President Trump was afraid to tackle the dominant set of spending and tax issues facing the federal government. Ditto, so far, for President Biden. Under current law, the Social Security and Medicare trust funds that pay out crucial benefits to retirees will go insolvent by roughly 2034 and 2026, respectively, triggering large mandatory benefit cuts. Meanwhile, the gap between scheduled benefits and taxes paid directly to cover the cost of these programs continues to grow.

Every elected official knows this. And no one expects benefits for existing retirees suddenly to be cut in 2034 or 2026. But fixing the problem requires some combination of tax hikes and reduction in the rate of growth of future benefits, neither of which pleases Congress’ or presidents’ political palates for admitting to having made promises that couldn’t be kept.

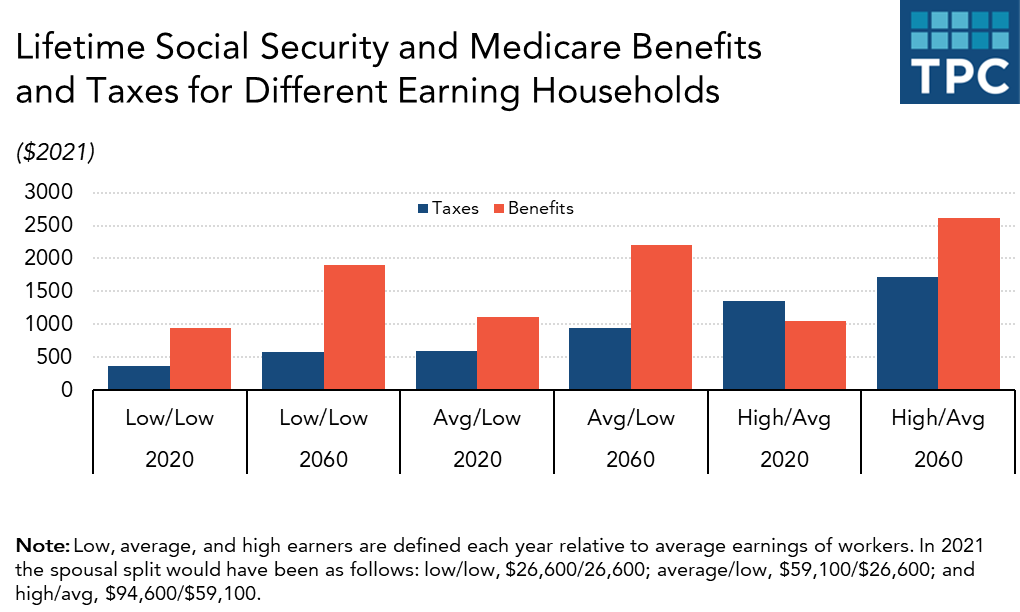

Politics differs from economics. The estimated total benefits retired couples would receive under current law grows so much that Congress has a fair degree of freedom to right-size both programs, while still providing significantly higher benefits for future retirees. The latest edition of Social Security & Medicare Lifetime Benefits and Taxes illustrates the combined benefits currently scheduled for different hypothetical households with retirement dates ranging from 1960 all the way out to 2060. At the same time, those benefits far outstrip the amount of Social Security and Medicare taxes and fees paid by almost all recipients.

First let’s consider a married couple who two low earners making significantly less than the average worker each year (the equivalent of $26,600 each in 2021 dollars). Those who retired in 2020 would have paid $364,000 in Social Security and Medicare taxes and receive $940,000 in benefits (net of any fees). Meanwhile, a millennial couple earning that same amount and retiring in 2060 would pay in $584,000 in taxes and get $1.9 million in benefits, more than double their 2020 retiree counterparts.

The story is similar higher up the income ladder. A married couple with one high wage earner and one average wage earner (a combined $153,700 in 2021 dollars) retiring in 2060 would pay in $1.7 million in taxes and get $2.6 million in benefits.

Social Security reform is often painted as a tool to take away benefits from vulnerable seniors. But reform essentially means addressing two issues: at what rate to improve lives for seniors, even if average benefits rise more slowly than currently scheduled; and how much more to collect taxes mainly from those of working age, even if at higher rates than currently scheduled. That leaves a lot of room for improving the lives of the most vulnerable seniors. Among the many possibilities at many different benefit growth rates are: eliminating poverty among the elderly and disabled; rejiggering payments so that a larger share is paid in later, less healthy, years when long-term care becomes more likely; addressing the ways that Social Security disproportionately favors wealthier retirees when it provides more years of retirement benefits as people live longer; and cutting health costs in ways that allow more cash benefits to be received by beneficiaries.

Don’t worry, millennials and other future generations of retirees. Almost without a doubt you’ll get many more retirement benefits than counterparts from earlier generations.

A well-designed reform could not only secure the future financing of these programs but also free up resources for other priorities. For instance, by allowing those Social Security and Medicare deficits to grow substantially, President Biden had almost no way to capture the increased government revenues accompanying economic growth to support additional efforts for children and the environment.

I’m not naïve. The political sniping surrounding the Medicare and Social Security reform debates won’t go away anytime soon. But we should view the necessary reforms of these systems as an opportunity to both make these programs and the federal budget sustainable and improve lives for the most vulnerable of seniors. Those near to or in retirement aren’t going to pay much more one way or the other.

Don’t just take my word for it. Instead, examine the lifetime benefits and taxes scheduled for future workers and retirees. Then see if you don’t agree that we can make sustainable choices that would do better for both groups than staying our current path.