Last week, I debated American Enterprise Institute resident scholar Aparna Mathur on the question of whether the corporate income tax rate cuts from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) have, as promised, increased business investment and grown worker wages. She and I agreed there is little evidence, so far. Aparna, more optimistic than I, argues the US may see benefits from the corporate rate cuts over time. But I am more skeptical. Congress enacted the cuts more than two years ago, without resulting investment or wage growth, or even green shoots.

The centerpiece of the TCJA was its cut in the maximum corporate income tax rate from 35% to 21%. The White House promised these cuts would add on average at least $4,000, or as much as $9,000, of extra pay annually for every US family. Although it sometimes promised this wage growth would begin “immediately,” a technical white paper cautioned it might take 3 to 5 years (or, perhaps, double that time). Other observers suggested the full effects on growth might take decades, not years.

Why would it take so long, if it happens at all? Several key, and uncertain, steps must occur before corporate tax cuts can translate into wage growth. First, corporations must attract and retain additional funds. Second, they must invest these funds in new plants, equipment, and processes. Third, the new investments must increase worker productivity. Finally, the workers must negotiate higher wages.

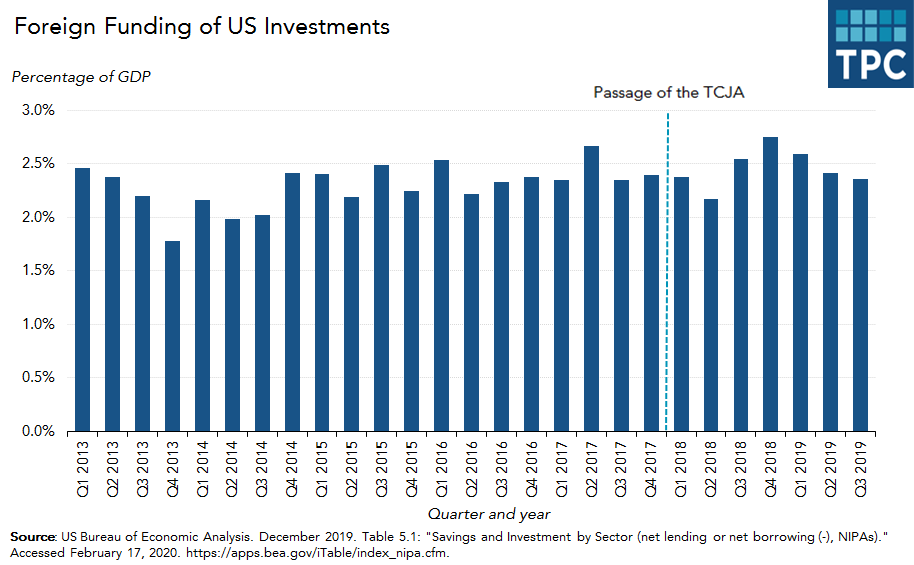

But are we on the path to those long run wage increases? Probably not. We still are not seeing any signs of the first two steps. First, we are not seeing US corporations attract and retain more funds. Foreign net investment into the US has been relatively flat.

And large corporations are using the vast majority of their tax savings to buy back their stock and pay dividends, rather than retain and invest in their businesses.

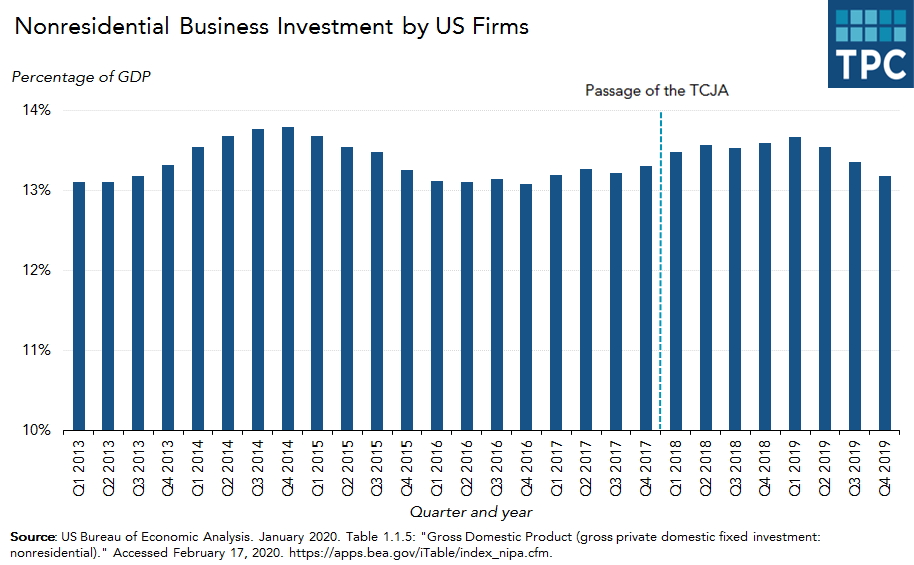

Second, US corporations are not increasing their investment in new plants, equipment, and processes. Indeed, firms reduced business investment the last three quarters of 2019.

The flurry of bonuses announced in the aftermath of the TCJA was largely attributable to one-time tax-rate arbitrage where firms used the opportunity to deduct that compensation at the higher pre-TCJA tax rate of 35 percent.

Who benefited from the corporate tax rate cuts? Shareholders in the short run, which could last many years. Under basic finance theory, an increase in the stream of after-tax profits expected in the future should, immediately, translate into higher stock prices.

And who are these winners? Foreign investors own roughly 35% of total US equity (public and private). And for US investors in equity, the top 1% own about 57% of shares while the bottom 90% own about 12%.

And who lost? Future generations, who eventually must repay the staggering US debt. The TCJA will add almost $2 trillion to nation’s nearly $18 trillion public debt over 10 years, of which about $1.4 trillion was attributable to corporate income tax rate cuts.

So, what did the TCJA’s corporate tax rate cuts bring us? Tax cuts for shareholders—who tend to be rich, including a sizable block of foreigners—and, eventually, tax increases or spending cuts for the rest of us.