those in states that granted access to local sales and income taxes were among the lucky ones.

But now that particular type of revenue diversity might spell trouble. Cities as a whole face COVID-19-induced revenue shortfalls of about 13 percent, but those that rely more on income and sales taxes could take an even bigger hit because these taxes track the economy more closely than property taxes.

Other taxes—particularly those related to leisure and hospitality—are even more vulnerable to pandemic-induced shortfalls. For example, hotel occupancy taxes have traditionally been a great way for cities to export tax burdens to tourists and other non-residents. Relying on these revenues is not possible now. In fact, hotel tax revenue fell 80 percent in New York City and by similar magnitudes in San Francisco and Los Angeles.

Fees and charges for services such as parking and business permits pose another set of risks.

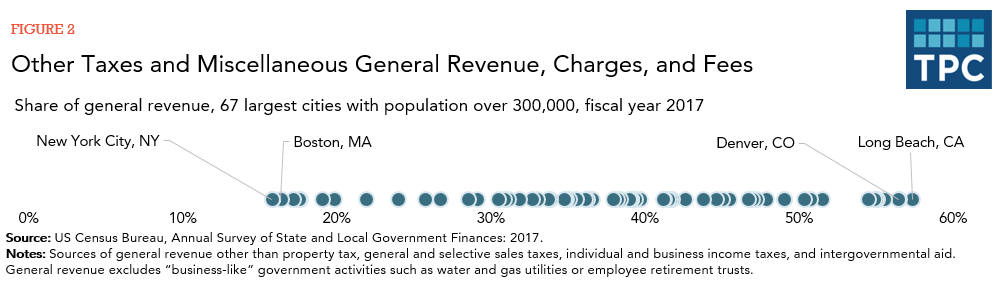

While these smaller revenue sources get less attention from many analysts than the “three-legged stool” of sales, property, and income taxes, together they account for roughly 40 percent of general revenue for the average big city (those with populations above 300,000) and much more in places such as Long Beach, Denver, Oakland, and Indianapolis.

Cities must closely examine their specific revenue systems

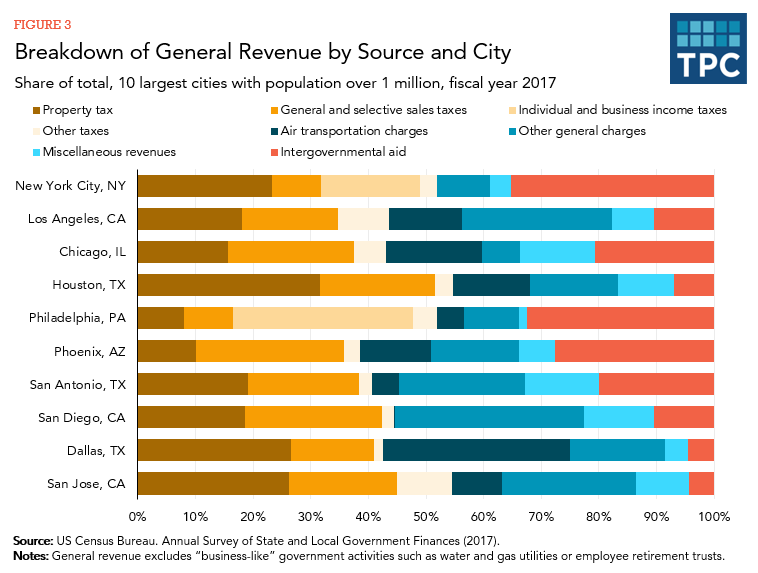

Given their diverse economies, revenue sources, and public health impacts of COVID-19, cities will need to respond differently to their pandemic-related revenue declines. Among the 10 largest cities, New York City and Philadelphia need to monitor job losses that will affect income tax revenue. In Phoenix and San Diego, where sales taxes are key components, falling consumption may matter more. In Chicago and Dallas, steep declines in air travel is slashing critical air transportation charges and related fees.

One thing hasn’t changed: the importance of support from states and Congress

Finally, let’s not forget about that last quarter of city revenue: state and federal aid.

Unfortunately, during the Great Recession, states imposed the biggest local aid cuts since 1960. States cut local aid for the same reason they cut other programs: because they must balance their budgets each year. And since cities also must balance their budgets, state budget cuts become city budget cuts, which often result in government job losses that can hurt services and slow economic recovery.

Because states and cities—unlike the federal government—can’t run deficits, the federal government often steps in to help during a recession. However, much of the federal COVID-19 aid passed so far is restricted to states or to direct costs associated with fighting the pandemic—and much of it expires in just 3 months.

The COVID-19 economy is forcing mayors to find creative ways to navigate rocky budgets, just as they did during the Great Recession. But we should remember that cities are not islands. They are intertwined with the nation’s economy and social fabric—so local budget struggles often have much wider implications.