House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) and President Joe Biden reached an agreement over the weekend to limit spending for a small fraction of the federal government for a couple of years. But it would not come close to materially reducing annual deficits or slowing the growth of the national debt, which the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) predicts is on pace to exceed $46 trillion by 2032.

The bill would cap spending discretionary spending (excluding entitlement programs such as Social Security and Medicare) through 2029. It would reduce that spending authority in fiscal year 2024 then increase it by 1 percent annually from 2025-2029. CBO estimates the plan would lower projected spending by about $64 billion in fiscal year 2024, or roughly 3.5 percent, and by about $107 billion in 2025.

The Loopholes

But there are two big caveats:

First, the agreement effectively is unenforceable after fiscal 2025. Any spending caps would have to be accepted by future congresses. And if history is any guide, they won’t be.

Second, many of the caps would be offset by a series of informal side deals, including some budget accounting gimmicks. Those agreements could mean non-entitlement domestic spending in 2024 would be only about 0.2 percent less than this year.

Why were these changes not included in the bill? Mostly so McCarthy could claim deeper spending reductions than he actually got. Since none of those informal agreements are in the actual legislation, they don’t show up in the official CBO score.

Inflating the savings is critical for McCarthy since the GOP’s fiscal demands have shrunk so dramatically in just five months. They started the year by vowing to balance the budget in a decade, which would have required lowering cumulative deficits by roughly $20 trillion over the period. By the time House Republicans passed their Limit, Save, Grow Act in April, they were aiming to cut deficits by about one-quarter of that, a total of about $4.8 trillion.

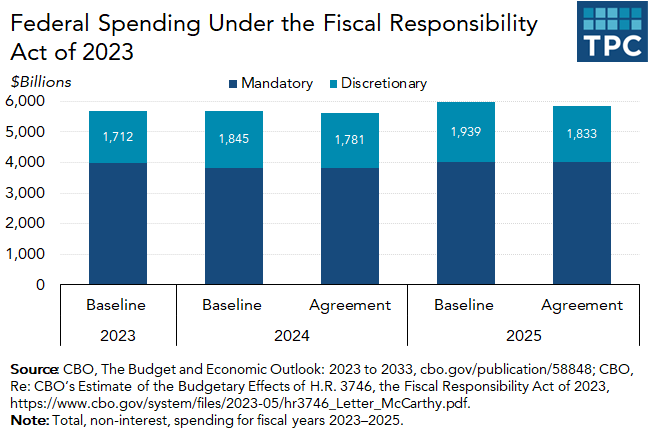

Now, McCarthy has agreed to cut planned spending by about $170 billion over the next two years, at least on paper. For reference, the federal government currently is on track to spend a total of $11.6 trillion in 2024 and 2025, excluding interest.

The result: A fiscal path that barely diverts from the one the nation already is on. It isn’t nothing. But it is far from the remaking of government that many in the GOP demanded.

A Pre-ordained Outcome

Here is what happens to total non-interest federal spending, according to CBO. But remember, it overstates actual savings.

This outcome has been ordained for weeks. In April, I predicted Congress would find a way to raise the debt limit without reducing the federal debt in any meaningful way.

Once Republicans agreed to take Social Security, Medicare, military spending, and veterans benefits off the table and refused to consider tax increases of any kind, they had no real way to achieve significant deficit reduction.

House Republicans left themselves with no choice but to focus all their cuts on only about one-seventh of non-interest federal spending. And many of those programs have powerful constituencies, even in the GOP caucus.

Rope-A-Dope

For their part, Biden and the Democrats made little attempt to push their own priorities in talks with McCarthy. Instead, Biden’s rope-a-dope tactics simply parried McCarthy’s best punches.

The GOP spends millions of dollars in negative ads and focuses much of its free media on attacking Joe Biden for his alleged age-related infirmities. But for a supposedly confused old guy, the president still plays the policy game awfully well.

Biden did concede a few issues. While he rejected a GOP push to toughen work requirements for Medicaid, he went along with some modest additional obligations for SNAP (food stamp) recipients. But also got a liberalization of other SNAP eligibility rules.

He agreed to shift about $28 billion in pandemic-related funding to other domestic spending. But chances are much of that COVID-19 money never would have been spent anyway.

The IRS Money

And he agreed to some reductions in projected IRS spending over the next decade, though exactly how that will play out much remains a mystery.

The bill itself scales back the Inflation Reduction Act’s (IRA) $80 billion bump in IRS spending by just $1.4 billion. But negotiators informally agreed to additional cuts of about $20 billion from the roughly $70 billion the IRS has not yet spent. The measure would “repurpose” about $10 billion in fiscal 2024, whatever that means, and shift $10 billion more to other domestic programs in fiscal 2025.

But keep in mind that the IRS has significant flexibility in when it spends the rest. So, at least in theory, it might be able to front-load some of its remaining $50 billion to the next couple of years and count on a future Democratic Congress and White House to restore the rest.

For all the bluster from the anti-government wing of the GOP and all the drama around the potential of a US government default, the Biden-McCarthy agreement changes almost nothing. Except, of course, it puts off the next debt limit drama for another two years.