This year residents of the District of Columbia are getting the last tranche of a phased-in tax cut that was enacted in 2014. But because the relief was based on linking key provisions of the District’s income tax to the federal code, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) has scrambled the expected tax changes for District residents.

Post TCJA, some households are receiving a bigger-than-expected District tax cut and others are getting a smaller reduction. In fact, depending on family size and whether you’re a half-full or half-empty type, you could consider the 2018 tax cut a tax hike.

The situation highlights the benefits and burdens of tax conformity, and shows how hard it is for a jurisdiction to change course once it hitches its tax system to the federal government.

The story started four years ago when the Council of the District of Columbia passed sweeping tax reform based on the recommendations of the DC Tax Revision Commission. Among many other changes, the District adopted the federal government’s more generous standard deductions and personal exemption.

I was a staffer on the Commission, and we saw this as a twofer: conforming to federal law simplified the District’s income taxes for taxpayers and provided tax relief to low- and middle-income residents. At the time, the District’s standard deduction was $4,100 for all filers, so conformity with the federal rules increased it by roughly $2,000 for single filers and $8,000 for married couples. It also boosted the District’s personal exemption from $1,675 to roughly $4,000.

However, some of the tax cuts were phased in over a period of years, dependent on triggers. Thus, in 2017, the District’s standard deduction was $5,650 for singles and $10,275 married couples and its personal exemption was $1,775—higher than the 2014 levels but still below the federal levels.

In February 2017, the District’s fiscal situation was so good that the city pulled all of the remaining triggers. That meant the District would fully adopt the federal standard deduction ($6,500 for singles and $13,000 for married couples) and personal exemption ($4,150) in 2018.

Of course, in 2014 the District could never have imagined Congress would pass a major tax overhaul that nearly doubled the federal standard deduction and eliminated personal exemptions. But because of newly established conformity, when the TCJA passed in December 2017 the District’s standard deductions and personal exemptions changed, too.

This significantly altered the District’s scheduled 2018 tax relief. Many families with multiple children could now owe more in District taxes than they would have pre-TCJA because while they are getting a bigger standard deduction they are losing personal exemptions. (This did not happen nearly as much at the federal level because Congress also increased the maximum child tax credit. The District does not have a child tax credit.)

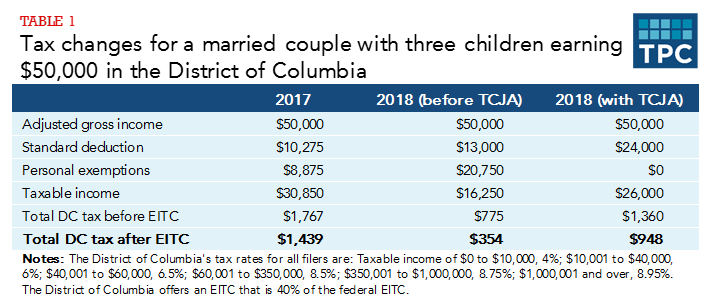

Consider a hypothetical married couple with three children earning $50,000 in the District (table 1). They owed roughly $1,450 in District income taxes in 2017, assuming they were eligible for the District’s earned income tax credit (EITC). If the TCJA had never happened, their District income tax bill would have fallen to about $350 this year. But now they’ll pay closer to $950.

Did this family get a $500 tax cut or a $600 tax increase?

The same family earning $30,000 will get a larger tax refund (because of the District’s refundable EITC) in 2018 than 2017, but the refund is about $250 less with the TCJA replacing the old federal rules. If this family earns $80,000, their 2018 tax cut is about $600 lower than it would have been absent the shift in federal law.

All these families pay less tax in 2018. But are they winners or losers?

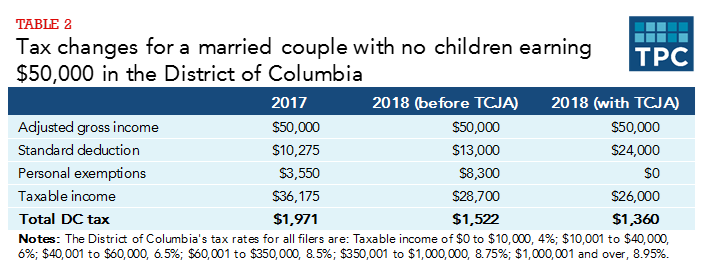

One sure winner: District taxpayers without children. A childless couple earning $50,000 was set to get a $400 District tax cut under the old rules (table 2). But after TCJA, they’ll get a $600 tax cut. A single filer with no children and the same income gets $100 more after TCJA. For childless filers, the larger standard deduction is more valuable than the lost personal exemptions.

If the District considers this a problem, it could follow Idaho’s lead and create a child tax credit that fills in the gap for families with children as it does at the federal level. Or the District could decouple from the federal rules and set its standard deduction and personal exemptions at the old federal levels. In fact, the District did just this with its estate tax by decoupling from the new, higher exemption created by the TCJA and setting its own level, reversing the conformity established in 2014.

But decoupling or creating a child tax credit takes more legislative action and has revenue costs. This is in part why Idaho so far is the only state to make a change. Most, like Utah, have not acted.

And will District taxpayers even notice these odd conformity changes? After all, those affected are all still paying lower District income taxes next year. That’s a better deal than in other conformity states, such as Colorado, Minnesota, and Utah where many large families could pay more (if the states don’t act).

So far, neither the mayor nor Council have proposed individual income tax changes in this year’s budget. They both focused mostly on something far more visible to their constituents: funding Metro.